The word on the street these days is Design. It comes up in terms like ‘design thinking’ and ‘design process’. Educators are increasingly being urged to use design in their professional practice and to teach design skills to their students. But what is design? What is its role in education in the 21st century? And finally, how are these ideas related to STEAM and Makerspaces more broadly?

What is ‘design’?

The word ‘design’ exists as a noun and a verb, and has been used in a wide variety of contexts, leading to confusion as to its meanings. When we ask kids in elementary classrooms to tell us what design is, most of them say “to decorate, to make something look nice, like a room makeover”. I would imagine many adults have the same definition in mind as well. Oxford Dictionaries offers the following neutral definition:

de·sign /dəˈzīn/…1.1. Do or plan (something) with a specific purpose or intention in mind.

I like this definition because of its clear insitence on both planning and action, and its lack of reference to context. Sure, you can design a room to make it look pretty, if that is your intention, but the design act can be deployed in a variety of contexts of widening scope, most of which have little or nothing to do with making something look pretty.

Todd Olson of The Design Innovator offers up this more detailed definition of design as a discipline:

design (verb), as a discipline: plan the creation of a product or service with the intention of improving human experience with respect to a specified problem.

The plot thickens. Now we are adding shading and detail to the acts of planning and action found in the Oxford definition. Two new elements emerge: 1) design occurs in answer to a problem and 2) with the goal of improving the experience for the user.

Wikipedia lets us glimpse the scope of design as a discipline across contexts:

Design is the creation of a plan or convention for the construction of an object, system or measurable human interaction (as in architectural blueprints, engineering drawings, business processes, circuit diagrams, and sewing patterns). Design has different connotations in different fields … In some cases, the direct construction of an object (as in pottery, engineering, management, coding, and graphic design) is also considered to use design thinking.

image from Blueprint – copyright cleared

The design process

Turns out that humans are designers. It used to be that disciplines wanted to be unique and bespoke, with their own ways of approaching the thorny problems of their respective fields. As disciplines emerged, and as information didn’t flow as freely as it does today, idiosyncratic language prevented us from seeing the patterns that unite all disciplines involved with the construction of objects, systems or measurable human interaction – in short, the patterns that unite all of human activity.

Enter the design process. Say you’re a human in the Stone Age. You need to kill and skin an animal more efficiently (problem). Ok, you can use sticks that you sharpen by rubbing on rocks, or rocks themselves, especially those sharp ones you found the other day (brainstorm). Oh, there’s an animal now, let’s try the sharp stick that we have here (prototype). Ok, it works, but it broke in half because of the impact, so what if we attach this here pointy rock we found with some vines (make)? Hmmm, that was good, but the rock is getting dull already, so how are we going to make it sharper (reflect)? We need to sharpen this rock and see how that will work (iterate). Sounds familiar? We’ve been doing it since the dawn of humankind. No wonder it seems so obvious.

Design for educators vs teaching design to students

Here is where things get a bit meta, to borrow a colloquial term. Teachers can be designers of educational experiences themselves, as the classroom professionals that they are. And, they can also teach the design process to students. These are two different acts – and I’ll tackle teacher-as-designer in another post. Let’s focus on students for now.

Why teach the design process to students?

For the most part, education has shifted from ‘knowing about’ something to engaging in action in a specific field. The Quebec Education Program emerged in direct response to this educational climate by rooting its subject area programmes in competencies – i.e. what a learner can do with knowledge and skills in a given context at various points in time. ‘Doing’ implies engaging in one of the many processes we leverage to help us navigate complexity: a research process, a writing process, a problem-solving process, a creative process, a project process, a design process. The design process, like the other processes listed, has the benefit of being able to cross disciplinary boundaries, preparing students for adult life of their choosing. In the Science and Technology programme, the Cycle 1 Secondary text references the Technological Process, which can be said to fit under the umbrella of the design process.

The design process also allows learned to develop the Cross Curricular Competencies (that bête noire of the QEP, but very dear to my own heart), or those 6 C’s of Deep Learning that Michael Fullan talks about, or even 21st Century Skills that we see mentioned in the media. No matter by what name they are called, we all agree that they are the cornerstone of preparing young people for active participation in the world.

Makerspaces and design thinking

It’s no secret that here at LEARN we are big proponents of Making in schools – of getting students’ heads, hearts AND hands right into their learning. The educators with whom we have been privileged to collaborate, have highlighted for us how important it is to have structures within which the chaos of making finds meaning. Make no mistake, when you open up your classroom to Making or bring your students to a dedicated Makerspace, it can get pretty chaotic. Sure, kids are engaged for the most part, and most of them are working on something, but what are they learning? Are they all learning the same thing? (Is that important? A question for another post, perhaps).

The design process brings order to what can otherwise be a chaotic learning environment. It provides structure for the unstructured and the ambiguous. For some students, less interested in tinkering and making for its own sake, it can also provide a purpose, as they wrestle with thorny problems and come up with practical solutions to prototype in the Makerspace.

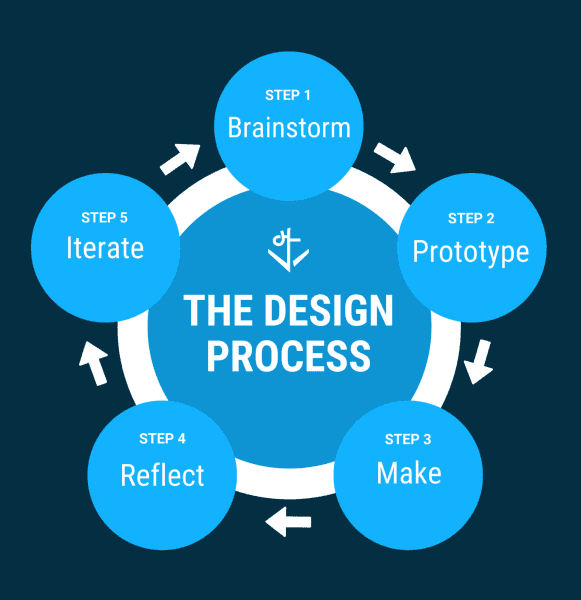

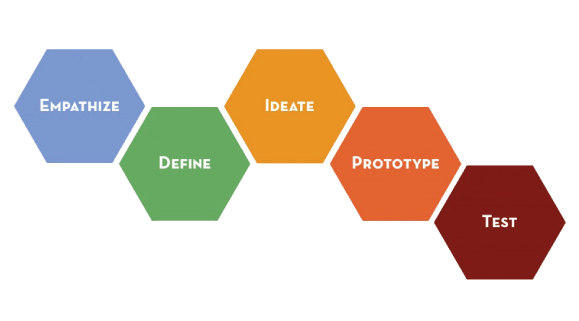

Visuals of the design process abound and you can pretty much choose one that appeals to you and work with that one. The key is consistency in terms of visuals and vocabulary – your students should have one process to work with, and their student learning tools should match the visual you use. If you see after some time that the visual you have chosen doesn’t suit your evolving needs – change it! Find a new one, or make your own with something like Piktochart.

Diana Rendina from Renovated Learning uses this process with her students – and makes her student tool available for all as a Google Doc:

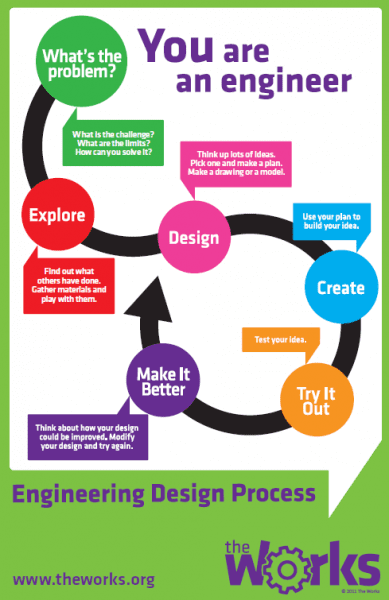

Here are some other design process visuals

This one above from Stanford’s d.school initiative includes the step Empathize, which allows younger learners not used to thinking about the needs of others to put themselves in someone else’s shoes to see the world through their eyes. Heck, apparently, its not just kids who are not used to thinking about the needs of others since Todd Olson of The Design Innovator writes “Arguably the most important new line of thinking is around the concept of user-centeredness, which is at the heart of the design thinking movement.” (emphasis mine).

However, I think that if you are just starting out, simpler is better, and you can always add on.

We talk a great deal about schools needing to prepare children for their future, and not ours. We’re not always sure how to go about it, either. But one thing is clear: to teach students how to work with the design process in whatever context, is to give them the gift of navigating those problems that we cannot yet even name.

(c) Todd Berman

Reflective Question: Is Design Thinking or processes associated with design on your professional radar for this year? How does it fit with some of your current practices, whether as consultant or teacher?

*******

Wiggins and McTighe (2006). Understanding by Design. Pearson: Merrill Prentice Hall. p. 24. ISBN 0-13-195084-3.

Stanford’s Design Process for Kids: Teaching Big Picture Problem Solving – http://www.ideaco.org/2013/07/standfords-design-process-for-kids-teaching-big-picture-problem-solving/

d.school at Stanford – K-12 Lab https://dschool.stanford.edu/programs/k12-lab-network