It was the spring of 1999. Heading out the door of the inner city elementary school where both my husband and I were working, I bombarded him (as I always did) with a series of mini episodes of what had gone on in my grade 5/6 classroom that day; snippets of exchanges with the students, jokes and fun mixed with a smattering of “a-ha!” moments that were always to be celebrated. He smiled, half listening; clearly deep in thoughts of his own. Earlier that year, Christopher had developed curriculum that integrated, among other subject areas, literacy, technology and sports in a way that was not only improving the students’ reading and writing abilities but was so engaging that it inspired a targeted group of at-risk kids; it built their self esteem and commitment to continue along the path of learning.

It was the spring of 1999. Heading out the door of the inner city elementary school where both my husband and I were working, I bombarded him (as I always did) with a series of mini episodes of what had gone on in my grade 5/6 classroom that day; snippets of exchanges with the students, jokes and fun mixed with a smattering of “a-ha!” moments that were always to be celebrated. He smiled, half listening; clearly deep in thoughts of his own. Earlier that year, Christopher had developed curriculum that integrated, among other subject areas, literacy, technology and sports in a way that was not only improving the students’ reading and writing abilities but was so engaging that it inspired a targeted group of at-risk kids; it built their self esteem and commitment to continue along the path of learning.

News of this dynamic teaching and learning curriculum had reached the ears of the ministry and he was now going to be the focus of a documentary that would clearly demonstrate for the rest of the province the QEP (our new Quebec Education Program) in action, lived out with an at-risk population. Our principal was delighted. I was thrilled and Christopher was overwhelmed to be recognized in this way. I continued bubbling with what all this meant. He was going to be the face of the QEP. How wonderful!!

As we buckled up our seat belts, Christopher turned to me and spoke for the first time since we had walked out the school door, “Mel. What the hell is the QEP?”

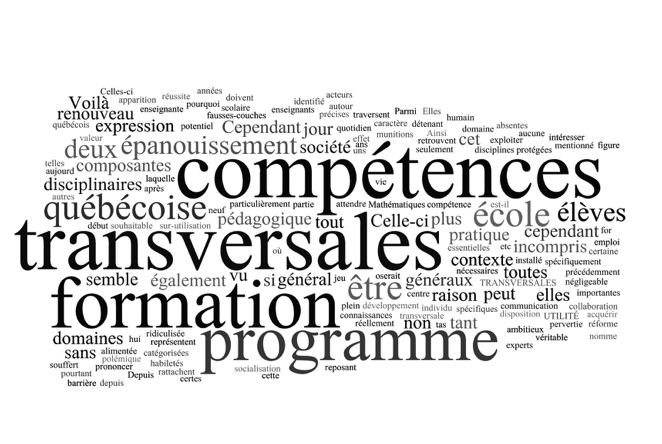

I remember laughing out loud. As we had just recently returned from living in the Cree community of Mistissini for over a year and a half, we had missed all the commotion and build up of the soon to be implemented Quebec Education Program. This didn’t seem to matter though because as it turned out, the philosophy and ideology behind this “Reform” was based on what was occurring in our classrooms already. It emphasized the importance of knowledge acquisition, critical thinking, inquiry-based learning, collaboration, cross-curricular learning, and democratic living.

As I read more deeply the numerous documents produced by The Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport (MELS), it quickly became obvious to me, that there were many elements of the QEP being implemented that would profoundly alter the teaching and learning in Québec schools in my opinion for the better. For one thing, it accorded greater recognition to the professional, teaching methods, and choice of methods of evaluation of students’ learning (MELS, 2005, p. 8). As well, it allowed teachers to choose their pedagogical approaches according to the situation, the nature of the learning to be accomplished or the students’ characteristics. This could be managed by lecturing, explicit instruction, project-based teaching, inductive teaching, strategic instruction, cooperative learning or any other method the teacher deemed appropriate. (MELS, 2005).

For the first time in my career, this progressive ideological shift was putting the teachers in control of their own classrooms. It was affording them the opportunity to be autonomous professionals. Who knew better than the teacher him/herself what was best for their students?

The role of teachers became one of supporting students in their learning process, helping them structure and build on their knowledge, rather than being the expert who transmits information. Students were encouraged to participate in constructing their knowledge. “Instead of mostly listening, they are actively engaged in processing the information so as to transform it into knowledge and competencies.” They may even act as experts in cases where they have specific knowledge. (MELS, 2001, p. 2) In this “innovative” way of looking at teaching and learning, of primary concern is that students transform information into viable and transferable knowledge “The elements of knowledge students develop are tools that should help them understand and take action in the world,”(MELS, 2001, p.1). Learning does not simply take place in the classroom. It does not begin and end with the ringing of the bells, “…the reform aims for learning that takes place in school to be transferable, i.e. to serve a purpose other than just school.” (MELS, 2001, p. 2).

It goes without saying that having teachers take into consideration a program that implies a major adaptation on the pedagogic level has been anything but easy. We must be patient and keep in mind that changes of such magnitude cannot be implemented into a machine as vast as the educational network over a short period of time or without experiencing some difficulties. Many have questioned whether or not the disruption and disorder brought about by this shift has been worth it. I am reminded of Margaret Meek, who in referring to Freire writes “and He wants us to consider the worth of an idea by asking what difference it would make” (Freire & Macedo, 1987, p. xxvii). When looking at the pedagogic basis and the potential outcomes for students being educated in this way, I think it will make an enormous difference in the way that teachers and students come together to share in the learning process, to dialogue and to empower each other and themselves. So my answer to the question “Is it worth it?” rings out loud and clear “Yes, it is most definitely worth it!”

Fast forward almost ten years.

In the fall of 2008, I had the privilege of taking a graduate course with a critical pedagogue who had come to McGill. It was a time in my life that I will never forget. He would sit at the head of the semi-circle, clad in black jeans and a black t-shirt and he would talk to us…no, tell us stories is probably more accurate. One thing was clear, he was not impressed with the manner in which schools operated and the overtly discriminatory practices that occurred throughout our North American system. He spoke of the issues of a standardized curriculum where so many students were simply left out of the equation due to their gender, race, ethnicity, religion, orientation or social status and of teachers who were forced by the government to push a curriculum that they knew would fail so many of their students.

One evening, half way through the semester, a number of my peers, who were not from Québec, joined in on the conversation, angrily claiming that they understood exactly what this critical pedagogue was talking about. They ranted openly about the problems we had here in Québec as our curriculum was without question as standardized as others throughout the rest of Canada and the United States. I was shocked by their statements. How could anyone who had read this document claim that it was standardized when the very underlying philosophy promoted teacher professionalism and autonomy by advocating self-selection of pedagogy, resources, methods and evaluation? It became clear to me that they hadn’t read the document. And when I asked this question outright, the answer that echoed around the room was that indeed they hadn’t.

Months later, I was sitting in his home, when his son, who was a high school ELA teacher, walked into the room holding onto his laptop. His eyes were wide in disbelief as he scanned the screen. Looking up from his reading of The Québec Education Program he exclaimed in disbelief “Hey, did you know that Freire is quoted in here?” I chuckled out loud. Here was the son of two of the most prevalent minds in critical pedagogy, not to mention a successful English Secondary School teacher, and he was just now realizing that the curriculum he was teaching was based on the theories and ideology of Paulo Freire.

What struck home at this point was that here was a curriculum document that was almost ten years into implementation and it was still being referred to as “The Reform” or even “New” and added to that was the reality that so many in the field of education, from classroom teachers to critical pedagogues, had never taken the time to sit down and read it through in order to understand the freedom it offered along with the respect of viewing teachers as professionals.

In an era of “No Child Left Behind” standardized curriculum throughout the United States and a thrust for “back to the basics” in most of North America, we in Québec have been given the opportunity through the Québec Education Program (QEP) to teach a completely unstandardized curriculum. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Freireian based model of critical pedagogy underlying the English Language Arts literacy program. It was designed to promote the development of literacy as both an individual achievement and a social skill as well as “the development of a confident learner who finds in language, discourse and genre a means of coming to terms with ideas and experiences, and a medium for communicating with others and learning across the curriculum” (MELS, 2008, p.6)

A few weeks ago, I had the privilege of presenting our Quebec curriculum at a gathering of academics and teachers at The International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry, held at the University of Illinois. The dialogue that followed my presentation was a mix of shock and confusion. There was an overwhelming buzz of excitement and genuine interest in the curriculum that is found here in Quebec. No one could believe that our teachers were awarded such autonomy and self-determination in deciding the best suited pedagogy, resources and teaching strategies to ensure their particular group of students be able to meet the outcomes at the end of a cycle. They cringed as they compared this to the system under which they were forced to work; teach to the test, no time for the rest. There simply wasn’t a mechanism put in place that would permit them to look at their students as individuals, to allow for a variety of perspectives or opinions, or for that matter to even ask the students what they wanted or cared to learn. They were envious of what we had in place and I truly began to understand once again how lucky we were.

So as the end of year stress begins to build. I think it is important to remember that we have been given a very precious gift…the acknowledgment that we are capable and competent to accomplish great learning alongside our students. And to think that we have a government document that supports this, reassures me time and again. When the pressure starts to become too much, I simply have to open up the QEP and read “More than ever, teaching requires autonomy, creativity and professional expertise.” (MELS, 2001, p.5) If you ask me, that’s not a bad thing at all to have to work towards!

For further reading:

Freire, P. & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the Word and the World. London: Routledge.

Québec. Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport. The Education Reform: The Changes Under Way. Bibliothèque nationale du Québec, 2005. Retrieved from http://www.mels.gouv.qc.ca/lancement/Renouveau_ped/452771.pdf

Québec. Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport. (2007). Provincewide panorama – Literacy in Québec in 2003. Info Adult-Ed. Vol. 4, Issue 1, January 2001. Retrieved from http://www.mels.gouv.qc.ca/_information_continue/info/index_en.asp?page=article6

Québec. Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport. Québec Education Program, Preschool Education, Elementary Education. Bibliothèque nationale du Québec, 2001. Retrieved from http://www.mels.gouv.qc.ca/dfgj/dp/programme_de_formation/primaire/pdf/educprg2001/educprg2001.pdf

Québec. Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport. Québec Education Program, Secondary School Education, Cycle Two. Bibliothèque nationale du Québec, 2008. Retrieved from http://www.mels.gouv.qc.ca/sections/programmeformation/secondaire2/medias/en/5b_QEP_SELA.pdf

We have a great QEP and we need to be sure that it stays a great QEP. Like you Mel, I especially appreciate what we have when I go to conferences abroad. That being said, I always learn a lot too.

This may be true in elementary schools, but certainly not in high school. Especially at the Seconday 4 level where our students are subjected to several MELS uniform exams and the dreaded moderation. We are right back where we were 10 years ago, teaching to an exam.

Yes, it is true that the uniform exams at the Sec. level have gone a long way to making teachers go back thinking that they should teach to the test. But aren’t those exams different from what they were ten years ago?