In my previous post on Action Research in the classroom, I wrote about the idea of action research as a form of self-directed professional learning. I think that we learn to be better teachers by asking questions about issues we have in our practice, and then taking steps to answer these questions. The issues we have are unique to us, unique to our way of seeing the world and our particular school and class situation. Our unique preoccupations lead us to reflect and ask questions about how we might improve our practice. Good action research questions a) come from our own practice, b) are in our sphere of influence and c) assume that we are where we are. The question, of course, is just the beginning…

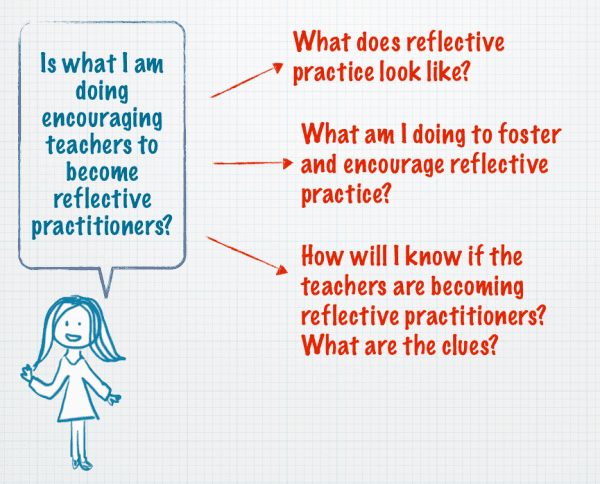

In one of the many lives I lead, I work with dance teachers on their practice as art educators. I run a teacher development series that takes place every six weeks throughout the year. It is a very participatory series, with discussions and sharing of thoughts and ideas about teaching dance to adult non-dancers (although… we believe that everyone is a dancer). I am a big proponent of reflective practice, an process articulated by Donald Schön in his book Educating the Reflective Practitioner. The main question I have about my own practice is “Is what I am doing encouraging the teachers to become reflective practitioners?”. I started by unpacking the question into several subquestions:

Answering some of these questions allows me to see what evidence I need to answer my main question. If I have a clear picture of what I am looking for in a reflective practitioner, I am more likely to know it when I see it. If I know what it looks like, then I am able to figure out what I need to do to find out if it is happening. This leads me to the very important step of data collection. Hopefully, as you read this, you have your own question in mind. Having your own question, no matter how embryonic or hazy, will allow you to see how different types or sources of data can be used to answer it.

I think of data collection like being at an all-you-can-eat buffet. You have many options, but not all of them are going to suit your needs or your tastes. Also, as we are naturally drawn to some food over others, so too, are we naturally drawn to some ways of collecting evidence over others.

The options

The evidence buffet is long and loaded with steaming dishes of data. On one side you have those sources which are primarily words and called qualitative or narrative. The other side is heavy with data which can be counted, tallied or rated. This is called quantitative data.

The important thing is not to get bogged down in the array of choices available, but to select sources of data that fit a few key criteria.

1. The data must work to help you answer your question

Let’s return to my main question: “Is what I am doing actually encouraging the teachers to become reflective practitioners?”. Although I have a fancy new still camera and enjoy taking pictures, I am not sure that taking photographs would go towards answering that particular question. I would probably lean toward interviews, documents from teacher development sessions, along with activity on our private Facebook group. In other words, there has to be a match between what you hope to learn and the data you decide to collect.

2. Several sources are better than one

One is the loneliest number, in love and in action research. Using more than one source of data allows you to be more certain that your conclusions will be accurate and will adequately reflect the reality you are studying. Researchers ideally aim for three sources of data. Three, unlike one, is a magic number.

3. Collecting data should be a natural part of your day

You are a teacher first. The best sources of data are those that occur naturally or can be built into the normal activities of the classroom. Snapping a photograph of your students during a Daily Five session, or making copies of key reflections for tracking are examples of data collection that do not interfere significantly with your work day. Another example is previously existing data, from earlier in the year or from previous years. In short, data collection should not take up too much of your time.

4. The data collection phase needs an end date

Action research is most manageable when finite, when it has a clear beginning and end. This does not mean that you cannot engage in research all the time. It just means that having a fixed timeline will help you either answer or refine your original question and lead to results. It will also help you plan out key moments of data collection – for example, collecting reflections at the beginning of every month to track their depth and quality.

You in your research

There is a belief shared by some that research should be free of bias and that researchers should strive for emotional and intellectual distance from that which is under study. Fortunately, the opposing point of view exists as well! I think that you should not divorce your values, beliefs and insights from your research. Your unique viewpoint and your privileged status as teacher-researcher is what will give your research an unmistakable ring of truth. Remaining aware of and communicating what you believe to be true about education and about learning, will also help you frame future research and find communities of like-minded educators. Like this one! Write and tell me how it’s going – I would love to hear from you.

Sylwia Bielec

***

http://actionresearch.asb-wiki.wikispaces.net/Data+Collection

Glesne, Corrine. (2010). Becoming Qualitative Researchers: An Introduction, 4th ed. Addison Wesley Longman Inc. New York, NY. 336 pages. Available from booksellers, e.g. Amazon

Schön, Donald. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Towards a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. Jossey-Bass. 376 pages. Available from booksellers, e.g. Amazon

As a teacher-researcher I have the unique opportunity to know the individuals within my class. I learn the personalities, dreams, and interests of my students. I learn how to motivate and reach them.

I have the opportunity to see how my students react to different situations. I listen to them and I hear them. They are so proud to share and to be listened to. They are not a number or a statistic to me. They are special people.

A photograph is an excellent way to capture a moment within a class. My students are used to the camera so the pictures are authentic. They do not pose when they see the camera. They continue to go about their routine.

A short video recording can capture body language and expression. It may remind me of an activity that was successful or of something I might need to modify to improve an activity’s success.

I find ePEARL (an Electronic Portfolio Encouraging Active Reflective Learning) to be a great way to monitor my students’ progress. I am teaching first grade and I am always impressed when I listen to a response to a story or to a reflection on a story they read. It tells me so much more than seeing which option they choose to color: a happy, neutral, or sad face. If my students write a reflection or response they are still in the beginning stages of writing. They are learning how to form letters correctly, provide spaces between words, start their sentence with capital letters, end their sentences with punctuation and they try to spell closely enough so that others can read and understand what they wrote. Often they have difficulty focusing on a response or a reflection when they are taking these things into consideration. The recorder is short and to the point. In one minute they successfully express themselves and they take pride in hearing themselves when they play it back. They may even modify their recording to add more incite because after listening to their own recording they may think of one other thing they wanted to mention.

Portfolios allow me to see areas that my students are improving in and areas where they need to concentrate. When my class works on an assignment that my previous year’s students also accomplished, I am able to make general observations about where this group is at in comparison.

In conclusion, I feel reassured knowing that sometimes a photograph is the best tool to use and it only takes a split second to create. I agree that one form of data collection is not enough. And non-biased forms of research are important but, in my opinion, the data collected is not more relevant or important than the research that takes place in the classrooms of teachers each day.