L’original de ce texte à été publié en français le lundi, 3 octobre, 2011.

This is the English version.

The current adoption of IWBs (Interactive White Boards)by educators, coupled with the growing popularity of tablet computers in schools brings up an oft discussed and sometimes hotly debated notion: interactivity. So ubiquitous is the idea of interactivity, and so apparently clear its benefits, that when asked about the inherent advantages of IWBs or tablet computers, the automatic response is usually “Why, it’s interactive!”

But what do we really mean when we call something ‘interactive’? Are the educational acts described when we discuss IBWs and other technological devices really an example of interactivity? Are there any real advantages to structuring learning that is interactive?

“This tool is interactive!”

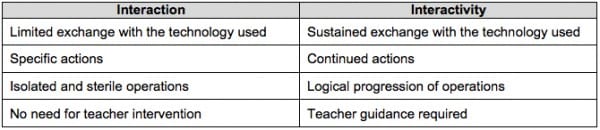

Often, listening to some teachers talk about their device of choice is enough to understand what they mean when they call it ‘interactive’. He or she might say that students can get up and go to the board to execute a simple operation (ex.: pressing on a specific section of the IBW to answer a multiple choice question). Interactivity, in this case, is limited to the fact that the student has manipulated the board in a way not much different from the way he or she would work with a good ol’ fashioned exercise book. But is this really a true description of interactivity with the technological tool of choice, or are we really talking about interaction?

Interaction and interactivity

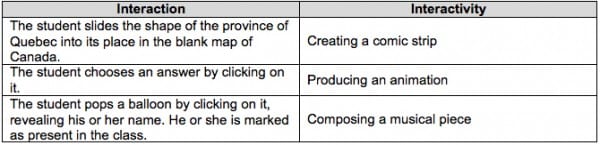

There are many ways of defining ‘interaction’. However, the generally accepted one is the reciprocal action or influence between two entities. Meanwhile, the term ‘interactivity’ is used to designate the degree of responsiveness between a person and a technology (be it device or software or both). In education, the term is also imbued with the idea that interactivity is beneficial to learning, because it implies a continuous exchange between learner and device. The table below illustrates some of the ways in which the terms ‘interaction’ and ‘interactivity’ differ when it comes to student learning.

These two categories of examples highlight some of the key features of interaction vs. interactivity:

Interactivity requires a more complex level of engagement on the part of the learner than that required by interaction. In an interactive situation, the learner is called upon to modify their behavior/responses based on the changing needs of the situation.

How can we make interactivity happen? Why is it important?

Interactivity is an integral part of the conversation around integrating technology into educational practice. As educators, we need to make the distinction between basic interaction with technology and the more complex processes involved in interactivity. In order for interactivity to take root, we must create the pedagogical situations that encourage and foster it. A student manipulating an IWB or an electronic tablet in order to answer questions or complete simple exercises is not engaging in the same kind of learning as a student creating a personal or collective work or solving a problem. The student who creates, composes, solves, produces and collaborates has more chances of engaging with the technology in a way that makes him or her the principal agent of his or her learning.

This is not to say that so-called traditional exercises are in and of themselves a bad thing. It’s just that, in my opinion, putting aside the all-too-short-lived wow-factor (and who, exactly, is being wowed?), it isn’t necessary to use an IWB or an electronic tablet to complete them (I am NOT talking here about the particular or special needs of students that make the use of differentiated technological tools necessary and justified).

Overall, I think that getting the most pedagogical value out of the interactivity promised by the new technologies at our disposal in schools is a sure way to get the most bang for our buck. We need to also keep uppermost in our minds the real value of interactivity, what it means for our students, and how to make it happen for them. For their benefit, but also for our own.

Kish Gué

Pedagogical Consultant

EMSB

Translated by Sylwia Bielec, ed.

While I agree with your premise – that students should be actively involved in using technology, not just interacting with it on a low level, I am not sure I would use the term interactivity.

Two terms come to mind for me: creating and problem-solving. Even then, I would go further, that the creations, be they podcasts, movies, comic strips…not just be “make work” but that the messages created be meaningful to the students and hopefully to the audience that will receive them. And there is where the interactivity comes in – between the creator and a dialogue with the audience!

There are many ways technology can be used to solve problems and to explore ideas in ways that would not be possible without the technology. I am thinking of applications such as geogebra where students can play with mathematical concepts or robotics, where the feedback from the way the robot moves helps the student refine his/her thinking and then the programme.

An interactive white board can be a powerful tool in the classroom. We need to make sure they are used in powerful ways and not just as expensive workbooks.

I too agree with the premise in principle, but I’m not convinced about the definition of interaction, and the distinction made between the terms interaction and interactivity.

Hugh Dubberly, Usman Haque, and Paul Pangaro discuss user interaction in their article What is Interaction? Are There Different Types? They explore a variety of interaction models and definitions of the term through the lens of design theory, human-computer interaction and systems theory. They suggest that “…by replacing simple feedback with conversation as our primary model of interaction, we may open the world to new, richer forms of computing.”