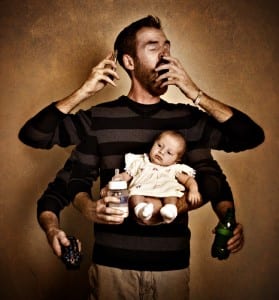

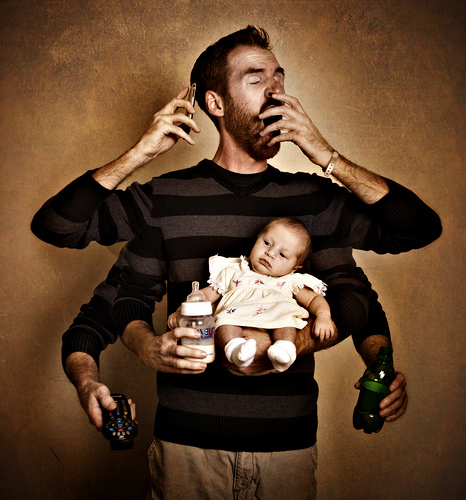

Father as Multitasker by Stephen Poff

First I will partially explain the title, as NOT being because my new baby boy woke me up earlier at 2 a.m. It’s about what kept ringing in my head afterwards, and the fact that it continued to ring at all. In part it was because I knew I was going to be writing this blog entry for others, for public consumption. That’s what made it important enough to keep me awake, to drag me out of bed, again, to seek out tea and cookies and finally a keyboard. And likewise, it certainly was not because I was being marked on it, or because my job depended on it. It was instead because I had an idea I thought was worth sharing. And also, it was because something of me was about to end up “shared” on the web, and I wanted that something to be made up of my ideas, or at least in this case my slant on a lot of other people’s ideas. I wanted to represent myself.

These two profound ideas resurfaced for me recently during a highly inspiring workshop I attended by Tanya Avrith, a Digital Citizenship Teacher for the Lester B. Pearson School Board, and a pioneer of their Digital Citizenship Program. On the one hand, she helped me reflect on why my other (teenage) son’s school assignments always ended up in the garbage. They were for marks, nothing more. And as to the other idea, she alerted me to something very important that I hadn’t ever considered, to the fact that my older son already had an extensive digital/internet footprint, mostly made up things he wouldn’t be proud of, and more often than not of things others wrote about him, pictures he didn’t take, etc. Not an ideal situation for someone searching for schools and jobs, whose college registrars and future employers would be Googling my older son’s unfortunately uncommon name.

The question is, why does this happen to him and so many others, this accumulation of embarrassing memories? It’s not for lack of information, not because he hadn’t been warned about the risks and told about the complexities of life online. It was because, and I agreed with Tanya on this, that no knowledgeable adults regularly followed him there, to guide him and set examples. And also… it was because none of his good work, his school work let’s say, followed him there either, to offset all the questionable traces left by others.

Already 5 a.m. and my work day about to begin, so that brings me back to thinking about my main dossier at LEARN, and if and how ideas like this might apply to the Social Sciences (History, Geography, Economics, Ethics in some programs, etc.). These subjects are “academic disciplines concerned with society and human nature” and as such they do serve to engage past and present events and issues, but usually from within the school walls. Obviously you can see from what I presented above I don’t think avoiding the internet during student activities is fair to our students on a personal and on a career-related level, but more than that, I think it is especially ineffective and inappropriate in the Social Sciences.

The Social Sciences Perspective

Bansky via Flickr user Ruben LC

Let’s start with what I mean by ineffective. In the social science competencies we examine, establish and balance the facts, we interpret realities then we learn ways to voice our opinions. For me these basic skills read like a list of things one cannot do effectively, not in this day and age, by avoiding the digital, social and public space that is the Internet.

Examining what? Balancing exactly what facts? When it comes to subjects like history and geography, are we really talking about facts in textbooks alone? Are we meant to avoid current sources and interpretations, meant to ignore the news and the myriad opinions of the non-experts, the young and the old, and the stories from those who “were actually there”? Sure, the number of sources in our digital world is vast, and many are even unreliable, but is that a reason to filter them out or avoid them altogether? Shouldn’t we be teaching students how to sift through them, how to use search engines effectively, how to compare online sources?

Interpreting, but how? Voicing our opinions, but how, where, and for whom? When we talk of creating good citizens, do we really mean to create citizens who avoid interpreting events, past and present, based on current representations of those events? Do we want to form students who can only write their opinions in a laboratory, for their teacher’s eyes only? In the real world, modern historians … Okay, I will get to that one a bit later, for now let’s say…people. In the real world people balance and reflect on all kinds of sources. They might read the Gazette, catch a clip from CNN, then watch a feature documentary on CBC. They might actually look it up in a library. In Quebec even Anglophones check out La Presse occasionally, or watch half of Tout le monde en parle on Sunday nights.

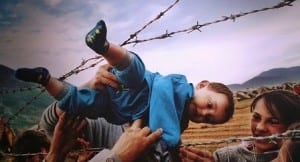

Fleeing Kosovo. Flickr user cliff1066™

The world has opened up, and mobile devices help. BBC and Al Jazeera now offer great English-language news services on devices like the iPad, and following a link from any of the above sources can now lead you to unexpected places, to bloggers and tweeters on the ground in Israel, Africa, China or Iran, to powerful and personal images shared via Flickr that scatter a thousand words worth of information across your screen in an instant.

Okay, not all people balance and reflect. In the real world, people also read short articles recommended by friends on Facebook. Are those documents the best sources of information too? Maybe, and maybe not. But either way this is one way people, probably even academics, get information, by sifting through even these social sources, through all sources.

So, given all that, then where do people, or let us now say citizens, effectively voice opinions? Perhaps not on Facebook, which doesn’t lend itself to “reasoning historically” and doesn’t encourage one to really develop an articulate argument. But maybe, maybe even on Facebook, and that possibility is key here to what I am trying to say. What guides educators should be this: any forum that allows and inspires students to articulate their opinion, and encourages and allows them to examine, establish facts, compare, accept and understand difference, any forum that does that is good.

For whom?

Okay, now it is a few days later and I am in the café across from my local, public library, and I am thinking about a conference I went to mid-April, which had also been what had inspired me to stay up all hours blogging this all down. To write, for whom? That was the question. For you, of course, is the answer! But also and in general terms for the larger public domain, to scratch out thoughts that inevitably become a small part of a larger history, that might take part in a dialogue, or that might completely disappear (but that’s okay, really) like the slow fire of so many old books printed on acid paper. Now, I am indeed talking about a kind of historian, and the conference that inspired me was the National Council on Publish History’s annual meeting in Ottawa, and in particular a workshop series I attended entitled “Connecting Communities: Social Media and Public History Practice.”

What is public history? Okay, I am going to swipe this one from the NCPH site directly:

“Public history describes the many and diverse ways in which history is put to work in the world. In this sense, it is history that is applied to real-world issues. […] Public historians come in all shapes and sizes. They call themselves historical consultants, museum professionals, government historians, archivists, oral historians, cultural resource managers, curators, film and media producers, historical interpreters, historic preservationists, policy advisers, local historians, and community activists, among many, many other job descriptions. All share an interest and commitment to making history relevant and useful in the public sphere.”

Relevant, useful, local. Archivists, curators, and jobs! I really like those words. In my eyes, this conference was about social science students (albeit life-long students) actively being citizens by “doing” history, and actually making a difference in the real world.

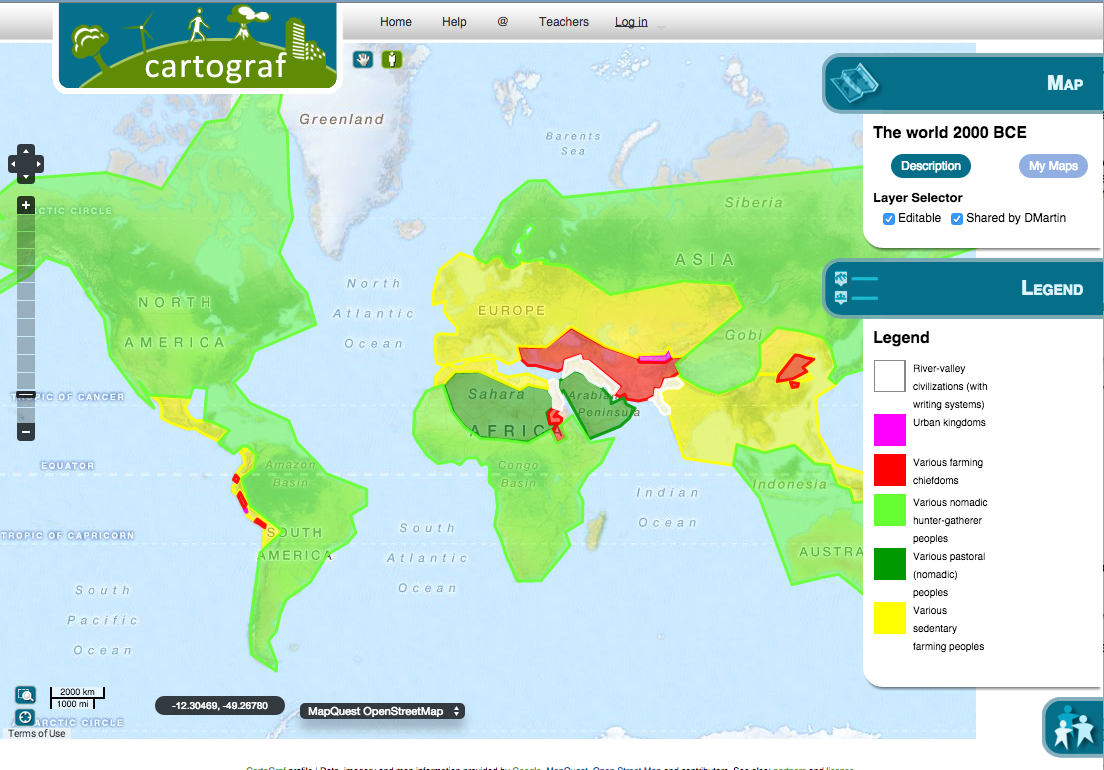

Here are a few quick examples I caught at the conference: University students develop content for a mobile application that maps the history of Cleveland, process repeats for Spokane and other cities, regular users of the application can submit their stories and history becomes on-going and active. Facebook is used to disseminate unidentified photos of a ghost-mining town, so as to identify the places, people and experiences in them. Twitter is used to present the diary entries of an individual farmer and soldier during the War of 1812, in daily entries that coincide with the same dates in 2012, in order to better represent the timing and sequence of events that occur in actual economies of war today. Tumblr is used to reflect on historical ideas themselves, and on how social media techniques and popular culture are used to disseminate information in public life.

Public life=my students’ social world, the community, their small tribe as connected to other small tribes, along paths I absolutely need to dare to cross.

And that’s it. These are some of the many reasons why in the middle of the night I woke up thinking that school really should be more social, and that social sciences (and maybe all subjects) should be more public, and why now, finishing up this blog entry over a cold coffee across from the library, I might just walk across the street to see what that cryptic exhibit poster in the window really means to me, and what treasures I might find there to take home and read, contemplate, pass on.

Wonderful ! I am honoured that my session had such an impact on your thinking. This is such an important area of discussion and the word needs to get out. Thanks for continuing the good fight.

Thanks Tanya! Also thanks for the retweet. Hey… Can you look at other comments below this and reply to that thread about kids at an early age? You remember you mentioned that school board in Maine that starts them off young?? How? What age?

Interesting thoughts Paul. It’s true that our students already are social and already have public traces (whether they’re aware of these or not), so it’s important that they be aware of how to interact in these forums – and what the consequences of their activities/choices may be. How social and how public ought they to be? This is really a question that parents and children who are active on the internet need to discuss… and something educators also need to bring into the classroom as well. There is certainly a large parental role/responsibility here – and a bit of a mine-field for educators at the elementary and high school level where our students are not of legal age.

A couple things… Yes, I caught that about parental responsibility for sure. I thought we were being that, by being on his lists and checking now and then, and informing. Point I was making was that wasn’t enough, at least for us. Really needed to be doing something actively with our son. Like working on a blog or family site or something. I think. Anyway, in many ways already too late at 16.

Actually, Tanya might chime in, but she referred in her workshop to a board in Maine that has their students active online (maybe in various secure or other less secure environments) right from primary grades. Yes, a minefield in some respects, but when it is done right students (might) end up with a presence and experience that is positive and established even by the time they reach legal age.

Hi Paul,

I think the post brings up many interesting questions and ideas, and Wendy’s question of age and levels of online interaction is one I struggled with before experimenting with student blogs this year. I think that for your older son, being part of an early wave of social media may mean that he is finding his way as we find ours as parents, but with younger kids, like my 12 year old son, we can already use stories and examples in the media to help guide his online activity and help him make good choices about what gets put ‘out there.’ The idea of cultivating a positive digital footprint was an important part of the webinar Sylvia and Susan held earlier this school year, and it was an important factor in getting me to help my students begin with blogging. As a class we developed a code of conduct that mirrors the kinds of behaviour we want to develop off-line as well, and parents got behind the process. The blogs are open only to classmates and parents, but it’s a step. It isn’t perfect, and requires a whole new level of teacher supervision, but I don’t think we can avoid it any longer, and given that most parents may not realize the impact of social media and other online interactions, we need to throw our hats into the ring and at least have the hard conversations. In a culture that is increasingly worried about liability and responsibility, in which we are applauded for hovering over our children, exploring new arenas of interaction can be scary.

As for the other examples you give of history and social media and the uses of new technologies to share and discuss – what a wonderful time to be a teacher! So many new avenues open to us to explore and to excite the students -thanks for posting new links for us all to check out.