Irene’s work with her students is so inspiring. But when asked to share it with others, she declines, saying that it’s not really that great.

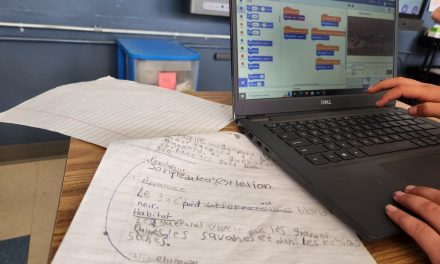

Dan is excited about making a movie with his students, but he feels that he needs to really master the latest software, and also learn more about sound editing before he tries. So no movie this year.

Elsie wants to try a new literacy approach, but there are so many facets of it that it seems overwhelming. Maybe next year, when she has read more and made a better plan, she’ll try it.

What do these stories have in common? They are all about people afflicted with a malady of our time: Perfection Paralysis. In fact, many of us are afflicted with it. Ironically, this blog post almost didn’t see the light of day because of it.

What is “Perfection Paralysis?” I would define it as the inability to let go of a work out of fear that it is substandard or imperfect, or to avoid trying something because our mastery of it is inadequate. It is a personality trait that many of us share, but it is also learned when we set unrealistic expectations for others as well as ourselves. For some, our natural fear of failure has escalated to a fear of imperfection.

A few months back, a newspaper article prompted a conversation with a colleague about the concept of perfection, and how we put enormous pressure on ourselves to be perfect to the point that it becomes paralyzing. The letter provoked some deep thinking.

![By Marcus Quigmire from Florida, USA (Perfection Uploaded by Princess Mérida) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blogs.learnquebec.ca/files/2014/01/2978993141_f6c3fdbf34_b-300x200.jpg)

By Marcus Quigmire from Florida, USA (Perfection Uploaded by Princess Mérida) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

“I’m not good with computers”;

“It’s not ready to share with others”; or

“My work isn’t good enough to share.”

The sentiment is understandable. We want to put our best face forward, and what we do not know well is often intimidating, or even threatening. But I am often left with the impression that many people feel that they must possess either a high level of expertise or a natural aptitude in order to be able to use technology.

When I attempt to introduce a professional educator to something new, and the first line of response is, “Before we begin, you should know that I suck at this,” then what should my reaction be? Comebacks like this make work for people like me much more difficult, because they imply defeat.

This frustrating starting point is not exclusive to technology, but the curious way that people perceive computers and technology has preoccupied and driven me since I entered education 20 years ago.

Computing devices are unfeeling, precise, calculating, and unforgiving of error. Perhaps the perceived threat is that if we are not perfect, we are somehow inferior. There is a social aspect to it too. No one wants to be caught out looking less than competent in front of his or her students and colleagues. Considering that students are steeped in technology these days, it is still hard for many teachers to accept that they are not necessarily the experts in the classroom when it comes to technology.

So how do we address the problem of “perfection paralysis?” Is the solution to lower our standards?

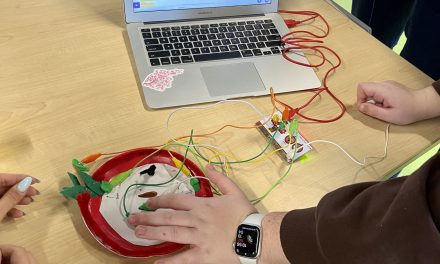

I think that when we look at the work of our colleagues and students, we tend to be too pedantic. The result is to focus on minutiae rather than taking overall quality into consideration. If a teacher has used technology with their students to produce something, and we focus on small details rather than the big picture, it takes away from the fact that the teacher has moved forward in their use of technology. It puts the pressure on individuals to focus on those details and cultivates perfection paralysis.

Let us celebrate progress and encourage engagement rather than resorting to pickiness.

The strategy that has worked best for me over the years has been to create a non-threatening atmosphere in which teachers can experiment and explore without repercussions as they become more familiar with technology tools. The key is to cultivate a climate of discovery and experimentation as opposed to one of judgement and unattainable standards. After all, we don’t expect our students to be perfect the first time around. We encourage them to experiment and take risks. If everything had to be perfect right away, we’d never get anything done!

It’s about time we give ourselves the gift of ‘just fine’ as opposed to ‘best’. The gift of ‘try and see’ instead of ‘has to be perfect’. One thing is for sure: we’ll all be moving forward and our students will benefit from our spoken and unspoken lessons of experimentation.

****

To read about another educator’s struggle with perfection paralysis check out this blog post by Vicki Davis from Cool Cat Teacher Blog.