How do you help your students discover local and global contexts in History and Geography classes? Tell us by commenting below, or tweet to @learnquebec

In the Quebec education system the notion of the “elsewhere” society appears in several programs, and especially the social sciences: Students are encouraged to “compare here and elsewhere, past and present, thus making them aware of change and diversity.” However, for teachers making this happen is far easier said than done. It’s a question of time (class time, but also time periods) and of place (but sometimes we forget about location). But before we get to all that, let’s ask if and why it might be interesting and useful for students to learn about places and cultures other than their own.

Historical events presented “in context” can certainly help to explain things (causes, effects, reasons), but one could also add that most contextualization can be extended to a global scale: geographical and historical realities happen in the world, one area’s disasters affect another area’s success and growth, and vice versa. Always a compelling notion — that we are not alone in our suffering or success — but does that make learning interesting or fun? My own experience as a teacher of history tells me that, if anything else, “difference” is something that students do appreciate. Learning about other areas of the world, completely new areas I mean, offers them a break from the mundane, the routine. And, importantly, it serves our educational goals, by giving students a fresh perspective on our own region, our culture, our story, which refines and deepens their understanding of what they are learning in class.

Recently I approached a certain teacher with these questions on my mind, after being intrigued with how he using was our Cartograf mapping tool in his history classes. Daniel Martin teaches the secondary cycle 1 ancient and world history course at Chambly Academy (RSB). Granted, compared to other more Quebec-centered programs, this course already permits (and allows some time for!) an exploration of world histories, other societies that informed and contributed to our own (Greek democracy explaining our political system, the Christian reformation the roots of our religions, etc.). But as Daniel showed me, just learning about these few societies for comparative purposes isn’t enough. What was happening all around the world is also essential to fully understanding each era, each place:

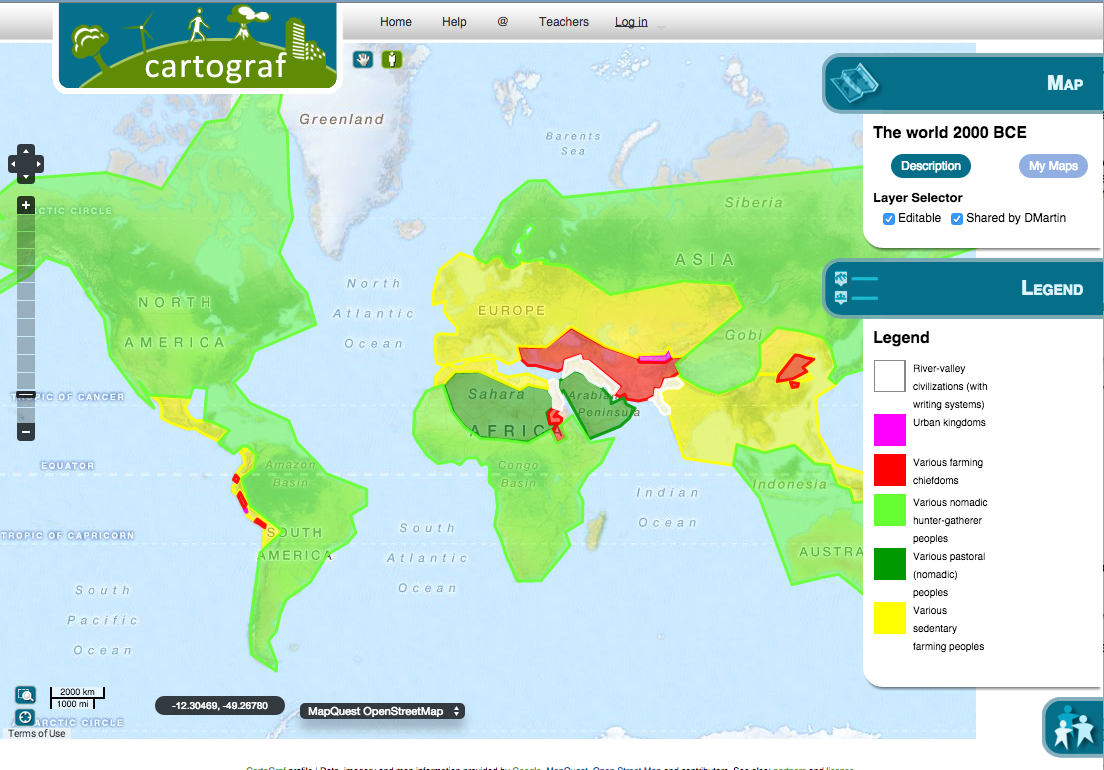

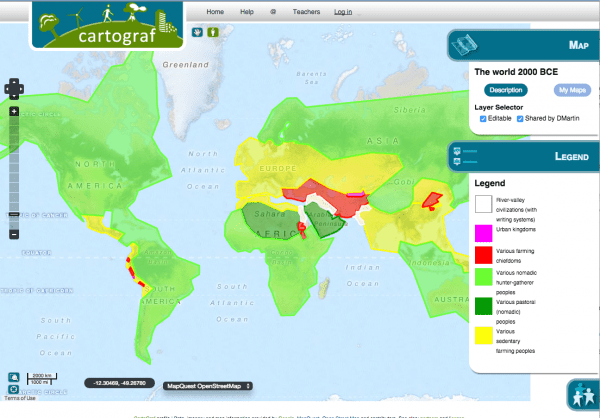

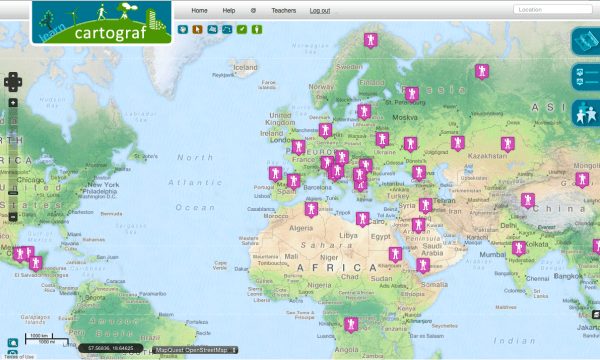

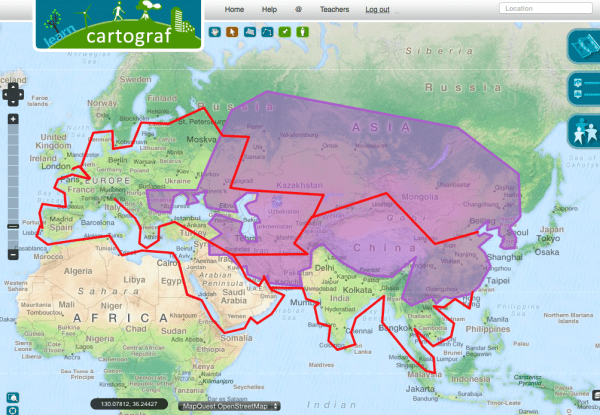

[Below I paraphrase some thoughts Daniel and I shared, along with pics of his Cartograf maps.]

When you don’t show students what else was going on in a given time period, they begin to believe nothing else was happening at all at that time. If you teach only certain “important” civilizations, students get the impression that no other civilizations existed at the same time. This gives them a skewed and incomplete representation of the era, of the time period. Other cultures must have existed in other time periods, they say.

Secondly, in terms of location, students not only misunderstand distances and placement in a global scale, but they also don’t realize there were different peoples and cultures “in between” the two or three societies they study. They conceive of the world as a mostly empty and disconnected patchwork of selected societies, which it never was and never will be.

And finally, when neglecting to consider other cultures in distant places, students easily loose sight of the varied evolutionary paths that different societies follow. They get the false impression that everyone changed at the same time and same rate. When instead you show them certain evolutionary steps (sedentarization, for example) on a more comprehensive world map, they quickly see that during any given period some societies were still nomads while others were living in cities while others were trading across the seas.

In 500 BC, while the Greeks were developing city-states, the first democracies and various other aspects of what became our culture, throughout the world other peoples were changing too. Democracy happened, philosophy happened, all at a time when Greeks were in contact with a wide range of cultures in different stages of evolution, but also when they were completely unaware of other cultures. Change and culture happened everywhere, just differently and at different rates. And that should remind us how some aspects of our culture arrived via completely different routes too: think about aboriginal influences on New France, about Eastern influence now through immigration, about a growing African influence in an inevitable global future.

A complacent and superficial acceptance of traditional terms and approaches to history is sometimes the cause: The Middle Ages were called “middle” by 19th century scholars who saw it as a culturally empty time between two periods of enlightenment. But were these so called Dark Ages dark for our whole world? During this same period Islamic cultures were living their golden ages, expanding on the sciences and logic of the Greeks, eventually passing it all back to Europe via translations of their texts that sparked our own Renaissance! And what is more, even during that same time period of so-called darkness Europeans themselves continued trading to the east, and cities developed at home and along those routes. But again, don’t imagine easy paths through empty lands all the way to China. Across those same years the Mongol Empire expanded to cover most of that known world!

This exchange of thoughts with Daniel helped me reflect on my own teaching and curriculum design at LEARN, which has always been highly suspicious of the language in the provincial programs, of all programs really. I remember how I questioned the way Native peoples were all said to share the same spiritual outlook, all said to share the same relationship to the land. While certain commonalities were obvious, I admit, I couldn’t help but think that the program de-valued the many distinct societies that existed at the time. And so I helped students to discover those unique cultures and experiences through research, and as such to fill in the timeline, to fill in the map.

And finally, the exchange also helped me to reflect on how we view our world of the present day, on how easy it can be to compartmentalize according to what makes the news, or according to what language or culture is more familiar or reachable. We don’t consider the details about what or who is actually there, we don’t investigate what is beyond or between the disaster zones and the clashes of belief, will and power. But I do now, I can’t help it, when I see a map of the world I see it differently. Immediately I ask questions about what is not highlighted, about what is not shown, about what is elsewhere. I zoom right in, and what I find there becomes uniquely my own discovery. The process itself is fun and revealing. And I can’t help assume that it would be the same for students too. What are your thoughts?

> Hi Paul,

>

REALLY enjoyed reading this. VERY true – – – how we get focused and partially blinded by the shiniest of stars – – – – leading to eras being thought about too narrowly in terms of events, concepts and locations – – – – and in combination with the tradition of over-generalization through reliance on certain historical ‘terms’ and ‘catch-phrases’ that limit rather than broaden the scope of historical investigation and historical imagination. Your emphasis on being WARY of historical tunnel vision is a perfect REFRAIN for the history classroom – – – inviting EXPANSION of conversations and inquiry in the history classroom – – – and literally instilling the habit of looking at all movements in the brush – – – and to remind us to continually stop and look around while we pursue rabbits as we do so loyally. Thanks for writing this – – – MOST sincerely.

>

Dan Hedges

Social Studies Consultant

Sir Wilfrid Laurier School Board

I would love to be in your history class, Paul. I don’t recall my own teacher sharing such points so powerfully.

Daniel is a wonderful teacher and we are very happy to have him with us at Riverside.

This blog entry is good inspiration for all teachers out there! I will share it! 🙂

We are very happy to have Daniel back with us at Chambly Academy where he has worked for most of the few three years. He is an innovator and a total professional. His example is an open and powerful one in our school.

Michael Languay

Principal – Chambly Academy