When my daughter was a preschooler, she considered herself to be a great artist. Tongue out, brow furrowed, she would cover page after page with blobs of watercolour or furious lines of water pastels that she would then wet and smear about. She would bang away on her (real, not toy) xylophone and proclaim proudly that it was her Music, accompany herself on the keyboard as she invented stories out loud to herself, dance whimsically around the house whenever any classical music was on. And then. As elementary school wore on, she slowly but very surely began to divest herself of her spontaneous artistic pursuits. She was “not as good as Kiara” at drawing and “Camila played the piano better than she did” so she didn’t bother accompanying herself on the piano when she invented stories. Nevermind that her parents were proud amateurs of various arts, and even taught other amateurs in turn. Something had changed.

How does a growth mindset apply in the arts? How do we as educators make choices that will help move us and our students towards a growth mindset? What are the benefits of fostering a growth mindset in learners? These are the questions I’d like to explore in this post.

Looking to ourselves first

By now, most of us know about Carol Dweck, PhD, and her work on the growth mindset. As educators, it is hard to find many among us who disagree with her findings that intelligence is not fixed, but is instead a mutable characteristic to be developed throughout your whole life. It came to most of us as a eureka moment – of course intelligence is not fixed! But what about… artistic ability? Or creativity? Even Carol Dweck wrestled with these questions:

Despite the widespread belief that intelligence is born, not made, when we really think about it, it’s not so hard to imagine that people can develop their intellectual abilities. The intellect is so multifaceted. You can develop verbal skills or mathematical-scientific skills or logical thinking skills, and so on. But when it comes to artistic ability, it seems more like a God-given gift. For example, people seem to naturally draw well or poorly.

– Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol S. Dweck

Thus, as arts teachers, we need to first examine our own views of the role of the individual in their artistic endeavours. I need to ask myself: Do I think that people either “got it or they don’t”? Do I think that some people have talent and that those people are really the only people who should bother making art? Am I impressed by what I perceive to be the natural ability of people, and how does this colour my interactions with those and other learners? Ultimately, as educators, we need to move towards the understanding that anyone can develop any skill or competency, and that our job is to facilitate that development:

Just because some people can do something with little or no training, it doesn’t mean that others can’t do it (and sometimes do it even better) with training. This is so important, because many, many people with the fixed mindset think that someone’s early performance tells you all you need to know about their talent and their future.

– Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol S. Dweck

When people enter my dance classroom, they are dancers. They are not future dancers or maybe dancers. They are dancers today. All the choices I make about what to say to them, and what we should work on is based on that belief. In our respective arts classrooms, two things we can control as educators are the words we use and the activities in which we engage. Having these choices grounded in a growth mindset can lead to very powerful shifts in our arts classrooms.

Growth Mindset: What we do

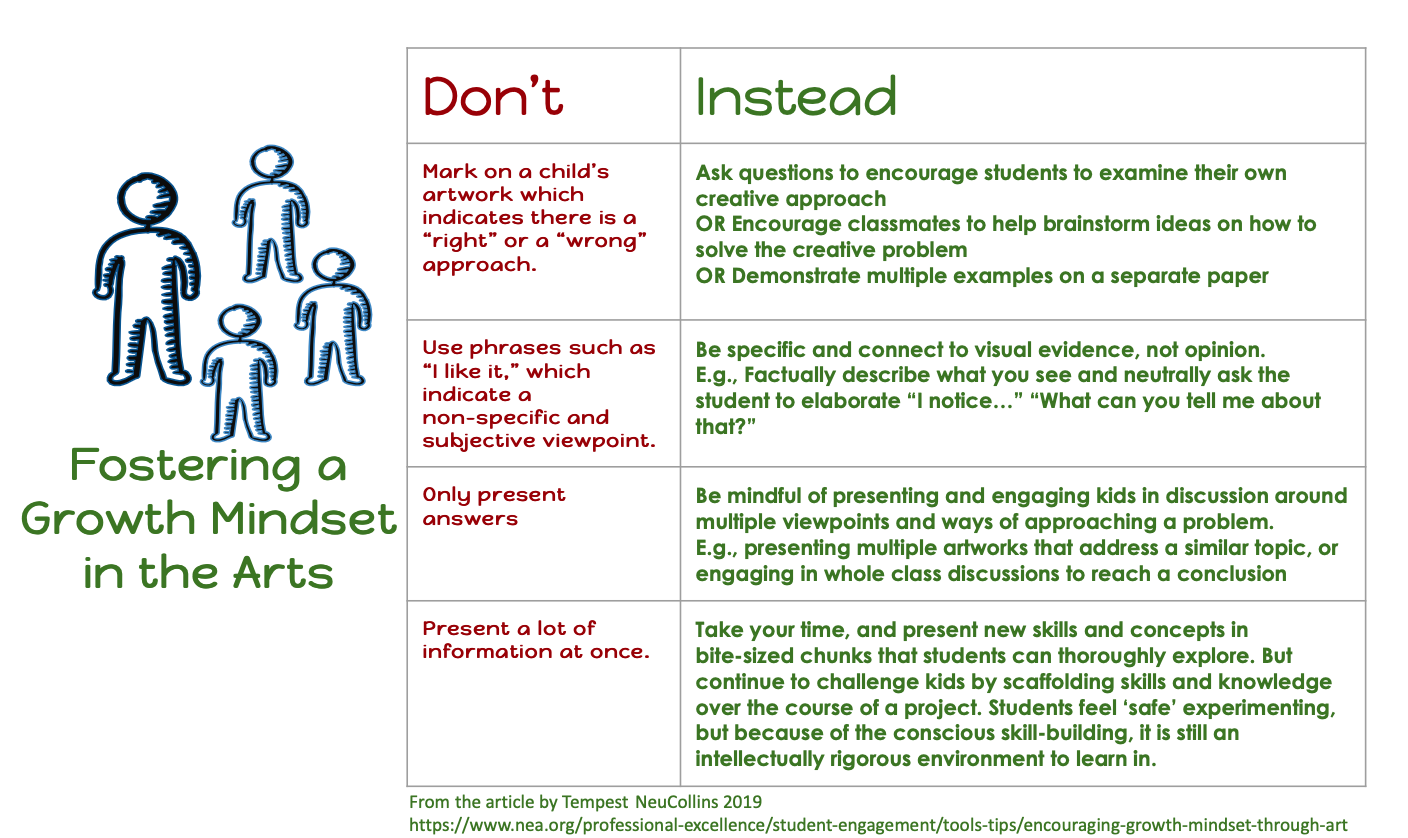

Tempest NeuCollins writes in their article for the National Education Association (USA) about the pretty Pinterest lessons that have been popular for some years now. You know the ones, with student samples attached to show teachers what the end product will look like. A full display wall of art pieces each mirroring each other in an almost pop-art-like array. They are practical, because they often provide teachers with clear objectives and a breakdown of activities. Administrators approve of these, as they photograph well and decorate the hallways for visitors.

Tempest NeuCollins writes in their article for the National Education Association (USA) about the pretty Pinterest lessons that have been popular for some years now. You know the ones, with student samples attached to show teachers what the end product will look like. A full display wall of art pieces each mirroring each other in an almost pop-art-like array. They are practical, because they often provide teachers with clear objectives and a breakdown of activities. Administrators approve of these, as they photograph well and decorate the hallways for visitors.

But what is the experience like for students? What do they make of the easy-to-follow instructions, clear steps and pre-defined outcomes?

It is easy to think that the same things that make these art lessons so enticing for teachers would make them engaging for students. But the student experience is often quite different. Not all students find clear instructions compelling, because the fear of doing it wrong is ever-present when it is too clear what the “right” way is. Pre-defined outcomes make comparison with peers inevitable and students are savvy when it comes to what things “should” look like. All these aspects of the student experience may lead to a fixed mindset as opposed to a growth mindset, and make students less creative and autonomous and more self-conscious and needy. This is not to say that we should eliminate all of the tidier learning activities altogether – just that we should use these activities sparingly, and make sure that we emphasize the process, and not put too much focus on the product.

In my dance classroom, I can show students sequences to learn and reproduce, which is sometimes necessary for technical reasons, but I also need to provide students of dance with opportunities to improvise, to come up with their own ways of linking together movements, and to express the music through movement in their own unique ways. Open-ended tasks, reflective questioning and compelling concepts will lead to greater engagement and also to some of the more repetitive (read: boring) but necessary aspects of art-making like practising and refining technique.

NeuCollins writes about how they noticed increased engagement on the part of students after they made the shift to visual arts projects that centered around a concept or idea – such as anthropomorphic animals, explored through art, literature and popular culture. This approach is different from exploring the style of a particular artist or even a single artwork. In the new approach, students were given what the QEP calls a stimulus for creation, and a process with which to engage as opposed to a procedure to follow. NeuCollins reports that engagement soared,

And this was because they had a safe place to explore their own ideas, tell their own stories, and yes, make and solve their own mistakes. Through these process-focused projects, my students began to recognize that there was more than one way to approach the problem, and that every solution, when well executed, offers a unique perspective. As a result, they learned that, instead of mistakes being a failure to replicate an ideal, they are opportunities to expand ideas and use the process as an opportunity to creatively problem solve.

– NeuCollins (2019)

In the dance classroom, instead of focusing on teaching choreography or sequences, we can offer students reasons to create and ways to improvise, then give them the time and space to come up with ideas and try them out on the dance floor for each other. Even when working on a play, the process of working out how to do a scene can be open-ended and approached with a problem-solving mindset. When it comes to the performing arts, Gerald Klickstein, a music educator, noticed that his students with a fixed mindset tended to suffer from stage fright more often, because as Dweck pointed out, a fixed mindset “turns everyone into judges instead of allies” (Dweck, 2007, p.67). Shifting to a growth mindset could lessen stage fright for performers and lead to a playful and curious attitude for young artists.

Growth Mindset: What we say

We can choose to prioritize process over product through the learning activities that we design for students, but equally important are the conversations we have with students about their process and product – and this, even when we choose learning activities that lead to very similar student products. Because the arts have a sensory aspect to them – we hear music and speech, we see works of art and people dancing, performing, etc – it is easy to be descriptive when talking about a student’s work or process, as opposed to giving your opinion as to the quality of the work itself. Highlighting process and mirroring a student’s artistic actions back to them is our superpower as arts educators and one we should be using to greater effect. Some powerful process-oriented sentence starters and questions for educators could be:

– What I see you doing now is ___________ / called ____________.

– What do you think you should do next?

– What led you here / what was your thinking behind this choice?

– How might __________ help you with your work?

– Who in the class could help you with your work?

– Remember when we talked about _______________?

– Something that is new in your work compared to your last work is __________.

Why should we as arts educators care about fostering a growth mindset in our students? We have so little time with them, and a lot to get through. One might argue that a growth mindset is primarily what being a lifelong artist is about. After all, art is about curiosity and perception, about knowing yourself, about iterations, about the next piece. For artists everywhere, art is primarily about the process, so why not focus on that in our arts classrooms? As I said elsewhere, making art is an act of courage, whether you are a working artist or an arts student. Teaching students how to adopt a growth mindset is a gift, both for them and yourself. Students who approach art-making with curiosity instead of being filled with self-judgement are a pleasure to teach and will approach whatever you suggest with enthusiasm and playfulness. They will have their own ideas to express and the less judgement there is – whether from the teacher, the task or themselves – the more their ideas can shine through. We should all be so lucky.

References

Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Klickstein, G. (2020, June 1). The growth mindset – music and creativity. MusiciansWay.com. https://www.musiciansway.com/blog/2010/07/the-growth-mindset/. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

NeuCollins, T. (2019, March 18). Encouraging a growth mindset through art. National Education Association. https://www.nea.org/professional-excellence/student-engagement/tools-tips/encouraging-growth-mindset-through-art. Retrieved December 14, 2021.