This post was co-written with Heather Morrison (Teacher, Perspectives II High School, EMSB) &

Ruwani Payoe (Teacher, Program Mile End High School, EMSB)

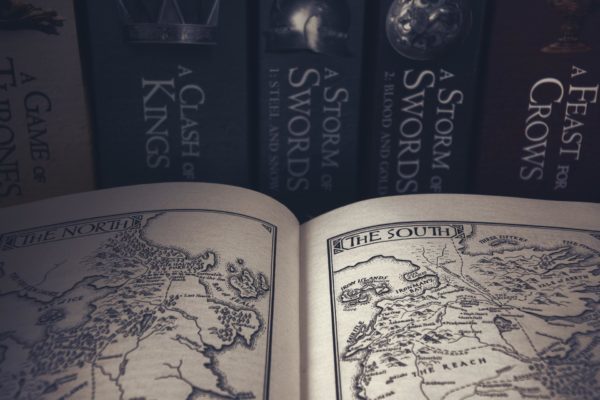

Even as a 9th-grade English teacher working out in rural Quebec, I knew the “whole world” would always be our stage. From my first classes teaching novels, poems and plays, it was not enough to just read them for good prose or style, or for truths they contained about life and living. I had a penchant for place! Classic novels like Walkabout took us to the Australian desert, The Chrysalids brought us to a future Labrador, and to discussions about whether the final destination of New Zealand was even reachable in that apocalyptic world without vehicles. For me, it was all about territory and terrain, and then eventually about cultures too. I even ended up dividing my class, so each row represented a different country: One group read books from Africa, another from England or India, and some even tackled translated texts from Italy, Spain and France. For us, it became as much about where we were, and what being there meant, as it was about the story being told. It was about letting our minds leave the safety and familiarity of home, if only for a few moments a day, to trace someone else’s experience, and make it our own.

Last year, I met two teachers at the English Montreal School Board, Ruwani and Heather, who were also passionate about place and culture, and also identity, history and tradition. They were interested in employing more interactive maps and mapping experiences in their English Language Arts (ELA) classes. They received a Professional Development and Innovation Grant (PDIG) to complete their work and their project entitled “Situating Our Learning in ELA Using an Interactive Reader Map” brought us together. They saw LEARN’s online mapping tool Cartograf as a possible answer to their project’s goals. So late last year I came in to help direct the technology and to share and incorporate some of my own experiences using Cartograf in Social Sciences over the years. I recently interviewed them about the project and their experiences.

Last year, I met two teachers at the English Montreal School Board, Ruwani and Heather, who were also passionate about place and culture, and also identity, history and tradition. They were interested in employing more interactive maps and mapping experiences in their English Language Arts (ELA) classes. They received a Professional Development and Innovation Grant (PDIG) to complete their work and their project entitled “Situating Our Learning in ELA Using an Interactive Reader Map” brought us together. They saw LEARN’s online mapping tool Cartograf as a possible answer to their project’s goals. So late last year I came in to help direct the technology and to share and incorporate some of my own experiences using Cartograf in Social Sciences over the years. I recently interviewed them about the project and their experiences.

What is this PDIG about?

Our PDIG entitled: “Situating Our Learning in ELA Using an Interactive Reader Map”, proposed ways to “address the Media Pursuit of the Advanced 5 Balanced Literacy Framework by creating an interactive map for students to track their reading experiences and consequently their learning.”

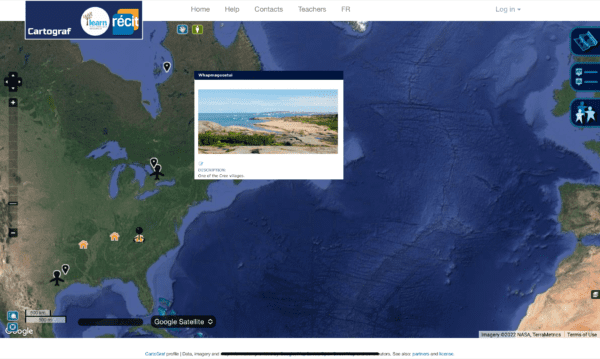

Essentially, we are hoping that students will locate their various texts on a world map and use places on their map to talk about how their texts contribute to a broader cultural conversation: How does their text do the work of colonialism? How does their text reveal internalized misogyny? How does their text speak truth to homophobia? We saw Cartograf as a platform that could work well for a teacher-led guided research activity, but also for student-directed research projects. In class our students read novels, articles, poems, and multimodal hypertexts. We wanted students to be able to interact with different text types, research their authors, and research the locations related to the writer’s experiences and those of the characters too. Cartograf would then allow students to create “an innovative reading portfolio that promotes a nexus of cross-curricular learning; multi-literacies as well as digital literacies.”

What was your inspiration?

We were inspired by Joy Harjo’s work and the interactive map available at Living Nations, Living Words. Harjo’s project curates poets and poems based on the theme of place and displacement; focusing on the idea that poetry “emerges from the soul of a community, the heart and lands of the people,” inclusion on the map is guided by four touchpoints: visibility, persistence, resistance, and acknowledgement.

Why are projects like this needed?

In the Living Nations, Living Words project, Harjo writes of place: “We all emerge from a place. Everyone does, whether you are mineral, plant, animal or winds. Our identity springs from place….” We feel it is instrumental for our students to find their place in the world, especially now, after our collective experience of virtual school.

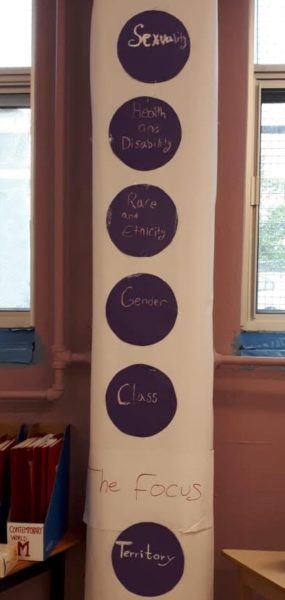

Our project is about looking at the importance of place in any story, and it is also a reading inventory – proof of reading. In particular, when considering the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action, teaching about place is fundamental: Teaching about place is essential to an understanding of a world that includes Indigenous traditional lands and world-views. Learning about place in a story helps us to develop a new understanding of ourselves, and of where we fit in this world. To engage students in a conversation about indigenous issues, we have to focus on territory. In fact, one way to begin our respective learning units, we thought, would be to discuss various Indigenous issues, examine and respond to Joy Harjo’s poems, in order to create a land acknowledgement for our schools in our region. High school students are ready for conversations about land claims and treaties. This was confirmed at the beginning of the school year when students added ‘Territory’ as a FOCUS topic to our social justice pillars.

We also feel that projects like this are important because they show how maps too can be a ‘text’, a map can tell a story. The maps we produced could flush out and represent details in the class novels and poems better than traditional written responses. Equally true, as Joy Harjo’s map illustrates, maps are better at representing buried perspectives, or perspectives obscured by other maps. Reading the map as a ‘text’ is important too.

What about the project you had them do in your class? What were your goals?

Heather: We used a ‘literature-circle’ approach and students were given a choice of reading 5 graphic novels where place was integral to the story. They were then tasked with mapping out the places mentioned in the story while being as specific as possible. They learned how to find and examine these places with the different tools available: to zoom in as close as possible to the locations in their novels; to look at what was close by; to use satellite and even street view to examine the terrain and the territory.

Then the students created a slideshow document and considered the following questions:

-

- Where does the story take place? (There may be more than one place/slide)

- How does the social context alter or contribute to the meaning of this text?

- What perspective has the writer taken? Excluded?

- Why did the writer write this text?

Using the ‘Points of Interest’ pins in Cartograf, they would transpose those slides/ideas onto the exact location they felt was appropriate. The choice of location was ultimately a personal choice and one that they explained with their own logic and interpretation.

Ruwani: Our project actually began with mapping out information about the writer, and the writer’s ‘residence’ on earth. This could mean their place of birth, their past and current residences, or, for writers who moved around a lot, all of those and more. We also used a ‘Literature-circle’ approach. Students read graphic novels/illustrated texts in their circle. Some graphic novels engaged a writer and an illustrator. For example, Dave McKean illustrated David Almond’s text, Mouse, Bird, Snake, Wolf. So students had to map two artists. We were exploring the ‘big idea’ of the writer’s craft, and considering a writer’s political, cultural, and ideological influences. Class discussion about writers was noticeably shaped by the maps that students created.

Ruwani: Our project actually began with mapping out information about the writer, and the writer’s ‘residence’ on earth. This could mean their place of birth, their past and current residences, or, for writers who moved around a lot, all of those and more. We also used a ‘Literature-circle’ approach. Students read graphic novels/illustrated texts in their circle. Some graphic novels engaged a writer and an illustrator. For example, Dave McKean illustrated David Almond’s text, Mouse, Bird, Snake, Wolf. So students had to map two artists. We were exploring the ‘big idea’ of the writer’s craft, and considering a writer’s political, cultural, and ideological influences. Class discussion about writers was noticeably shaped by the maps that students created.

We then proceeded to map the places actually mentioned and represented in the texts, which enabled students to explore another big idea – that of cultural appropriation. A cogent case was when students who mapped The Outside Circle, which is set in Edmonton, Alberta, and students who mapped The Silence of our Friends, which is set in Texas, considered the question, ‘Who knows the real story about what happened there?’

In a related activity, and for comparison and other purposes, we also mapped a journey taken by Cree and Inuit to protest the James Bay and Northern Quebec Hydroelectric project. This was a truly collaborative activity because we divided up places on the journey so each group of students could work on one part of the project.

How did it go?

Students enjoyed the experience in a number of ways. Think about how video games (World of Warcraft, Mario Bros, ZELDA, etc.) allow students to walk through places. Well, using Cartograf was a bit like those games for some students. Students could visit the locations in their stories. The map work, but also the research, allowed them to find out more about the settings and the people in them. The platform also allowed students a chance to show their peers those places in their novels and other texts. Sharing maps with others was like sharing their route through the game of their story.

Both experiences provided other visuals: the satellite and street views in Cartograf, but also the videos they found, or other images too that they then used in their slides and eventually localized into points on their maps.

What obstacles did you come up against?

Like with so many things we do in education, there were at times extenuating circumstances in the school itself that prevented the project from going ahead as planned. The project did not quite roll out during the timeframe we expected, and sometimes the flow had to be picked up at a later date. Although this was manageable, it was not always ideal.

But there were other more interesting problems that we encountered that are sometimes comical or ironic that are worth sharing. For example, how do you map out books that are set in the afterlife, like in Ghostopolis? What about books set in outer space, or on Mars!? The maps did not easily allow those students to participate in localizing their exact points. Sometimes related points had to be used. The plus side of that though is it forced students to be creative and to somehow associate Earth and present-day places with those in their stories.

But there were other more interesting problems that we encountered that are sometimes comical or ironic that are worth sharing. For example, how do you map out books that are set in the afterlife, like in Ghostopolis? What about books set in outer space, or on Mars!? The maps did not easily allow those students to participate in localizing their exact points. Sometimes related points had to be used. The plus side of that though is it forced students to be creative and to somehow associate Earth and present-day places with those in their stories.

There were other questions that were more difficult to deal with. For example, if this text is a memoir, then why does the author use a fictional town or fictional place, like in the graphic novel This One Summer? And again, how do you map that? Do you try to recreate the fiction or try to explain it in real-world terms and locations?

We also had an issue that came up with sharing, and when and how to share the work that was being done. In some contexts, sharing the maps right from the beginning while the work was going on, offered the other students inspiration and encouraged them to complete their work on time. But in other instances, students were shy to share their unfinished work, and even sharing completed work seemed risky. Like with any social media, there are risks and implications, and those aspects of the project came up suddenly, and we had to make adjustments accordingly.

Would you do it again?

Yes, we are looking forward to doing it again next year. For one thing, we want to look at the overlap between students’ work. For example, all future students who choose to read one work can now see the previous work of other students, including their reactions and interpretations. Though again, we might need to rethink this aspect and maybe get permission from certain students, etc.

Another thought is that we find a way to represent all our ‘reading circle books’ so that they are charted on a single map. Perhaps this could be used to offer choices even before reading, or as a way to share experiences while and after reading them too.

Finally, we also think it would be good to somehow integrate the idea of time as an extra layer to the project. We might have to get creative by possibly using colour to indicate time or by branching out with a timeline tool. Either way, the idea of time periods, and also of stories that take place over time, could be explored further.

Featured image photo credit: Paul Rombough

Note: The following English language Arts (ELA) sample Cartograf mapping scenarios, based on Heather and Ruwani’s project, are available now on Cartograf:

Take Me to Your Culture!

Map your Literature Circle Novel

Map your Author

Trace the Voyage of the Odeyak