September 30th is Canada’s National Day of Truth and Reconciliation. We encourage teachers and schools in Quebec to participate in local activities and create space in their school for students to demonstrate what they have learned.

As Truth and Reconciliation day is near the start of the school year, it’s a great launching point for ongoing projects and lessons. Lessons that can help a new generation of youth to understand the unjust history and impact of racism and discrimination on Indigenous peoples.

In the post that follows, you will find some curated resources to help teachers and schools take actions that contribute to reconciliation. You will also read three stories from LEARN consultants Ben Loomer, Stacy Allen and Sylwia Bielec about the different ways we as individuals came to understand the work of reconciliation as educators.

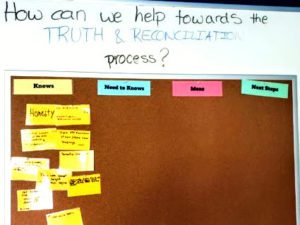

Pathways into reconciliation are as diverse as the people that engage in it. Before diving into reconciliation efforts, it is useful to identify your own history and the role it plays in relation to this work. You may want to have an honest dialogue with yourself about your motives, beliefs, and biases. One idea is to create a KWL chart to track your own progress and outline next steps toward becoming a more informed educator and ally. Knowing yourself and being aware of how your realities and privileges relate to others can help you to better understand where others are coming from.

To showcase, we would like to share our own pathways and reflections in regard to reconciliation work.

Ben Loomer

My pathway involves a few twists and turns but was very much influenced by Sabrina Bonfonti, a former colleague at LEARN. Around 2011, we understood that Indigenous students made up about 10% of the English School population and much higher in some schools and school boards.

Sabrina took the initiative to develop a strategic plan around Education for Reconciliation which included developing partnerships with organizations like Project of Heart. Participating classes learned about the Residential School experience and made art using decorated small wooden tiles to represent their learning and communicate their awareness. You can view a powerful video created at the time using the work of participating students in Quebec.

I learned a lot from teacher leaders like Lisa Howell (WQSB), who worked with her students to understand the work of Shannen Koostachin, who believed “that all children deserved to go to a good school”. Students at Pierre Elliott Trudeau Elementary School (WQSB) advocated for Shannen’s Dream – the belief that all students have a right to quality access to education in Canada, no matter where they live. It taught me that young people do not want to be passive in the face of injustice.

It was around this time that the Truth and Reconciliation Commision on Residential Schools was doing its work that Calls to Action were made including #62-#65 specifically on Education.

These include:

- Developing and implementing learning resources on Aboriginal peoples in Canadian history, and the history and legacy of residential schools.

- Sharing information and best practices on teaching curriculum related to residential schools and Aboriginal history.

- Building student capacity for intercultural understanding, empathy, and mutual respect.

- Identifying teacher-training needs relating to the above.

To an extent, curriculum resources and information on best practices have been developed over the last few years. We encourage teachers to use these resources in the classroom and communicate where more support is needed to have the impact necessary. LEARN has created padlets in English and French that include curated resources.

The ongoing conversations about the legacy of colonialism and residential schools with teachers and students – clicked personally with my own heritage of growing up Jewish in Western Canada. In my guts I understand the importance of language, culture and religion as core to identity and who I am as a person. I get the importance of teaching and learning and the transmission of history and heritage through family. So, the fact that children were taken away from parents, language and religion were suppressed, assimilation was an explicit goal. Homes and connection to land were taken. I recognize the injustice and the tragic impact of generational trauma and discrimination.

Knowing this, I reflect that Canada, a country of refuge for my ancestors was built upon racism, discrimination and stolen land. What is my responsibility now?

Stacy Allen

I am a white Canadian. I grew up in rural Nova Scotia on the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq people. Throughout my childhood, I was taught little about Indigenous Peoples in Canada. What I did know was limited to biased history textbooks and the banter of fishermen at my grandparent’s boat shop. It was not until I had completed 6 years of university and was teaching in Shanghai that I had the opportunity to attend a recruitment presentation for Cree School Board. During the presentation, I realized that I knew more about some of the cultures abroad than I did about the different Indigenous Nations in Canada.  I wanted to fill these gaps in my knowledge and learn more about why these gaps existed. This desire to learn led me to a job at Kativik Ilisarniliriniq School Board.

I wanted to fill these gaps in my knowledge and learn more about why these gaps existed. This desire to learn led me to a job at Kativik Ilisarniliriniq School Board.

In Nunavik, I worked and learned with some genuinely fantastic Inuit educators, students, and community members. These relationships taught me about some of the politics and injustices surrounding Indigenous education, health care, and housing. It made me realize how privileged I was to grow up with constant access to clean water and services in my first language.

I had attended schools with same-race teachers and a curriculum that aligned with my family’s values and ways of knowing. My Inuit students did not have these same privileges. Sure, there are no more ‘residential schools’, but every day many Indigenous students still find themselves in eurocentric classrooms where they do not see themselves reflected in the teaching staff, curriculum content, or pedagogical approaches. I believe that all students would benefit from an education system with diverse educators and knowledge systems.

My Indigenous friends and students are what motivate me to continue to learn about the diversity of Indigenous Nations. They also inspire me to encourage other non-Indigenous educators to listen and collaborate with their local Indigenous communities. There is so much to gain when teachers and students work with the community and connect to the place where they live. The school and Kuujjuamiut ( people living in Kuujjuaq) worked together on ways to nurture students’ use of Inuktitut, connect students to Elders, and engage in cultural activities on the land. It was beautiful to work with the community on mutually beneficial projects. When schools and communities come together, not only is student learning enhanced but support networks and relationships are strengthened. The whole community benefits from increased communication and respect. To me, relationships are central to reconciliation; they guide my path. I believe that listening to stories and experiences helps deepen understanding and prevent current and future injustices and microaggressions.

So, what’s next on my path? While there are many different trails to explore, I definitely plan to attend more public events offered by the 11 Indigenous Nations of Quebec (like the McGill 21st Annual Pow Wow that will take place this Friday in Montreal). I hope to meet more people, celebrate the accomplishments of communities, and stand alongside them when they desire support. Since Covid restrictions have calmed down, I am also looking forward to finally getting out of the house and doing some day trips with my family. I plan on checking out some of the activities and locations on Indigenous Tourism Quebec. I think it is important to support Indigenous-owned businesses in the province and create opportunities for my children to learn about diverse cultures and ways of knowing.

As far as my professional life is concerned, LEARN recently received a donation for the Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada from the McConnell Foundation that will be on loan to English schools in Quebec. I am excited to connect and learn with the schools and communities that want to use this resource to further their learning. We will be creating a digital tool to document the Atlas’ travel throughout the province to further connect communities. Schools will be able to share how they use the Atlas with their local Indigenous communities. I think this will be a wonderful way for students and teachers to learn more about the 11 Indigenous Nations in Quebec.

Sylwia Bielec

On the day I write this, I am coming off a half-day PD session with teachers from the Cree School Board. We have been working on the implementation of a Cree History course for Secondary 3 and 4 that is now in its third year of experimentation. Some social science teachers at the Cree School Board are Indigenous, and a few are Cree, but most are not Indigenous. What they all share is a sense of purpose when it comes to teaching history to Eeyou youth, specifically a version of history long suppressed, often whitewashed, and too often unknown even by those born and raised here. For me, working as an instructional designer with Indigenous scholars and pedagogues on the History of Eeyou Istchee course has been a labour of love as well as a graduate-level education on how Indigenous issues are playing out in our society. I still have so much to learn.

I certainly didn’t know very much when I started working with Cree School Board in 2013. Although I arrived in Canada with my parents as a child in the early ’80s, I did all my schooling in Quebec, in English but mostly in French. I cannot claim to have learned anything at all about First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people during my passage in school, CEGEP, or university. When the horrors revealed by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission came to light, I was fully confronted by my own ignorance of a very long and ongoing chapter in Canadian history.

Inside of a tipi in Eeyou Istchee (James Bay).

My colleague and Indigenous pedagogue Mona Tolley (from Kitigan Zibi First Nation) once said to me that working with non-Indigenous folks who are discovering Indigenous people and issues for the first time is like opening a door that people didn’t know existed and showing them what is on the other side – “look at all that is here” she says to them. She describes the reaction of non-Indigenous people seeing the door for the first time as two-fold: on the one hand, people are awed by the vast landscape that opens up for them through the door, and on the other hand, they are suffused with feelings of anger and guilt that they didn’t know this door existed all along. That it is in fact a door even older than the country we call Canada, a door as old as the relationship between the original inhabitants of this land and the settlers that came to colonize it.

We can do better. Imperfectly, maybe clumsily at first, we as educators can take steps to make sure that the kids grow up knowing about and engaging with the issues facing Indigenous people today. The stuff we didn’t get to learn at school. After all, Indigenous issues are Canadian issues. We don’t have to be stellar at it at this stage, especially if we are just learning ourselves, but we do have to make a start in our classrooms. Indigenous scholar and elder Dr. Emily Faries said to our working group at Cree School Board that we didn’t have to “make the best thing, just the next thing”. Meaning that we didn’t have to be perfect, we just had to be better than whatever the last iteration was.

What will be your pathway into reconciliation, into honouring Indigenous voices in your classroom? For me, it has been my colleagues and my work, but I have done a lot of learning on my own along the way. A good place to start would be with something that you personally feel strongly about or are interested in.

I like reading, and books, so I gravitate towards those. I’m also a dancer with a strong folk-dance background, so I love to see Indigenous dances online and at pow-wows like the ones local to me in Kahnawake and Kanehsatà:ke (find all of them on the Pow-wow Trail page). I love to listen to podcasts when I walk, so I’m subscribed to The Secret Life of Canada. Yes, it’s just as spicy as the name suggests.

Good places to start

My go-to place for Indigenous books for students and adults

Good Minds https://goodminds.com

Current coup de coeur for teens: This Place: 150 Years Retold

A list of curated resources for the four Arts subjects: Music, Visual Arts, Drama and Dance:

Indigenous Resources for Teaching and Learning in the 4 Arts

https://padlet.com/sbielec2/1eefx6ksjkdo6h9l

NFB We Were Children

Resource for your own education, not for children younger than 16.

https://www.nfb.ca/film/we_were_children/

Historica Canada