As we launch into a new school year, we have high hopes that the pandemic is in our rearview mirror. Students have returned to school in person, and classroom strategies are readjusting back towards a semblance of normalcy. But, we have all changed in some way. And, in most cases, we have grown in terms of our skills and our practices, especially with regard to our awareness and use of available technologies for presentations, research, and even creative and collaborative work online. I think most educators hope to carry forward much of what they learned, and to find a way to, at the very least, keep their technological muscles toned while moving forward.

In November, I will be presenting to teachers and other consultants at the Collaborate, Create, Innovate Conference (CCI) in Laval, where the conference’s goal is to use the technologies that “became synonymous with isolation and separation…to foster a sense of reconnection between teachers and learners in a post-pandemic world.” Somewhat ironically, I will be delivering my first in-person workshop session in years. What I hope to accomplish in my session is to do more than just help teachers and consultants flex some of those new-found technical abilities. I hope to consciously and visibly alternate our learning process in the session itself, by including examples of how we learned to work and collaborate online, and how those same tools and strategies could be adapted to in-person or perhaps hybrid settings in a classroom.

The topic of my workshop at CCI is How to use a Design-Thinking process when building Games & Game-based learning strategies for use in the Social Sciences, which is actually something we have developed to a great extent on our Elementary Games and Game-based Strategies page. And the particular emphasis I want to stress in my workshop is how we (i.e. participants, but also students!) could work together and collaborate during each of the various stages of designing a game.

My session will also model a fairly generic inquiry learning process: one that includes learning phases like Engaging students, Exploring further, Investigating (through research), Creating, and Sharing back. (See the previous article on Social Sciences in a Digital Age!).

And what is more, having recently experimented with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) methods, and having created a template to help in my lesson planning (see my video UDL in a Social Sciences Learning Process), I will also design learning phases that consider those UDL guidelines: Accessing information, Building knowledge, and especially of providing different environments for students to Act and Express their knowledge.

I am still in the process of planning and building for this workshop in November. In this blog entry, I will show you some of my thought processes as I plan some of the learning activities and strategies.

Would you like to follow along as I set up the session, in its various stages and complexities! Are you game?!

Engagement, through a Collaborative Empathy Process

The goal of my CCI session is to show how teachers and students could build a game. In order to start the design process, we should first consider those future users, those future gamers. It’s much like we do when writing, or during other creative processes, where one often talks about audiences, as a way to understand how or what exactly to write or create. The target users would be other students in the same class. (Though you could imagine that games could be created for parents, elders, the community, etc.).

In most examples of Engagement phases in lessons I created for LEARN’s History materials, I had suggested methods like image analysis, or emotionally reacting to an image or story. In the design-thinking process, Empathy with the users of your “product or service” is also key.

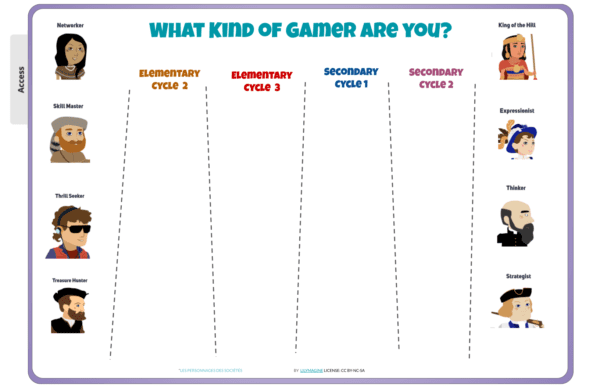

There are many strategies available to help guide students to empathise with others. As a simple way to get to know each other, I intend to show the group some of those typical “types of gamers” drawings, that are found on sites like GameRefinery’s Player Motivations & Archetypes, or possibly some from Media Studies – Different types of Gamers | Teaching Resources. It might depend on the group. One could also imagine using some of the more comical “types of students” drawings that you might find in cartoons from Farside and the like. (Ex. 1, Ex. 2, Ex. 3) The plan is to have each participant choose the type they are, in order for people to identify and categorise themselves, their styles, etc..

I am considering displaying those illustrations on a large visible space, but also I want a digital version to be available. So, I will use a high-resolution Google Slide/Drawing that participants can simultaneously access on their computers.

I am going to make the introductory activity more active, tech-friendly, and collaborative, like this: Participants will choose their own type-image (an avatar for a gamer type). They are then asked to drag a copy of that type-image over and into a specific area of the slide that corresponds to the grade level they teach. Next, they are invited to initial that drawing/avatar/caricature, so as to essentially reveal how they see themselves. In effect, they would be collaboratively building a portrait of the room, of our audience for the day, of us. A discussion (or online group chat) would follow, whereby people might identify common or more popular traits, to better know what kinds of games to build later.

Note how the strategy I brought forward from teaching online was that of using a common slide/drawing in Google. Also note that participants would then work together in that digital space, even though we will be in person. I intentionally designed that slide deck and the images inside it to be

1) large enough to be able to both print into a poster, or

2) to be able to cut up individual pieces to create smaller cards that could be played on tables in person, i.e. to play unplugged/offline.

I am making my process transparent, for this stage and for every stage, to help participants be conscious of what I am doing and to see there are various choices being made, and that other options are still available. I am intentionally preparing each phase of this lesson for it to be played out either online OR in class. Similarly, materials and methods are consciously being created to be flexible, so that they could be used in different formats to allow for different types of users requiring different forms of representation. If you have followed a few links above you would know by now that I created a so-called UDL Template to help me plan lessons in these ways. Here is what that introductory phase of my session looks like if written up in that template! (View in separate window)

Explore further… Define the Problem, Consider the Constraints.

“In the Define stage, you synthesise your observations about your users from the first stage, the Empathise stage.” (Source: interaction-design.org) But what problems do we have here, and is it just about our observations of our audience? I tried to use this kind of language when thinking about what to do next. How to explore further what’s available, while at the same time learning about our audience and their very specific needs.

First off, the participants/students have ‘personal needs’, to be engaged and entertained. The kind of games one would want to make for your class, or with your class together, need to consider these ‘personal needs’ of your users. So it makes sense to allow for time to browse and maybe even play a few existing games, to see if participants find them fun and interesting, and if they think their students would enjoy and benefit from them too.

However, I also want participants to consider physical and technical constraints, like, what strategies and materials are achievable, and, of course, can they be played online if needed? The game designs we would eventually come up with “should have sufficient constraints to make the project manageable.” (Source: interaction-design.org). That said, I also want to make it apparent what parts of our programs they are covering, (i.e. Program Content, Intellectual Operations, Competencies, etc.) and what academic goals are we trying to achieve?

And finally, we will also consider varying the materials and the gameplay to account for different student abilities. This can happen by including prompts to urge people to consider how the game on display could be played differently.

I know that all of this might not happen, not consciously anyway, in the space of only about 30 or 40 minutes of active exploration time, but I wanted all those elements to be there should individuals choose to go there. I suppose allowing for time and space to wander and wonder is part of how the whole process is “student-centered” in nature. I want participants to adjust the exploration experience to their own needs. To try things out and to make connections.

Stations seemed the only way to go. And so I plan to build five or six stations where people can spend a few minutes at each station learning how a specific game-type works. It will be apparent that different technologies were used to both create and play each game. And if they are looking for it, participants will be able to see how each game covers specific program content (i.e. a society for Elementary, time periods and social phenomena for Secondary) and even practice specific historical skills (i.e. each game usually focuses on one or two of our so-called “intellectual operations”). Each station will have a video that includes an explanation of the game with a demonstration, with links to the digital (and printable) instructions, resources, and tools.

That’s going to be a ton of work to create, right? Yes, but in a real classroom setting a similar process could take several days to tour, glean and benefit from each station. In class, each station could be a different game but also different course content covered. And after students are exposed to so many ideas, hopefully so many more ideas would germinate into projects. The ideal being your time spent designing the stations for exploration would be returned fivefold in terms of learning, technology practice, and interacting. In any case, for the purposes of my workshop, it’ll be enough to let each person get a feel for what is possible.

[Update: Since writing that last phase, I have already modified it in my planning tool here, in favour of a three station: Teacher, Individual learning and Practice model!]

Investigate, Gather, Process: Let’s just Ideate, already!

To put it into teacher language, let us remember my ultimate goal for this whole unit, for this whole learning situation. At one point my ultimate goal for the session was to actually have participants start making a game they could use and play in class. However, I quickly realised that that was unachievable in the short time I will have. So, now I am hoping participants can at least come up with some ideas for games that could work in their classes. Maybe a bit more than that. I want them to actually start to think about how the game might be played, to imagine then discuss it together, and at least note down a first draft, a prototype. I want them to Ideate. (Maybe they will build the game for homework!)

“Ideation is the process where you generate ideas and solutions through sessions such as Sketching, Prototyping, Brainstorming, Brainwriting, Worst Possible Idea, and a wealth of other ideation techniques. Ideation is also the third stage in the Design Thinking process.” (Source: interaction-design.org/)

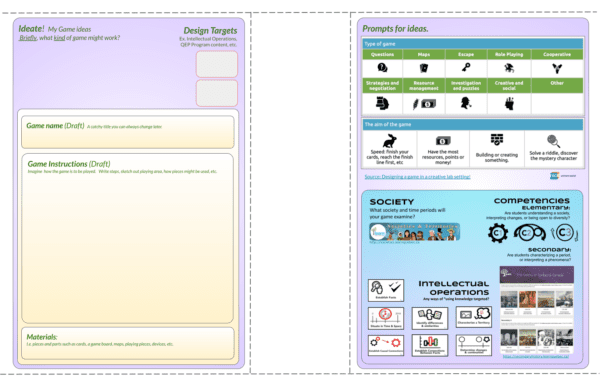

Again, for this phase of the process I want strategies and tools that are flexible and could be used both digitally and in class. I intend to provide examples for them to investigate and choose from. I want to use platforms that are varied: A Padlet for example ideas, a few Google Docs that I will present as printed lists with examples of games that could be adapted for the social sciences. In some versions of a series of game-design planning tools I created, I did have some example program targets (i.e. design constraints) that were suggested (Elementary, Secondary), but since we will be moving quickly at this point I will just remind people to try to keep them in mind. I want them to freely brainstorm ideas, but I also want them to come up with something concrete.

I felt that a simpler scaffolding tool might help, to remind them of some of ways games are typically played. I borrowed some terms from a template by RECITUS for game building, and I came up with a very compact exit-card-style design. (Yes, it looks like a card, with a back and front!) Onto this card participants could eventually scratch out their ideas with point-form game instructions!

How might they work collaboratively then? My plan is to have teams or partner-groups organised around subjects and levels. The first step would be for everyone to throw out a few ideas for a game that they feel would be doable, and that could use the content available on LEARN’s two websites, and lastly, that focuses on at least one intellectual operation. Then, together and as a team they are to choose and then commit to one idea. They must note it down on the exit card, and even briefly jot down draft instructions (i.e. come up with a prototype).

As you can see, that note-taking space I came up with is, again, a Google slide, so of course, this process could be done online. And yes, the card has prompts for certain participants/students to use if they need them. And yes, the process is collaborative, in that they must (and can online) all work together to create the single exit ticket idea to share back.

Will any of this work? We are pretty tight on time, so maybe this learning phase strategy will crash the first time around. But eventually, I believe that anyone can learn to think quickly and to ideate and formulate and construct ideas together, especially when the real work of finally building begins.

Collaboration means ultimately building something together!

What will the participants do with those exit cards containing each team’s idea? Before they go, there will be one last collaborative building effort to share with the whole group. Using another platform often used during the pandemic, to collect, display, share, and to learn, I hope they will can help organise them onto our growing Padlet of game ideas! The collaborative building activity for us, will simply be to get those ideas up in a common digital platform. Hey, did you know that you can post pictures of those hand-written cards directly from your phone’s camera to a Padlet? I didn’t, but you can bet it’s why I designed the cards in the way I did! And, remember, if it can be displayed on a computer it’s good to go for use on Zoom. And if it can be printed and cut out, there’s always the corner table for teams to hide away, learn, and play.

If I come out with a few ideas and thoughts on the effectiveness of the games LEARN has already produced or shared, I will be happy. And if people come up with an original idea or an adaptation of an old idea on their own, the goal I had for that phase of the session will have been met.

But ultimately designing something eventually leads to building something. In fact, that was always the ultimate hope for all the games on LEARN: that they (and the process used to build them) would serve as models, and that students would use the same tools online to collaboratively build and share their own games.

In this blog entry, I had very little time to go through the technologies we used for the games we built, but suffice it to say that anything available in the Google Suite is collaborative, from Documents to Slides to Drawings. Many other programs and software that are available online can be shared and made to work as a collaborative learning environment. (Ex. Minecraft, Cartograf, Prezi, etc.) Tasks can often be divided up easily using those same tools. Each participant/student could be assigned certain course content to research and then include in the project. Or each student might have certain building tasks that they do according to their own abilities. In turn, those same building spaces we used can also offer a place and a way to share back to the rest of the class. And sometimes even a place in which the game can be played!