Thank you to:

Katherine Davey (pedagogical consultant at Lester B. Pearson School Board)

and Annie Sabourin (FSL teacher at Beaconsfield High School)

for sharing your experience with us. It was a pleasure reflecting about choice together.

We live in a world obsessed with averages – from average sizes, to families, to incomes, to consumption levels. Averages are useful for analyzing data or establishing trends but they can also be used to design systems that are then applied to a large population. One example is the education system, which was structured as a one-size-fits-all model during the Industrial Revolution. In other words, the initial education system was designed for the “average” student, with the intent of mass education and preparing them for the jobs of that era. . Those rigid structures with a lack of individualization were developed for that specific context but today are criticized features in education. In his TED Talk, The Myth of Average, Todd Rose explains that there’s no such thing as an “average” student. Naturally, a classroom is full of students of different ages, backgrounds, aptitudes, skills, learning styles, passions and interests. And it’s no surprise that that one-size-fits-all approach isn’t effective in the classroom.

Dr. Shelly Moore

Dr. Shelley Moore, a Canadian ‘storytelling, inclusive educator, and researcher’, utilizes a bowling analogy to best describe inclusive education. When we aim for the middle to reach the most pins, it often results in a 7/10 split, leaving one pin standing on opposite sides. She further explains, “Professional bowlers do not aim for the head pin. They do not aim for the middle. They aim for the pins that are the hardest to hit…what if when we teach our students, we think not about our status quo middle of the pack or the headpin … and instead, we think, who are my kids that are hardest to get? What do I need to do so THEY get it?”. Aiming for the middle is a strategy to “reach” the most students, though what happens to those 7/10 split students, who might need more support, scaffolding or even more challenge?

One way of providing students with the best opportunities for learning and demonstrating their learning is by applying the Universal Design for Learning (UDL), regardless of specific student needs or abilities. The UDL framework encourages teachers to design activities and lessons that provide students with choices on how to engage with the content, how to access and interact with it and how to demonstrate and represent their understanding.

Fun Fact

The Universal Design for Learning Framework “was inspired in part by architects in the 1970’s and 80’s who began to design buildings that were accessible to all their potential future users by including access ramps, handicapped-accessible bathrooms, and curb cuts in the sidewalks right from the beginning, rather than waiting for complaints to inspire ungainly and unsightly retrofitting. It turned out that when they designed buildings for patrons who were “atypical,” the design worked better for everyone.” (Bray, Brown, Green, 2004)

Enter Choiceboards

How can we offer more choices to students? Providing students with choice boards (also referred to as learning menus) is a fun, engaging way of doing just that. In a nutshell, a choice board is a graphic organizer that presents different ways of approaching content and demonstrating learning and understanding. Offering choices aligns with the principles and foundation of UDL: “there is not one means of action and expression that will be optimal for all learners; providing options for action and expression is essential” (CAST, 2018). Examples of choices could be to create a brochure, a video, or a podcast instead of having all students complete the same end product. Having students choose the way they communicate their learning, among certain choices, increases their motivation and accountability, while at the same time empowering them as learners.

Katherine and Annie’s Journey with Choice

Lester B. Pearson school board consultant Katherine Davey had been pondering how to engage and support all students when Covid hit Quebec schools and all our students were online. As teachers adjusted to the rapidly changing landscape of teaching online, Katherine knew she needed to support teachers with some strategies that would keep the students engaged in their learning throughout the days online. Katherine explains, “I had in the back of my mind that choice boards [are] fantastic, but we need time…We need time to work with [different tech tools]. We need time to plan.” As with all abrupt pivots in life, time was harder and harder to find, so Katherine decided to offer a three-part workshop on exploring choice boards and sent the offer out to her school board. The spaces filled pretty quickly. High school FSL teacher, Annie Sabourin, jumped at the opportunity to further engage her students with one small tweak in her practice, “when you offer [students] choice, they feel a little more in control of at least one part of the project…because I always believe that giving them choices just makes them more engaged. And they feel in control.” Annie artfully explains that choice is a give and take – she still needs to cover the program, however, she can still offer “choice about the medium… [by trying] to give them different ways of doing your exercises.” For example, recording “a video rather than [doing] a Google slide.” Reiterating, “What works best for you?” to the student.

Image by Squirrel_photos from Pixabay

With all these choices, teachers might feel overwhelmed and have a sense of ‘losing control’, amongst the plethora of options, however, based on Annie Sabourin experiences with choice, “it’s all about not giving them too many choices at first, because if you give them too many, then they’re like, I have no idea what you do, Ms.. But if you give them just a couple and you make sure that they understand” what is expected, then their engagement level in the task increases dramatically. Keep in mind, when there are too many choices provided students can become overwhelmed and disengaged. Choice needs to be scaffolded and practiced for mastery of one’s selections to be successful. So what kinds of choices can we give to the students? Some common examples include:

- Different learning activities, such as reading a passage, watching a video, or participating in a hands-on activity.

- Different ways to demonstrate understanding or mastery of a concept, such as creating a project, giving a presentation, or taking a quiz.

- Different formats for presenting information, such as a written report, a poster, or a multimedia presentation.

- Different learning environments, such as working independently, with a partner, or in a small group.

- Different levels of difficulty or challenge, such as basic, intermediate, or advanced.

Overall, the choices included in a choice board should be diverse, varied, scaffolded and should allow students to select the option that best fits their learning style and needs. At first “most of them went to the easy ones,” Annie points out. This may be students gravitating toward what they’re used to doing. In those cases, maybe some choices need additional scaffolding to support students within their zone of proximal development. Over time with practice, students can learn about themselves and the choices they make and why.

After all, choice is a skill that one develops through making choices, and can actually get students learning more. Katherine recalls one teacher’s reflection who attended her choice board workshop, “One thing I remember her sharing with me is that once they were finished, they wanted to do it again. They just thought it was fun to choose things and the choices were engaging enough that they wanted to try some of the different ones. It was a way to demonstrate their understanding with respect to the separation of mixtures. So they enjoyed having that choice. They didn’t normally have choice in the classroom.”

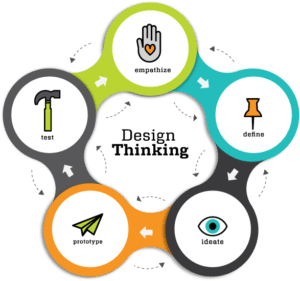

Designing for students

That first step in the design process is to empathize with who you’re designing the choice board for. It is essential to take this step slowly and to reflect on your students to determine the types of choices and different means being offered. And after all, they are the ones who will be using the choice board.

Who are they? What are their passions and interests? What technology do they have access to?

As Annie explains, “Groups change every year and I teach to a lot of different grades. I adapt to my students – what they like and what they don’t like. I’m always changing what I do. And my students are very athletic. So we talk a lot about sports, school, sports, and arts.” Empathy also caters to the students’ needs and interests, rather than supposed “averages” or generalizations.

Two Tips to Get You Started

Start small, but start. Getting to know yourself as a learner takes time, and making choices is something that takes practice. Start small by only offering two choices. Also, use templates that already exist. You can also recycle activities you’ve already been doing or search for online resources that already exist. To this, Annie elaborates, “It’s also about finding the right tools to make it faster for you to do. The other day. I made a choice board in 15 minutes. I think it’s just because I know where to find my tools now. At first, it takes a bit of time. I like very pretty Google slides, so I use a lot of slide media now with Alice Keeler‘s add-on.” As for resources, “I recycled a quiz, found a video… it takes a bit of time”.

In Conclusion…

The pandemic brought us lots of challenges without a doubt, however, it has forced educators around the world to think about keeping our students active in their learning process. As we have seen with choice, it might be one little tweak to our current practice that might just give the learning back to the student just a hair. As Katherine mentioned, this is not a new concept or strategy and in all likelihood, most of us have given choices to students to keep their involvement in their learning. We hope based upon the experiences shared in this blog post that we continue offering students some choice in our classrooms, in an effort to prepare these folks for a future yet to be built.

Resources

Padlet of choiceboard examples

CAST UDL Guidelines

Wakelet: A collection of resources about choiceboards

Bray, M., Brown, A., & Green, T. (2004). Technology and the diverse learner: A guide to classroom practice.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Kurt, D. S. (2020, August 18). Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development and scaffolding. Educational Technology. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://educationaltechnology.net/vygotskys-zone-of-proximal-development-and-scaffolding/

Photo credit:

Featured image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay