This is a collaborative post by Craig Bullett and Stacy Allen.

“Previous research shows that children as young as 4 years old can learn simple computer programming concepts (Bers 2007, 2012). These concepts draw upon and reinforce cognitive skills such as number sense, literacy, and creativity in young children (Clements, 1999). In addition to domain-specific skills, children who build a strong foundation in computational thinking competency can become more effective problem solvers and critical thinkers (Wing 2006).” – Bers (2018)

While coding and robots are a mainstay in many math and science classrooms, their potential to enhance language learning is often unexploited. Kindergarten and Cycle 1 teachers often feel pressure to help students transition from learning to read to reading to learn. Sometimes, this pressure leads to less time allocated to areas like science, social sciences, and digital competency; however, these areas can, in fact, peak student interest, increase engagement and enhance learning through cross-curricular infusion. In higher grade levels, teachers also feel pressure to prepare students for secondary and ministry exams. Class time must be used wisely because learning progressions pack a lot of content, and unfortunately, language teachers sometimes see robotics and coding as extras. This is a regrettable misunderstanding, as incorporating robotics and coding doesn’t reduce language learning time; rather, it enriches it by offering students practical, hands-on opportunities to strengthen and apply their language skills.

Language is all about understanding and communication, and coding provides an authentic opportunity for students to communicate and collaborate with others. When student groups are given a robotics task to solve, they engage in collaborative problem-solving and have the opportunity to practice classroom vocabulary, sentence structure, phonetics, and more. Even if the coding for the robotics task does not seem directly related to language outcomes, the task can ask as a situational problem where students have to use the language and communication skills they used to work together and also to explain their learning and thought process after completing the activity. Let’s look at an example.

At the Sommet du Numerique in 2023, we presented a concept for machine learning using Micro:bit. If you are not familiar with the Micro:bit, it is a microcontroller with various built-in sensors. The sensors can record data like movement, temperature, and light levels that can then be exported and analyzed by the students from grade 3 and up. You can learn more about using Micro: bit in your classroom with this turnkey site LEARN/RÉCIT created for teachers and students alike.

During the workshop, participants attached Micro:bits to various sports equipment, such as badminton racquets, baseball bats, golf clubs, and even foam toy swords. The collected data on two different movements and then “taught” the machine to distinguish between the two movements using the data provided. This activity was to teach students about data collection and how machine learning and basic AI systems, like Quick, Draw, can learn how to differentiate and sort data.

Not surprisingly, some Language Arts teachers struggled to make a connection to the technology because the activity did not naturally seem related to Language Arts. However, once participants began collecting their data it was clear that a connection could be made from the sheer amount of conversations that began happening in the room. It was amazing to see participants brainstorming together and asking each other questions about how to hook up the technology, how they made their movements, whether they needed more data or discussing what they could do to improve their model.

Teachers and consultants exploring screen-free robots for young learners

In many cases, it’s not about the technology, and in the case above, it is not even about the sports equipment! It’s about the dialogue and interactions that will occur naturally while students explore a new technology. Once you get over the hump of introducing technology to the students, the Language Arts aspects can flourish. The students may not even recognize that they are learning or practicing language while ‘playing’ with the technology.

Using robotics as an entry point for language learning, also works well with the youngest learners. Robots are great for free-play literacy centers because they are very open-ended. Earlier this week, my colleagues and I had the opportunity to present screen-free robots to preschool teachers at ETSB. During the morning, educators had the opportunity to explore about 20 different robots. In the afternoon, they had to make a plan for how they would use one or more of the robots in class for free-play. It was amazing to see how many educators made the connection to language and communication skills. Some activities involved having students navigate robots between Upper and Lowercase letters while practicing recognition and phonics, while others wanted their students to design and navigate obstacle courses with the robots to work on collaboration, or use the robots to sequence and retell stories. Each activity was paired with a list of vocabulary words, like left, right, up, down, code, pattern, repeat and plan. The teachers saw how robots could encourage students to practice communicating effectively to discuss ideas, give instructions, and troubleshoot problems.

Robots are a great entry point and there are many very simple robots that require next to no tech expertise to get started. There are also low-tech and no-tech options for coding and robotics. Many robots can navigate maps, like Kubo, Code and Go Mouse and Bee and Blue bots. You can customize these maps by adding letters, sight words, question prompts and more. Using the maps, students can complete different tasks involving phonics, writing, or reading. One of my favorite team activities for younger learners is to have one student say a letter phonetically and have the other student navigate the robot to the letters on the map. The students can alternate roles. They allow them to practice phonetics, computational thinking, and valuable collaboration and self-regulation skills for later in life. These activities can be easily adapted for older learners. For example, perhaps learners are given a mat with vocabulary words and/or definitions. They could code the robot to move between the points and then be asked to explain the connections between concepts or terms.

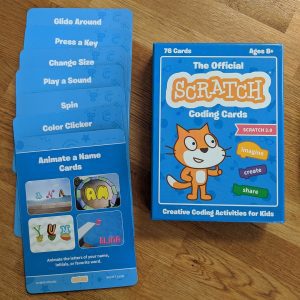

Many robots come with challenge cards or prompts students can pick from freely that are scaffolded for different levels. You can also find a lot of free task cards online like these Beebot and Scratch cards that work good for free-play and centers. Students can interact and direct fellow students using the skills and vocabulary from your language arts curriculum.

Scratch coding cards! Image source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/dullhunk/49729383778

Coding platforms and robots can also be used for storytelling and free play. Students can create costumes for the robots and navigate them to different locations. Starting with robotics can work well for some reluctant writers or when students need help deciding what to write about. They can print out a map with different settings and images of potential characters and then brainstorm their story with the robot before writing or recording the text. As an alternative, teachers could also begin with a story and have students remix or create their own stories using the plot or the characters as inspiration. Again here, students can plan with robots and then write or dictate a narrative. Students can record and share dictations quickly using the Chirp QR app; it is excellent for quick oral language assessment. Recording speech can work especially well for students who are anxious to present their work in front of their peers.

In addition to robotics, coding platforms and applications like Scratch, ScratchJR and OctoStudio are perfect for language classes. These two platforms allow students to quickly create animations using code. In these three platforms, the coding “script also runs as a sequence from left to right instead of the traditional top-to-bottom format of most adult programming languages, to reinforce print-awareness and English literacy skills (Flannery et al. 2013)” (as quoted in Bers, 2018). There are lots of potential ways to use these platforms in class; for example, students could retell or animate stories, create movie trailers for a book they read, advertisements for products they invent, or games. Students can then present their projects to the teacher or class, explaining their process, any challenges they encountered, and how they overcame those challenges. Moreover, many of these platforms are available in multiple languages, which makes them a good choice for students who are learning English or French as an additional language.

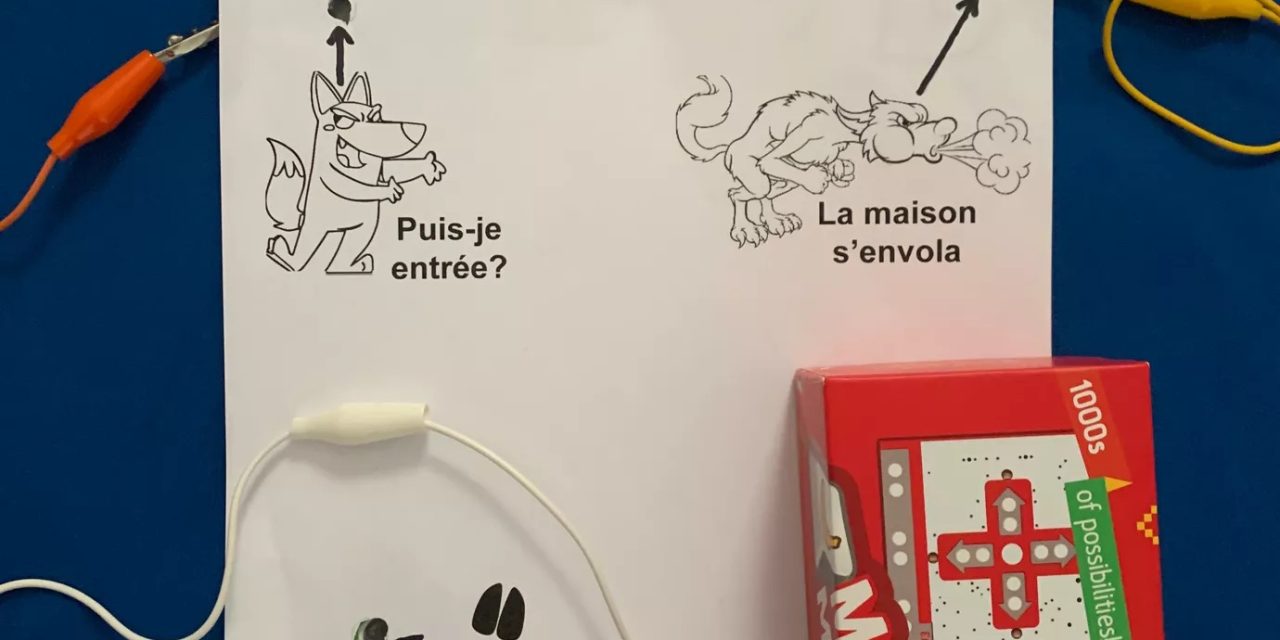

A Makey Makey can be attached to conductive material, like graphite pencil drawings. You can then use the Scratch coding platform to animate your creations when parts of your project are touched!

If you want to begin including robotics in your language class, LEARN and your local RÉCIT consultants are here to help! We offer free classroom visits. We can bring a few robots to your class and see which ones your students and you gravitate too or help you introduce programs like Scratch and Scratch Jr. If you are interested, you can fill out this form. We suggest starting small and working towards bigger and more creative projects. Coding is about so much more than just digital competency, it is about activating creativity, liking brainstorming and planning details, patterns, and elements and evaluating and editing the product until you reach a desired outcome. Coding is a language, learning languages alongside each other can prepare learners for engaging and interacting in an increasingly technological and global world.

Resources:

Bers, M. U. (2018). Coding as a Playground: Programming and Coding in the Early Childhood Classroom [PDF]. Retrieved on May 29, 2024 from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282538886_Constructing_the_ScratchJr_programming_language_in_the_early_childhood_classroom