by Melanie Stonebanks

My husband and I have spent years discussing and debating our perspectives and understanding of every aspect of the field of education. We met when we were in high school, and went our separate ways for a time being, reconnecting in our mid twenties. Our debates have ranged from which method of unit design is most effective to the covert predominance of white privilege that permeates the school system. We recently found ourselves revisiting one such discussion about my awakening to critical literacy, the result of it being the following post about the topic.

Lying around late one lazy Saturday morning in the Fall of 1998, a conversation on the topic of memories of elementary school and favourite childhood storybooks was featured. We had both attended elementary school at the same time and only a short two-minute drive between our respective institutions. We both spoke fondly of a visiting storyteller who captured our imaginations with his lively rendition of Robert Service’s poem “The Cremation of Sam McGee”. As our recollections meandered along to discussing our love of Roald Dahl’s classic “James and the Giant Peach”, I threw out how much C.S. Lewis’ “The Chronicles of Narnia” had me completely obsessed with the adventures of four British children in this fanciful land. Christopher gave me a sideways look, sighed and tightened his mouth (which I knew signalled that a serious discussion was about to take place).

What followed was an eye-opening shattering of my favourite childhood past-time; a dawning realization that I fought against that morning and many mornings after until emotion was set aside and thoughtful contemplation of this alternative perspective was allowed to be considered.

Christopher took no time in recounting an episode he had shared with a former girlfriend. She, an artist, had been hired to design a store window display based on C.S. Lewis’ “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe”. She had been sitting reading the novel (my favourite of the series) when she had asked Christopher if he had ever read the book. Christopher replied that he hadn’t but recalled it often lovingly described by many people as simply an endearing children’s tale. She then began to read passages from the book; all of which contained blatant and unmistakable Islamophobic language and imagery that depicted a whole race of villainous characters “The Calormene” simply born evil. Christopher recalled criticism of the depiction of Fagan from Dicken’s “Oliver Twist” denouncing the anti-Semitic overtones but was completely surprised that with such transparent and obvious demonization of people from the Middle East, that no one had ever spoken of it in these terms.

Looking back, I am embarrassed that it took so long for me to engage in a critical literacy discussion; and one that I did not initiate myself but was forced into kicking and screaming the whole way. It does make me wonder, that if not for my intimate relationship with this person from a background so distinctly different from my own, would I ever have contemplated the validity of an opposing “reading” of my cherished texts? Most probably not. I strongly believe that this form of personal connection is the catalyst to the majority of critical literacy awakenings in teachers coming from a White Christian upper-middle class upbringing like my own. It is not that we are evil people or bad teachers, it’s just that being constantly surrounded and reaffirmed by a homogeneous majority viewpoint does not promote the average person to question what has always been presented as the one way to see the world.

For many, it is sometimes easier to understand what something is not before grappling with what it is. I have used this pedagogical approach in my classroom when teaching my students about how to phrase an ethical question or the use of acceptable email and internet etiquette. This method can therefore be applied to one’s understanding of Critical Literacy. Comber (2001) assists us in our fluency by offering what reads as almost a heeding warning to professionals in the field

…it is not being negative and cynical about everything. It is not political correctedness. It is not about censoring the bad books and only reading the good books. It is not indoctrination. It is not developmental. It is not about identifying racism, sexism, prejudice, and homophobia somewhere else or in texts that have little relevance for readers. It is not whole language with social justice themes. (pp 271-272)

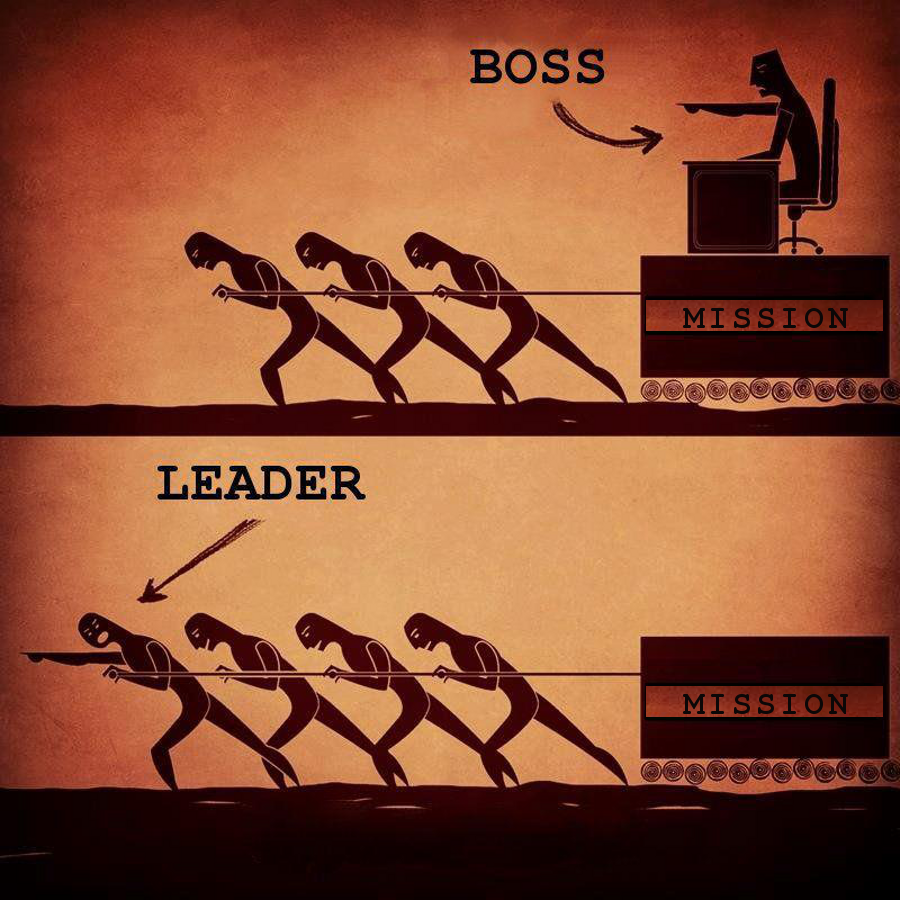

Margaret Meek (1987) writes about the importance of not simply teaching children to decode the words but to actually engage in dialogue about what the text means to them. It is much more than the technical acquisition of reading skills. It is through this active process of thinking critically and taking part in rich discussion with others that a deep and powerful comprehension of the reading unfolds. What stands out is the need for the readings to “have significance”, not only in the eyes of the teacher but in those of the student as well. They are equal players here; joint partners in the game where no one has the upper hand and each learns from the other.

Luke, (1997) describes Critical Literacy as a “commitment to reshape literacy education in the interests of marginalized groups of learners, who on the basis of gender, cultural and socioeconomic background have been excluded from access to the discourses and texts of dominant economics and cultures” (p.143). Critical literacy can be more simply defined as well as “the ability to read texts in an active, reflective manner in order to better understand power, inequality, and injustice in human relationships” (Coffey, 2008). In the elementary classroom setting, illustrated picture books, novels, conversations, songs, pictures, movies and the like are all considered texts. Central to critical literacy is the notion of dialogue around the texts, or in Freire’s terms, “reading the word” and “reading the world” (Freire and Macedo, 1987).

The development of critical literacy skills enables people to interpret messages in the modern world through a critical lens and to challenge the power relations within those messages. Teachers who facilitate the development of critical literacy encourage students to interrogate societal issues and institutions like family, poverty, education, equity, and equality in order to critique the structures that serve as norms as well as to demonstrate how these norms are not experienced by all members of society (Coffey, 2008).

Critical literacy is a way to use texts to help children better understand themselves, others, and the world around them. Using children’s literature, teachers can help their class through difficult situations, enable individual students to transcend their own challenges, and teach students to consider all viewpoints, respect differences, and become more self-aware.

There are many activities that are already going on in our classrooms that build critical literacy. Reading novels written from the point of view of a child from another culture or set in another country; sharing stories about families and their religious traditions or considering the lives of young people like them who lived through war, persecution or poverty; as well, when we ask our students to write from the point of view of someone else; all of these classroom experiences are ways of developing critical literacy. As Melissa Thibault (2004) reminds us, these activities all serve the same purpose: they help the student to see the world through someone else’s eyes, to learn to understand other people’s circumstances and perspectives and to empathize with them.

My next post in the series about Critical Literacy will forward many examples of how to actively weave this type of literacy approach into your classroom.

Melanie Stonebanks

References for further reading can be found here:

Coffey, H. “Critical literacy.” LEARN North Carolina, 2008. Retrieved from http://www.learnnc.org/articles/article?id=maples0601

Comber, B. (2001). Critical Literacies and Local Action: Teacher Knowledge and a “New” Research Agenda in B. Comber & A. Simpson (Eds.), Negotiating Critical Literacies in Classrooms. (pp.271-282). NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc.

Freire, P. & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the Word and the World. London: Routledge.

Luke, A. (1997). Critical approaches to literacy. In V. Edwards & D. Corson (Eds), Encyclopedia of language and education, Vol. 2: Literacy (pp. 143-151). The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Meek, M. (1987). How Texts Teach What Readers Learn. Gloucestershire:Thimble Press.

Thibault, M. Children’s literature promotes understanding. LEARN North Carolina, 2004. Retrieved from http://www.learnnc.org/articles/article?id=maples0601

Very interesting post Melanie. I really enjoyed it. It makes me miss teaching English even more. I always wonder about one thing though, and would like to have your response to my concern. It has to do with the the technique you mention of writing from the point of view of another culture, especially when that culture has been oppressed in the past. I have had my students do that even this year teaching history, but I am never sure of whether it is good practice, morally, politically, historically, etc., when for example I have a student from a white middle-class background try to write from the point of view of, let’s say, an Iroquoian or an Algonquian. In some ways they can imagine, understand and empathize, but aren’t the risks of perpetuating misconceptions and misrepresentations equally great?

Hi,

As a media education/literacy teacheer for 35 years I have been exploring what it means to be literate in the 21st century. My own rsearch suggests that we have to rethink what is literacy and illiteracy. This is vital if we are t understand how to exploit print and non-print literacy so that youth on the fringe of the education system can share in the full experience of learning not as a deficeit model may suggest but rather what they have to bring to critical literacy.

It is not that print literacy has lost its value and indeed is even more valuabke than ever before but we need to acknowledge that reading/analysis and writing/producing are valid in today[s clasroom.

I woul dlike to continue this conversation. PLase se my book the Struggle for Literacy. BTW this is not meant as a promo but rather as a passionate hope that all children can be included in the literacy experience.

Lee

I think there is also the issue of reading literature that represents the dominant culture critically. What is the author trying to say? How are we being manipulated? Sometimes starting with self (Oh I wish we had read Dick and Jane critically to see how the white middle class lifestyle was being shoved at us) and seeing how we are portrayed is the best way in to then thinking about how others are portrayed. We are fortunate now, that so many more books are available that are representative of other cultures and sub-cultures, written by people representative of those cultures and not by people imagining what it is like. Students have the opportunity to compare these portrayals.

And so many wonderful picture books that deal with issues… In so many places the gut reaction is to ban books that represent people in a bad light – everything from Mark Twain to Shakespeare (Merchant of Venice). Far better to read critically, to learn about the mores of the time, to consider why some people might find a text objectionable. Then, perhaps, as adults we can also read news with a critical eye for who is producing the text and why.

Thanks for giving us lots to think about.

As I looked back at my early education, I cannot seem to pin point what critical literacy was much less any activities which supported critical literacy. As I was reading this post, I came across two ways to look or define critical literacy. As sited from Margaret Meek (1987) “It is much more than the technical acquisition of reading skills. It is through this active process of thinking critically and taking part in rich discussion with others that a deep and powerful comprehension of the reading unfolds” this quote states exactly how I was taught to read – by learning the technical acquisition of reading skills. Furthermore, “Critical literacy can be more simply defined as the ability to read texts in an active, reflective manner in order to better understand power, inequality, and injustice in human relationships” (Coffey, 2008).” When learning to read, I can remember being told to read quickly and get the book finished. Now that I look back, perhaps if critical literacy was valued I would enjoy reading a great deal more. This could have easily been done through different teaching techniques and a multitude of activities. As stated in the post, “There are many activities that are already going on in our classrooms that build critical literacy…” and “these activities all serve the same purpose: they help the student to see the world through someone else’s eyes, to learn to understand other people’s circumstances and perspectives and to empathize with them.”

It seems like there are so many ways to define what exactly Critical Literacy is and how it can be developed in the classroom.

This post really outlines our current need for adequate critical literacy skills in our ever more multicultural and multifaceted classrooms. It is so important for children to, not only read a text and understand the content, but look at all areas of our world (through the news, the internet, novels, poems, etc…) and pinpoint what the underlying meaning is and how it affects or impacts them.

This posts describes about cultural literacy being a way “to help children better understand themselves, others, and the world around them.” To go slightly further, cultural literacy will also undoubtedly contribute to a greater and deeper understanding of the texts students engage with, thus increasing their academic success as well. Meaningful learning is the most effective form of learning, and if children can really identify with a text and what it means to them, they will certainly walk away with a greater understanding and appreciation of the text, rather than the student who only looks at the surface meaning of the content.

This post discussed some extremely important issues that are enormously relevant in the classrooms of Elementary schools today. We live in a multicultural world. To think otherwise would be unreasonable. This stands for our classroom and students as well. So why not have this be a topic of learning and progression, rather than one that is stepped around or ignored? Students are capable of more than some people think.

Melanie, you mentioned the idea of simply starting a discussion, a dialogue about a topic. This struck me most. No one is necessarily right, wrong, better or worse. This simply allows students to express their opinions, based on their own unique experiences, and furthermore, hear some alternate thoughts that are based on completely different, unique experiences of their peers. This simple act of expressing, listening and critically thinking could be a complete game changer for some students. If nothing else, having this kind of environment in your classroom is a starting point for your students to learn to be open and critical, as this will be required of them for the rest of their lives. Simple elementary literacy seems like a great place to start.

This was a very interesting read because it showcases the importance of encouraging students to think critically, not only in reading but as individuals as well. By creating a classroom environment that encourages our students to discuss their ideas, which will undoubtedly be very diverse, we are also developing students’ listening skills which is an extremely important element of a respectful environment and society. These types of discussions and reflections that incorporate diverse opinions will cultivate a rich learning environment as well as a more responsible society.

This article raises some interesting points about the cultural and societal norms that are being pushed through the use of novels we consider to be “classic”. Often, when we engage with these materials, we are aware of the differences between this time period and our own in very specific terms; for example, the technological differences, or the overt racial inequalities of the period. We are less critical when considering the more subtle racist language, like discussed here in The Chronicles of Narnia.

The result is that while children may be competent readers, they are often passive, simply letting the story wash over them rather than actively searching for meaning. While we may understand the importance of critical literacy, when faced with supposedly neutral, or non-political texts like the Chronicles of Narnia, we, as educators, must take the time to engage with this material from a critical perspective. Rather than simply accepting certain novels as “classics”, we must ourselves search for the underlying messages or themes so that we can bring these to light for our students.

I connected to this entry simply because I too enjoyed reading “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe” in elementary school. While reading this text, I realised that I also did not notice some of the thing you described in your entry about the book. This makes me realise that most of the time we are biased when it comes to things like these. For example, we enjoyed this book so much that we never thought to look back and be critical of the text. This is something I want to teach my students to do as an aspiring teacher; thing critically of the texts they read. When this happens, it completely avoids what you and I have experienced when realising the different side of the book we cherish so much. Of course, there is nothing wrong with enjoying the book and appreciating it, however being blinded is something I want to avoid when it comes to reading books and other texts. This can be achieved through critical literacy skills.

‘The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe’ was one of my favourite books growing up. In fact, I read it in grade two and it was probably “THE” book that turned me into a life long reader. So you can imagine the level of my devastation when I learned in my late teens that not only was it extremely religious in nature, but also extremely anti anything non-Christian. I re-read it as an adult and was horrified.

I adore the point you made about how it may be easier to understand what something is not, before you can understand what it is. What a great tip! Thank you!