My daughter recently had the opportunity to participate in a Genius Hour project at her school and then a board-wide sharing session, where principals and vice-principals met students from around the OCDSB to hear about their Genius Hour projects. My daughter’s math teacher, Chris Hiltz, introduced this initiative at his school 3 years ago, and has become an ambassador for the project in his school board. I spoke with him about his Genius Hour experiences to date.

Name: Chris Hiltz

School/Board: Fisher Park/Summit Alternative, Ottawa Carleton District School Board (OCDSB)

Level: Middle School

Subject: Math

Experience: 15 years

What is Genius Hour?

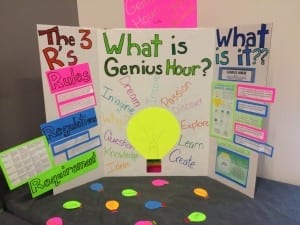

Genius hour is a movement that allows students to explore their own passions and encourages choice and creativity in the classroom. The teacher provides a set amount of time for the students to work on their passion projects. Students are then challenged to explore something that they want to learn about and to do a project about it. They spend several weeks researching the topic before they start creating a product that will be shared with the class/school/world. Deadlines are limited and creativity is encouraged. Throughout the process the teacher facilitates the student projects to ensure that they are on task.

http://www.geniushour.com/what-is-genius-hour/

Why was it important for you to introduce the idea of Genius Hour at Fisher Park/Summit Alternative?

CH: I’m getting the feeling, I don’t know if it is my age or how many years I have been in the game, that there is going to be a fundamental shift in what schools are. I’m not talking about revising the curriculum, or having more computers in the school. I think that in Canada, we’re going to have to take a hard look at what schools are, and at what they can be. The driving force for this change is access to the internet.

To tell a student that I am the holder of knowledge, and you have to learn what I say when I say it, is less and less accepted by students and by me! My role has to change as an educator. I need to think differently about what education is, and what this building is, for the students who come. I have been playing with this in my mind for a while, while hearing people like Ken Robinson, Daniel Pink, and Will Richardson talking about how things are changing in education.

I was on the lookout for something that could change in my practice, and my approach to teaching, when I came across the idea of Genius Hour a few years ago. It really resonated with me. I could see other teachers in my building being interested too.

It really did prove to be a great way to explore these ideas of how schooling can be different, how we can put more responsibility for learning on the students. Not that I am saying that I want to give away all of the responsibility to make my job easier, because it doesn’t, but to allow students to take the reins, and more control of their own learning.

Bringing in what schools are calling “21st century skills” (critical thinking, problem solving, collaborations, making more and authentic use of technology) is gaining more momentum in the education community. Universities are looking for these skills, but in the elementary grades we want to see these skills develop in our students as well. If we want students to think critically, we need to incorporate these ideas into our day-to-day work. Genius hour, I thought, was a great way to address or explore some of these ideas.

What was your timeline and, how did you introduce Genius Hour?

CH: Over a school break, I stumbled upon a short video, “What is Genius Hour?” Coming back to school, I went straight to my principal, shared the video with her, and I told her, “This is something that I would be interested in trying here. Do you think that I could try? Can I go to staff and see if there is anyone else?”

I got an immediate YES from my principal! In January 2014, I put an e-mail out to the teachers to gauge interest. Luckily, a couple of the teachers in the alternative program replied that they would be interested. We were able to get release time from our principal to sit and talk about what this could look like.

The video didn’t have a lot of answers so we spent some time doing research, finding resources, and talking about what this could look like at our school, what things might we adopt, what things would we have to create. We blocked six weeks in which we chose two 50-minute periods, times when our schedules could sync, to dedicate to Genius Hour.

We started our first Genius Hour the first week after March Break. We brought four classes to the auditorium to introduce the idea, how it was going to work, and how it was different from a “regular” school project. We didn’t ask how it wouldn’t work. We ran with it!

It ended up being almost instantly transformative for the teachers and students involved. It became very apparent that this was not a typical kind of project!

The first thing that we saw was the wide range of student interests. It took some thinking to get out of the rut of what a “regular school project” is, to try to push the students beyond PowerPoint and the science fair poster board. We had to unlearn or think differently about what this project could be.

Over those weeks, we extended our planned 6 weeks to 7.5 or 8, we saw that the students’ engagement was very high. Their problem-solving and research skills were being put to the test and they knew that they could rely on their teachers, and each other, to help. With our first sharing day, we knew immediately that this was something that we wanted to do again.

In the first year we started with four teachers and four classes. The second year, we had seven classes. In 2016, we had four grade 8 alternative classes, three early French Immersion grade 7 classes, the grade 7 gifted class, 2 core French classes, and a middle French immersion class, PLUS a music teacher ran a subject-specific genius hour project! It is gaining momentum in this school and in our district as well.

How did you start spreading the word in the district?

CH: I knew that I didn’t invent this idea. There are schools around the world using this idea. Luckily for us, we caught the attention of a few people, including Peter Gamwell, a superintendent in the district. He was really interested in what we were doing and it reminded him of things that he had seen in some other schools. We got great support from him.

With Peter’s support, we were able to secure a grant from the Ontario Ministry of Education to create a Professional Learning Network in the OCDSB for teachers interested in trying a passion-based project like Genius Hour. We love it so much, and it worked for us. We wanted to see others try it!

When we got that grant, it made it real for us. We started to get invited to leadership conferences. Last spring we were invited to present at Principal/Vice-Principal Leadership conference where we went with a prepared presentation and some students. Most principals coming into the building had never heard of Genius Hour before. The floodgates opened!

We started getting e-mails from all over the board. In our original grant we had ear-marked money to release 10 teachers and we ended up with over 30! Principals around the district wanted to pay for their teachers to be a part of the network. It quickly snowballed!

It made planning things a little more challenging for us. Our network met for the second time this April. The teachers, who had tried Genius Hour at their schools, gained some resources that we developed and shared some resources that they had. Our ultimate goal is creating an online resource kit that educators and classroom across Ontario could tap into to try something like this in their school.

The projects we love talking about: revealing a child’s hidden genius

One of them comes from the first year of our Genius Hour experience. It was not one of the students that I taught but this young lady was non-verbal until she was 7 years old. Through her Genius Hour project, based on fashion, she developed a mannequin that had a piece of clothing or an an accessory, representing every decade in the 20th century.

She presented her mannequin in front of all four classes, something that her teachers, or her parents, would have never thought that she would be able to do. The passion in this kid came out and allowed her to try something that was outside of her comfort zone, opening our eyes to the potential of this project.

Another example: there are always students who want to learn how to code. It’s an important skill to have. A student last year wanted to make a video game, but he had a different approach. His approach was, “I’m not going to make a video game that I want to play. I’m going to make a video game that my 4 year old neighbour wants to play.”

He interviewed his 4 year old neighbour and asked for some art work too. He took the scribbly drawings of the good guys and the bad guys and he used them to create a video game. In the process, he kept going back for feedback. He took a popular topic, creating a video game, learning to code, but he put an interesting spin on it by looking for a market. He really showed what he was capable of by adding that one extra question – how can my video game be different?

Can students choose their Genius Hour advisor?

We decided that Genius Hour works best when you give as much freedom as possible to the students. That includes the freedom of where to work in the building and to work with someone who you would not necessarily work with regularly. We decided to mix classes so that teachers would be in four different areas of the building: computer lab, library, a quiet work space with some wireless devices and a sewing machine, and maybe the cafeteria. We needed to keep track of where students could go, but the students had the choice.

At the beginning we looked for the emerging themes of the proposals. Some themes that are popular: technology (coding), engineering and building, and, for want of a better term, arts and crafts. We then divide the students, as equally as possible, into four groups, and each teacher is the advisor for a group, responsible for making sure that resources are available, that problem solving is happening, and keeping on top of the students’ progress. Students don’t necessarily work with the students in their class or a teacher that they know.

What are some of the challenges that you encountered?

CH: The trickiest part is the logistics at the beginning. Scheduling can be a nightmare! If a teacher wants to follow in our footsteps by syncing up classes and allow the students the freedom to work with different people and in different spaces, you have to spend some time with other interested teachers and their timetables.

If you have mobile computer labs, or a sewing lab, book those resources as early as possible.

We haven’t had to deal with challenges from students, or parents, or other teachers about why we are using our time on this. Parents could say that school is meant to be spent in class, or whatever misinformation parents might have. Lucky for us, we haven’t had to deal with that.

My advice: plan and schedule as much as possible, right from the beginning. The planning starts in September for a Genius Hour that might not happened until the spring.

What are some of the links to the curriculum that you have seen coming out in the genius hour projects?

CH: I see that what my students are doing is everywhere in the curriculum. The easiest ones for me to see are in the Language curriculum: asking rich questions, research skills, assessing the credibility of a resource, oral presentations.

Also, it was not hard for me to spot the math in the projects. Last year, a boy in grade 8 was really into Rubix cube. His question was, “How long would it take to go through every combination on a Rubix cube if you could change to a new combination every second?” The amount of math that he did was literally astronomical because he tied it into how long it would take for our sun to die. It’s that many!

Straight out the curriculum: conversion of measurement units, of time units, sophisticated mathematics including exponential notation, scientific notation, to express these massive numbers, and even things like using ratio and rate. He figured out if he could do so many turns in one day, how many he could do in one year, and then figure out how many millions of years it would take him to go through all of the possible combinations. It was not hard for me to see the math!

He could come to a teacher to find out how to do all of these things. It would become a conversation with him and the teacher. Instead of the teacher saying “let me teach you how to do it,” the student goes to the teacher and says, “I need to know how to answer this question, and I don’t really know where to begin. Can you help me out?”

Another great example: A grade 7 girl this year is really interested in baking. She decided that she was going to follow a recipe, but make the recipe for 200 people, using ratio and proportional reasoning, directly out of the grade 7 curriculum, to make a recipe bigger.

DC: That project was multi-generational as her parents and grandparents worked with her. Some of the projects become family projects.

CH: Great story! That family spent the entire weekend in the kitchen together. They had it down to a science: the assembly line of production. That level of engagement with school, to have an entire family on board, you don’t get that with a traditional project or homework.

What would be your Genius Hour project? Genius Hour has clearly been a passion project for you.

CH: That’s what I usually answer if a student asks: that Genius Hour is my Genius Hour! I am always looking for ways to improve and expand, to get the word out and see how we can do things a bit better.

Also, I am really interested in exploring new ways that school could be… things like scheduling. Does everyone have to do math at the same time in my class?

I would love the opportunity to explore that, to have the freedom to look at what tiny changes we could make in our building to make learning more authentic and meaningful to students. My role as a teacher is changing, and I have to be open to that change to best help out my students. They’re here for a reason: they want to learn. There are different ways, and maybe even better ways, that we can get that done.

I sometimes say that I have never met a child who is not gifted. But in our classrooms, we don’t always get the opportunity to uncover the genius in every child. Genius Hours seem to be a way of doing just that.

You can connect with Chris Hiltz, and follow along with his Genius Hour journey, on Twitter @mrhiltz .

Have you tried Genius Hour or other passion-based learning projects at your school? Share your experience in the comments below.

If only the Reform science program had been a “passion-project” of its architects. They would not have created a minestrone.