In his 2006 Ted Talk, Do Schools Kill Creativity?, the late Sir Ken Robinson, famously proclaimed that “creativity now is as important in education as literacy, and we should treat it with the same status.” He defined the term as, “the process of having original ideas that have value — [it] more often than not comes about through the interaction of different disciplinary ways of seeing things.”

In education, it is often said that we measure what we value. Someone must have been listening from the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), the body that creates the Programme for International Student Assessment. Their upcoming PISA 2022 will focus on mathematics, science, and reading, with the addition of an innovative domain on creative thinking. What!? You might be thinking – Don’t we have enough tests already? Now, we’re going to crush children’s creative spirit by trying to measure it!

One common pitfall is that creativity is often confounded with artistic ability. When people say that they are not creative (we hear this a lot), they are likely expressing their beliefs about their own lack of artistic talent. But, in this case, what we are referring to is creative thinking, which is more akin to generating original ideas and experimenting with different ways of doing things, as described below.

In the PISA 2021 Creative Thinking Framework, creative thinking is defined as “the competence to engage productively in the generation, evaluation and improvement of ideas, that can result in original and effective solutions, advances in knowledge and impactful expressions of imagination.” While the OECD’s Strategic Advisory Board defines creative thinking as “…the process by which we generate fresh ideas. It requires specific knowledge, skills and attitudes. It involves making connections across topics, concepts, disciplines and methodologies” (p. 8). Since creative thinking is applied in a variety of contexts, the PISA assessment tasks will focus on 4 domains – creative writing, visual expression, scientific, and social problem-solving. I will address these more specifically in my next blog post.

In the PISA 2021 Creative Thinking Framework, creative thinking is defined as “the competence to engage productively in the generation, evaluation and improvement of ideas, that can result in original and effective solutions, advances in knowledge and impactful expressions of imagination.” While the OECD’s Strategic Advisory Board defines creative thinking as “…the process by which we generate fresh ideas. It requires specific knowledge, skills and attitudes. It involves making connections across topics, concepts, disciplines and methodologies” (p. 8). Since creative thinking is applied in a variety of contexts, the PISA assessment tasks will focus on 4 domains – creative writing, visual expression, scientific, and social problem-solving. I will address these more specifically in my next blog post.

It is thought that by having students work on more than one subject, “it will be possible to gain insights on country-level strengths and weakness[es] by domain of creative thinking” and “uncover the extent to which students are encouraged to search for their own solutions and ways to express their ideas.” This might also provide important data on how creative thinking should be taught across different disciplines.

In addition to these assessment tasks, students will be given a background questionnaire that will provide information on different drivers of creative thinking and factors that are not assessed in the test. These will include scales that measure their general curiosity, openness to new ideas and their disposition for exploration, as well as questions related to students’ confidence in their ability to think creatively in different domains. Students will self-report about their beliefs on creativity – whether it is innate or can be developed, whether it extends beyond the arts, whether it is a positive thing to be creative. They also be asked about the types of activities that they do in school as well as their out of school experiences.

Perhaps, the OCED’s thinking is that, in fact, we value what we measure. According to the PISA 2021 Creative Thinking Framework draft from April 2019, in developing the creative thinking assessment, the OECD hopes that it can “encourage positive changes in education policies and pedagogies” by providing “policymakers with valid, reliable and actionable measurement tools that will help them to make evidence-based decisions.” Furthermore, they believe that “the results will also encourage a wider societal debate on both the importance and methods of supporting this crucial competence through education.”

Indeed, the debate has already begun before the results are collated. When this 21st Century Skills innovative domain measure was announced in 2019, Ireland and Wales, who regularly participate in the mathematics, science, and reading assessments, had already decided to opt out of the creative thinking portion of the PISA. According to the website for the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada, all 10 Canadian provinces will be participating in the full PISA, while others will also include a component on Financial Literacy. This isn’t surprising since Canada tends to score well internationally on the PISA.

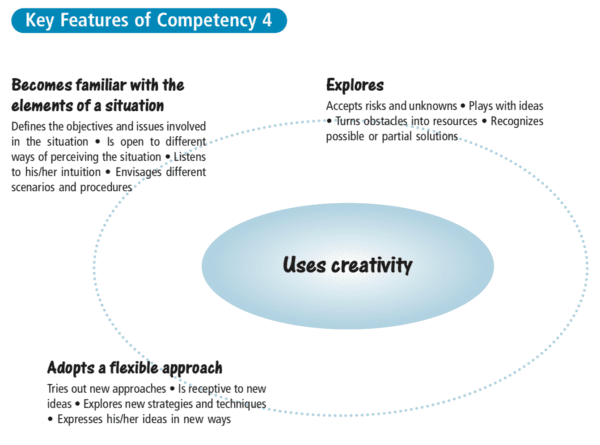

Students in Canada, and more specifically, Quebec, should be well prepared for the creative thinking component. The Quebec Education Program has included “Uses creativity” as one of the Cross-Curricular Competencies at all levels of Elementary and Secondary education since it was first rolled out in 2000.

For example, the Secondary Cycle 2 program is in line with what is defined in OECD’s framework, as it describes the competency in the following way:

Creativity is by no means limited to the arts, with which it tends to be associated, but plays a role in all areas of human activity…Being creative consists essentially in using the resources at one’s disposal in an original way.

More recently, “Creativity” has appeared as one of the “6 C” competencies in Michael Fullan’s Six Global Competencies for Deep Learning (NPDL) in 2014. Many of our schools have been working on implementing the model in the classroom, so this “C” will certainly be familiar to them.

Another sign that we value creative thinking in Quebec is the Ministry of Education’s Digital Action Plan, which includes a Digital Competency Framework that comprises 12 Dimensions, the last of which is Adopting an Innovative and Creative Approach to the Use of Digital Technology.

The PISA Framework suggests that for some educators, developing students’ creative thinking skills seems to involve taking time away from other subjects in the curriculum, but in reality, students can apply their creativity across subjects. The Cross-Curricular Competency chapter in the Secondary Cycle 2 QEP document emphasizes that:

At school, all the students’ activities should foster creativity. Consequently, the school should provide learning activities that encourage students to use their personal resources, devise problems with more than one solution and situations that stimulate the imagination, and promote the use of a variety of approaches rather than one standard approach.

While the program tells us what we should be doing, it doesn’t necessarily illustrate how to implement these tasks in the classroom. What seems clear is that if we say that we value creativity but our practices do not encourage it, the competency remains but a model on the pages of the program documents.

If students have these opportunities throughout their elementary and secondary school education, we could assume that they will be highly successful at the types of tasks presented to them in the PISA test. If students haven’t had opportunities to practice divergent thinking and idea generation, they just might stare blankly at the screen when the PISA tasks are presented to them. This might explain why some countries are reluctant to participate in this component of the assessment. I remain optimistic that the results will provide some insights into where we collectively have some work to do.

The Creative Thinking PISA assessment emerged from another OECD project that aimed to support new pedagogies that can foster creative thinking. OECD’s Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) led an eleven-country action research project on ways of teaching and assessing creative and critical thinking which they claim provided encouraging results. In my next post, I will explore some of the findings, and what we can learn from them.

References

CERI. Fostering Students’ Creativity and Critical Thinking – What it Means in School.

https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/fostering-students-creativity-and-critical-thinking_62212c37-en#page8

CMEC. PISA 2022.

https://www.cmec.ca/712/PISA_2021.html

Fullan, M., Quinn, J., & McEachen, J. (2018). P.17. In Deep learning: Engage the world, change the world. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, a SAGE Company.

MEQ. Digital Competency Development Continuum. P.32.

http://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/ministere/continuum-cadre-reference-PAN-en.pdf

MEQ. Quebec Education Program – Chapter 2 – Cross-Curricular Competencies p. 23.

http://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/education/jeunes/pfeq/PFEQ_competences-transversales-primaire_EN.pdf

MEQ. Quebec Education Program – Secondary Cycle 1, Chapter 3, p.42.

http://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/education/jeunes/pfeq/PFEQ_competences-transversales-premier-cycle-secondaire_EN.pdf

MEQ. Quebec Education Program – Secondary Cycle 2, Chapter 3, p.42.

http://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/education/jeunes/pfeq/PFEQ_competences-transversales-deuxieme-cycle-secondaire_EN.pdf

OECD. PISA 2021 Creative Thinking Framework (Third Draft) April 2019.

https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA-2021-creative-thinking-framework.pdf

Robinson, Ken. (2006). Do schools kill creativity [Transcript].

Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ken_robinson_do_schools_kill_creativity/transcript

Photo credit: Girl with a bubble, Snapwire