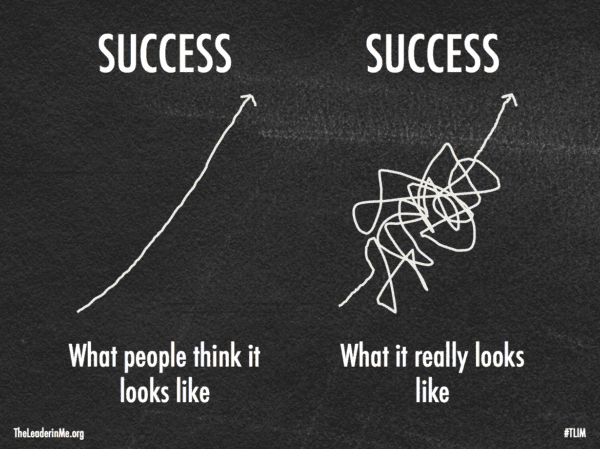

Way back when I was in second grade I had an amazing homeroom teacher, Mrs. Finley, who taught me how to knit using two wooden pencils and some yarn. I mastered the art of knitting and purling, but never dared to knit anything out of my scarf comfort zone. A few years ago, Youtube exploded with DIY tutorials. I decided to try knitting a hat using double pointed needles. Fast forward to the end result: I knit my first hat 5 or 6 times over. The sizing was off. The crown was too pointy. The hat wasn’t long enough. I purled a stitch instead of knitting it. I accidentally dropped a stitch. I learned so much from my mistakes. To this day, knitting isn’t scary for me because I learned how to problem solve my knitting failures. After hours of frustration, taking breaks, analyzing how to fix it, problem solving and starting over, I failed forward and became a much more confident knitter. Knitting became easier.

So, as educators, how do we make friends with failure? How should we address the concept of failure with students?

Failure is often perceived as an end result or something negative. Unfortunately, too many schools still focus on students getting the right answer and don’t allow for enough questioning, mistake-making and deep learning to happen. At LEARN, we subscribe to Dr. Dweck’s growth mindset theory where she describes failure as something that “can be a painful experience. But it doesn’t define you. It’s a problem to be faced, dealt with, and learned from” (Dweck, 2006). We can change our perception of failure to one of failing forward, problem solving, collecting data, or with younger students, by calling it a ‘beautiful oops’.

In Save Our Science: How to Inspire a New Generation of Scientists, Yale professor Ainissa Ramirez states, “Scientists fail all the time. We just brand it differently. We call it data.” Every experiment, whether successful or not, yields a wealth of data that builds our knowledge about the world and ourselves. She adds that “we need to teach children great stories of failure. Thomas Edison tried 10,000 different materials before he found the right one for the light bulb filament. Failure? No, that’s data. Lots of it. Or as he put it, he learned 9,999 ways that it didn’t work.” Indeed, failure is only failure when we fail to learn from it (Hogan, 2017).

Babies and toddlers are the perfect example of deep learning through risk-taking. They’ll fall so many times before being able to walk. They’ll climb if they see something merely climbable. They’ll learn to balance on something I wouldn’t have remotely imagined balancing on. They are natural risk-takers and discover the world that way. For many students, school and testing removes their sense of wonder, discovery and risk-taking when the focus is on grades.

It’s the Journey, Not the Destination

Allowing space for failures in the classroom is new to students, who may initially react with a sense of fear and hesitation. Addressing this in discussions can help to guide students to overcome their fears of not being good enough to succeed in a subject area while comparing themselves to higher-achieving students, or their fear of repeating past mistakes. Even though discussing failure can be painful for some students, these discussions provide us with teachable moments.

Fear, distress or frustration tolerance is an important life skill for students to master. As Dr. Amanda Mintzer, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute writes, “the ability to tolerate imperfection—that something is not going exactly your way—is oftentimes more important to learn than whatever the content subject is.” She suggests following a simple 3-step process when addressing failure:

1. Show empathy

2. Make yourself a model

3. Make it a teachable moment

It is also crucial to celebrate the process of how the students arrived at their solution(s) instead of what the solution is. A great way of doing so is by asking open-ended questions such as:

Tell me about… / Show me how… / What did you… / How did you… / Tell me what happened? / What can you do next time?

Full STEAM Ahead

Teachers are under a lot of pressure, as they must teach the curriculum in such a short period of time. How can we get students comfortable with the concept of failure in the limited time we have with them?

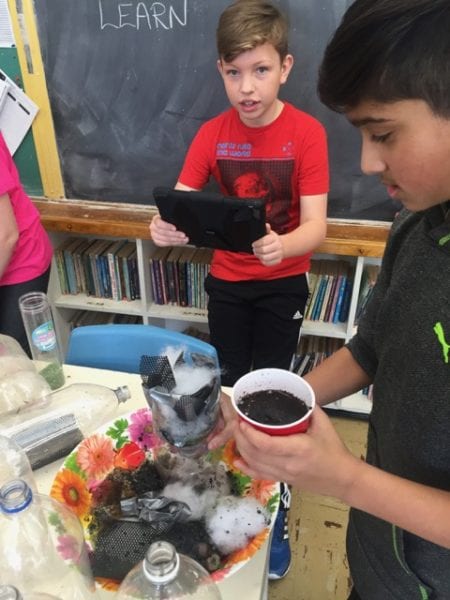

Students build a water filtration system at a LEARN pop-up makerspace

STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Math) education is a great way of building a positive relationship with failure. “In STEAM, failure is a fact of life” (Ramirez, 2013). STEAM activities promote a culture of experimentation. Students are provided with a safe space to explore different solutions, ask questions, take risks, test solutions, embrace failure and turn it into a learning opportunity. They learn persistence and resilience, design and innovation. Give them an opportunity, rather than have them follow a fixed set of detailed instructions with expected outcomes.

When introducing the concept of STEAM and Growth Mindset to students and teachers, we often refer to picture books. Picture books place learners in a specific mindset. Here are some examples of relatable reads that illustrate the concept of failing forward and problem solving:

1. The Most Magnificent Thing by Ashley Spires

2. Rosie Revere, Engineer by Andrea Beaty

3. The Dot by Peter H. Reynolds

For details on these titles and for more STEAM and Growth Mindset reading recommendations, view our LEARN’s Open Creative Space Library.

To learn more about STEAM and find examples of projects and activities, visit our Digital Competency in Action website.

Something to Reflect On

When it comes to failing forward, students need to feel safe and supported. Let your students know they can risk being wrong and they can ask questions that even you as a teacher may not know the answer. It won’t be an easy year teaching whether in class, online or both. As a teacher, I encourage you to model being a learner who isn’t afraid of failing when trying new things. Fail forward for and with your students.

I’m going to sign out with a few reflective questions:

How do you perceive failure? And your students? How can you create a safe and supported learning environment? As a teacher, do you model what it is to be a learner?

References

Arky, Beth (2019). How to Help Kids Learn to Fail

Dweck, Carol (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success

Hogan, Kathleen (2017). Failure is only failure if we fail to learn from it

Ramirez, Ainissa (2013). Save Our Science: How to Inspire a New Generation of Scientists

Image credit:

Success…What it really looks like: Leader in me: The Power of a Growth Mindset

LEARN’s pop-up makerspace: Chris Colley