The past two school years under pandemic restrictions have forced both students and teachers to face distance learning head on. It was a steep learning curve for most. Zoom, TEAMS, Meet, internet speeds, connectivity, document sharing… the list goes on. Congratulations to all for adapting and surviving these challenges.

The day-to-day use of technology in our schools is not a new concept. The most focused efforts over the past 30 years have been in the use of assistive technology for students with special needs. We may be at a point when we can address the integrated use of technology with all students. My question is: How can we look at the past two years’ experience and leverage the benefits to keep moving forward rather than “back” to normal in our teaching and learning practices?

To address this question, we must first look at how we got here.

The Laws

As far back as 1990, the USA had already passed the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) which has influenced much of the work since then. This is a civil rights law that protects individuals with disabilities against discrimination and establishes the right to reasonable accommodation (for comparison, the Accessible Canada Act only came into effect in 2019). Among other things, public content must be accessible, including websites .

In 1999, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) published the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0 (WCAG10). This set international standards for the web which were updated and revised in 2008 (WCAG2.0). The guidelines also provide recommendations for making web content accessible to a wide range of people with disabilities. The content that consultants, teachers, and students are producing can benefit from applying these guidelines thereby making learning more accessible for all. Provided at the end of this article is a table that summarizes some of these standards for teaching and learning purposes.

As early as 1978, Quebec was one of the first provinces to enact a law that promoted the inclusion of people with disabilities. This law was amended in 2004 to require ministries and government agencies to adhere to the WCAG 2.0 standards. An updated reference document was published in 2012: Version commentée du standard sur l’accessibilité d’un site web (SGQRI 008-01)

Education Policy

Unfortunately, the law only applies to the public sector and carries no penalties for non-compliance. However, it is a good reference point to work from and indicates that a conversation towards accessibility has been started within our province. Another conversation that was started around the turn of the century saw the introduction of a new Quebec Education Program. It introduced our educational system to the concept of competency-based learning.

“The focus on competencies entails establishing a different relationship to knowledge and refocusing on training students to think. The idea of a competency reflects the conviction that students should begin at school to develop the complex skills that will permit them to adapt to a changing environment later on. It implies the development of flexible intellectual tools that can be adjusted to changes and be used in the acquisition of new learnings,” (2001).

In the introduction of the QEP, reference is made to a 1994 report from the Conseil supérieur de l’éducation titled Preparing Our Youth for the 21st Century. The information explosion and rapid development of technologies were among many elements that needed to be addressed in a revised curriculum if it were to meet the needs of the students in the future. A future that is already here.

The use of new technologies called Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) was included in the different programs of study and was specifically presented as one of the nine Cross Curricular Competencies: “To use information and communications technologies,” (2000).

Funding to school boards to hire additional consultants to support the integrated use of technology in the classrooms was established in 2000 (RÉCIT). Budgets were also created to purchase ICT equipment for student use including internet backbones within school boards.

Over the past 20 years, billions of dollars have gone into both equipment and training in attempts to support and provide access to ICTs in our schools. However, bringing all of this into day-to-day teaching has been a slow struggle. There has never been enough access to technology for all students on a day-to-day basis to allow for the effective development of this competency. Having access to a computer lab once a week or a set of iPads or laptops in the classroom for a week or two for a project is not an “integrated use of technology.”

In 2018, the MEES introduced the Digital Action Plan with a $1.186 billion budget from 2018 to 2023 and 33 measures to accelerate the “shift to digital” in Quebec’s education system. Three areas were being addressed:

1) robotics (programming),

2) creative labs, and,

3) devices to support the other two.

In the past year, much of this funding has been put into devices in order to support the need for student access to online learning because of Covid-19.

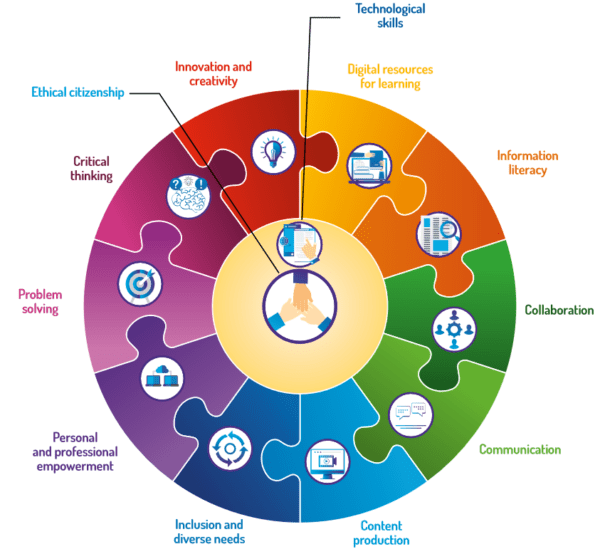

Measure 01 of the plan was to establish a reference framework of cross-curricular digital competencies at every level of education. This framework was published in the 2019 Digital Competency Framework. It describes the Digital Competency as one competency that has twelve dimensions. It is an expansion of the CCC from the QEP with an integration of many of the other CCC’s into the 12 dimensions.

Measure 01 of the plan was to establish a reference framework of cross-curricular digital competencies at every level of education. This framework was published in the 2019 Digital Competency Framework. It describes the Digital Competency as one competency that has twelve dimensions. It is an expansion of the CCC from the QEP with an integration of many of the other CCC’s into the 12 dimensions.

Bringing it all Together

2018 also saw the addition of personnel to the National RECIT network who were tasked with establishing as a pilot project, online courses for the secondary 4 & 5 matriculation subjects (FAD, Formation À Distance). The content for these FAD courses would be housed and supported by local servers within school boards.The Direction des ressources didactiques et pédagogique of the MEQ has created a working document for this team entitled: Application des normes d’accessibilité numériques pour la formation à distance (FAD), in which the W3C standards for web accessibility are drawn on to establish three levels of compliance that FAD courses should meet. At this point in time, they are expected to meet only the first level of compliance.

“Compliance with level 1 criteria makes it possible to meet the needs of students who have marked difficulties in reading and writing. DERs (Digital Educational Resources) that meet these criteria allow students to use assistive features such as text-to-speech and dynamic word tracking to access content,” (2018).

It is extremely encouraging to see accessibility being addressed in such a proactive fashion given how long we have been working to get the word out about the importance and benefits for all when universal access is considered and applied. Level 1 compliance with today’s technology should be inherent, not just for FAD course content but for all educational content that travels over our web network. That includes the documents and other learning artifacts that are created by consultants and teachers and shared with students through TEAMS and/or Google Classroom and the internet.

If these standards are used when content is being made, it will not really add extra time or effort and the products will be better designed and accessible to a wider range of students.

The table below outlines Level 1 compliance and can be applied to any Word processor, Powerpoint, Slide deck, PDF, web page, or other digital document.

As a consequence of Covid-19, students now have more access to educational computing tools. Multiple ways of exchanging information have been implemented and are being used on a regular basis in school and at home. Can we now leverage these benefits and tweak our digital pedagogical practices to ensure that content is accessible to as many of our students as possible?

Both access and accessibility will need training and support. What part will you play in your milieu?

Summary Table of Educational Accessibility Criteria

|

LEVEL 1 CRITERIA |

| Compliance with level 1 criteria makes it possible to meet the needs of students who have marked difficulties in reading and writing.

DERs that meet these criteria allow students to use assistive features such as text-to-speech and dynamic word tracking to access content. |

| 1.1 Ensure that textual content (eg: texts, tables) are usable and compatible with the reading and writing assistance functions

a) check that it is possible to select the text; |

| 1.2 Arrange the textual content in line with the visual content (eg: images, works of art) |

| To do this:

a) make sure images are not surrounded by text; |

Resources:

Assistive technology in the Classroom and at Home

LEARN’s Overview of the Digital Competency Framework

LEARN blog re: Digital Competency Framework

Using Accessibility Checker (Microsoft support)

Understanding and Applying the Digital Competency Framework by Craig Bullett

References:

Accessibility Guidelines 1.0. (1999). W3C Web Accessibility Initiative. https://www.w3.org/TR/WAI-WEBCONTENT/.

Accessibility Guidelines 2.0. (2008). W3C Web Accessibility Initiative. https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/.

Summary of the Accessible Canada Act. (2020). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/accessible-canada/act-summary.html.

Version commentée du standard sur l’accessibilité d’un site web (SGQRI 008-01). (2012). Gouvernement du Québec. https://www.tresor.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/PDF/ressources_informationnelles/AccessibiliteWeb/access_web_ve.pdf

Quebec Education Program (Elementary). (2001). Gouvernement du Québec. http://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/education/jeunes/pfeq/PFEQ_presentation-primaire_EN.pdf.

Digital Action Plan. (2018). Gouvernement du Québec. http://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/ministere/PAN_Plan_action_VA.pdf.

Digital Competency Framework. (2019). Gouvernement du Québec. http://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/ministere/Cadre-reference-competence-num-AN.pdf.