This post was co-written by Stacy Anne Allen and Paul Rombough

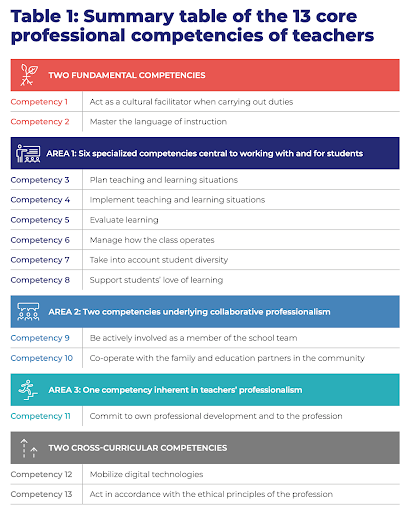

The new teacher competencies have appeared on the scene! If you are new to this comprehensive and compelling document, a Reference Framework for Professional Competencies for Teachers, here’s a bit of the context.

It is a series of “13 professional competencies that reaffirm and celebrate the beauty and complexity of the teaching profession” and essentially details many of the skills and values teachers develop throughout their careers. It also presents various challenges teachers may face, or should try to face, as we move forward into new educational realities that demand new ways of teaching and learning.

I found myself asking: How might this come into play for History and Geography teachers in Quebec?

I was drawn to the Culture Competency in particular, and as I read through the sections that describe it, I found myself questioning certain statements too, and inevitably relating them to our provincial curricula. I shared these questions with my RÉCIT colleague Stacy Anne Allen, who responded with great insight, and I have shared our exchange below.

Schools are the main ones to introduce cultural ideas/ways of understanding.

How might this apply to our schools in general?

Stacy:

By the time students enter school, they’ve already been introduced to cultural ways of understanding; culture is present in their family lives, communities, the media, etc.

Then, formal education introduces “school culture” which may support or contradict a student’s existing cultural identity. Schools should strive to foster cultural awareness to support healthy and positive identity formation.

Paul:

I agree, and for me, you hit both the personal and the political concerns I had when writing that question. So yes, the way my son’s school supports community-driven culture (or conversely its critique of consumer-driven cultural elements) plays a crucial role. How well teachers and schools are prepared to take on these roles – that is maybe the key question.

School is that culture manifested in competencies, skills, and knowledge.

How does this apply to the science of History?

Stacy:

Students, parents, and teachers should be prompted to think critically about how school is structured and what competencies, skills, and knowledge the education system is valuing. A critical analysis of a country’s education system is a great way to learn about the science of History. Students should become increasingly aware that the historical knowledge, skills, and competencies in curriculum documents are reflections of what is currently valued by the government and the dominant culture in a society. Alternative perspectives exist and teachers and students should be critical of what and how they’re learning, teaching and assessing. Being an effective cultural facilitator (Competency 1) requires teachers to reflect on the hidden curriculum that is present in their classrooms and allocate time towards learning about their students’ background, histories, wants, and desires (Competencies 7, 8 & 11). They can then plan to facilitate learning situations that respect and motivate the diverse needs of their students (Competencies 3, 4, 5 & 6).

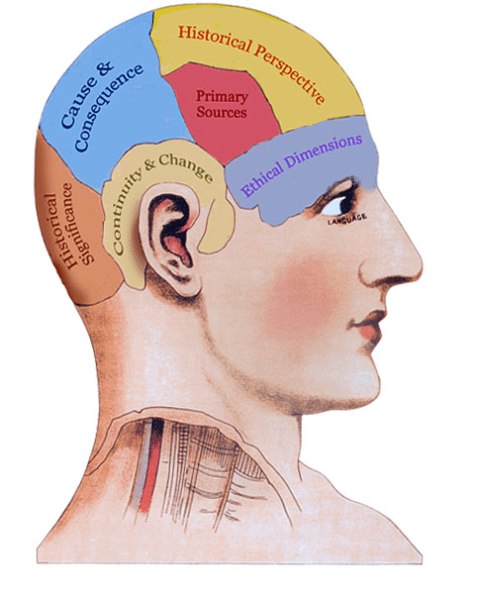

Image used with permission from Peter Seixas. Historical Thinking Concepts.

Paul:

Indeed, the country’s education system is fair game as a subject for critical analysis. But what I really like about your response is the notion of alternative perspectives and how various cultures can provide launching points for that critical analysis. The student’s cultural background and that of the local community are key, not only to help pin historical learning in local reality, but also, as you say, as being an expression of their wants, needs, and desires. I would only add that teachers could also make similar efforts to learn about other cultural perspectives, even when those alternative histories might not seem of local concern.

Black, Jewish, Indigenous, or even certain European historical experiences are not always an obvious or direct part of a community’s experience, but they are important to understand in order to trace a larger variety of experiences, ones that often seem only to exist outside the margins of our national historical narrative.

I also like what you said about “the science of history” but it led me to think in another direction. I thought of historical thinking skills and even our history program’s ‘Intellectual Operations’. Are those competencies and skills a manifestation of our culture? Can we assume they are valued in every culture?

In any case, as disciplinary tools and ways of thinking, concepts like “historical significance”, “historical perspective”, “the use of primary source evidence”, and the addition of an “ethical dimension” to the study of history, these manifestations of culture can also help us to think critically, and even to reflect upon that culture from which they emerged. They can help us to question which cultures we highlight and explore. Similarly, with regard to the skills we evaluate in our programs, like the identification and explanation of “cause and consequence” or of “continuity and change”, and even more basic skills like “situate on a map or timeline”, these skills can also be used to expose cultural hegemony and discover hidden cultures that are just as important to students and our communities.

School introduces cultural heritage, and that in itself is a selection [i.e. a choice].

How does this apply to the study of history programs and to chosen historical narratives?

Photo Credit: Stacy Anne Allen (CC BY 2.0)

Stacy:

When presenting students with historical narratives, teachers, as cultural facilitators, should plan learning situations where they explore alternative perspectives and/or multiple sources of historical information with their students. It is always good practice to compare and contrast narratives from two or more different groups to explore the same historic event. For example, a historical narrative on the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) may differ greatly depending on if it’s from the perspective of the Cree, the Inuit, or Hydro-Quebec.

Paul:

I agree wholeheartedly. We are always presenting a perspective via the slant taken on reporting an event, or the choice of examples, or in the way we delve deep into one angle while glossing over or completely missing another. I think a choice is always being made (in the history programs, in the textbooks and websites we trust, etc.) even when documented sources support those choices.

Who writes or who wrote? Who held the power of the pen? Who now holds the lens through which we find and then view the writings about the past? You mentioned the importance of perspective and in the case of the Cree, Inuit, and other Indigenous peoples, one should also consider and value how perspectives form. In many cases, their sources of information were oral, or experiential and based on daily life, and only more recently via their own writings and historical records. If our cultural heritage includes the story of the JBNQA, its territory, and the evolution of Hydro-Quebec, it should include the perspectives of all those involved.

It’s a constant problem. So many different cultural experiences are passed over as we research, then report on, and ultimately commemorate people and events. But as you say, we can only benefit from contrasting different groups’ experiences. It takes an effort though, on the part of both teachers and students. They have to first be critical of the prescribed and available versions of history, maybe even of their own community’s perspectives, then they have to also work hard to discover those perspectives that went missing.

The teacher then selects, and imbues meaning in the selections, so that students can in turn find their own meaning.

How might this apply to national, but also to provincial, local, group, personal, and family histories?

Stacy:

Again here, the information that the students are being presented with is filtered by the curriculum documents and the culture and pedagogical intentions of the educator. It is essential for teachers to ensure that students see themselves and their culture represented in history, and if not, are prompted to question why.

Photo credit: woodleywonderworks via Flickr. (CC BY 2.0)

Acting as a cultural facilitator means committing to continuous professional development and personal exploration. It requires educators to reflect on their implicit and explicit attitudes, biases, and ways of knowing. As an educator, I am constantly exploring how my personal biases and beliefs are connected to my pedagogical choices. I regularly discuss my pedagogical choices with my elementary students so that they’re developing an understanding of how perspective impacts the science of history. History is never neutral and as a cultural facilitator I feel ethically required to clearly articulate this to my students.

Paul:

I love the term you used, “cultural facilitator”. It highlights an essential aspect of the culture competency, where a main goal should be that students find their own meaning. Teachers must be careful as they select, and be conscious of when they themselves “imbue meaning in the selections”. I applaud your ability to reflect on your own biases. It’s not an easy thing to do “constantly” I think. But being transparent about your choices (as even being choices at all!) with your students is a great way to offer them the chance to get involved in the process. I am perhaps not as conscious of when choices I make result from my own biases, but I do love empowering students with many options and opportunities for choice, and with ways to make connections with their own personal and local experiences. There are so many routes to “finding meaning”, and so many tools to help them explore their own culture (or cultures!) and their own family’s past experiences navigating through those cultures.

Teachers enable students, through… artistic, literary, philosophical and scientific works, to help them find some resonance with their own questions.

How can course content work to provide answers to key questions and concerns? To personal questions? To student needs? Etc.

Stacy:

History can provide students with insight into their current context. For example, some students may not understand the reasons behind Indigenous Land Acknowledgements. History can provide valuable context and help them explore and answer these questions. In the past, I’ve had students raise questions about racism in their communities, images portrayed in the media, how and why their family life differs from students of other socio-economic backgrounds, ethnicities and cultures, etc. These questions are the starting point of true inquiry-based learning in the social sciences domain. I like the multidisciplinary nature of this quote; art, literature, philosophy, and science can also be used to explore historical events and their impacts.

Photo Credit: Paul Rombough (CC BY 2.0)

Paul:

Yes, and we need to carefully choose the art or literature we use in our classrooms to provide context and to find answers. Students get bombarded with media images that are not only inconsistent with their own experience but that don’t always provide any useful historical context. Cultural and scientific works (and ideas and processes) can indeed help them explore further, but the same yellow lights of caution need to shine. I see this all the time in text books with the pictures chosen to try to represent, for example, Indigenous groups. In the past, we have developed a few resources to help students more critically analyze media but the same carefulness needs to come from teachers when working with culturally charged material.

Do you have any other comments or anything else you would like to add?

Stacy:

While the Reference Framework for Professional Competencies for Teachers briefly mentions the TRC’s Calls of Action on page 14, this document should also be used in conjunction with the First Nations Education Council’s Competency 15: Value and promote Indigenous knowledge, worldviews, cultures and history (2020).

Indigenous and non-Indigenous educators may wonder how they can integrate Indigenous content and perspectives into Euro-centered curriculum documents and education systems. Some may also wonder where they can go for support, knowledge, and materials when they’re beginning to teach the Social Sciences, and other subjects, from an Indigenous perspective.

Reconciliation is everyone’s responsibility and I am looking forward to additional resources and training opportunities to support the 10 key elements put forth in the Competency 15 document by FNEC.

Paul:

Well, there is a great place to end this exchange, with the notion of “responsibility”. I agree that not only teachers but everyone needs to play an active role, that carrying forth a community’s culture, and revealing (and reconciling with) other cultures, often requires a sustained and conscious effort, and that the structures and resources coming out of the new Reference Framework and the FNEC 15th competency together are going to be essential tools for teachers moving forward.

Again, I hope this conversation doesn’t end here. Add your thoughts to any or all of these questions in the comments section of this post.

Featured Image: Canadian Mosaic Wall. Tim Van Horn via commons.wikimedia.org (CC BY-SA 4.0)