This post was written by Paul Rombough in collaboration with Sylwia Bielec, Ben Loomer & Stacy Anne Allen

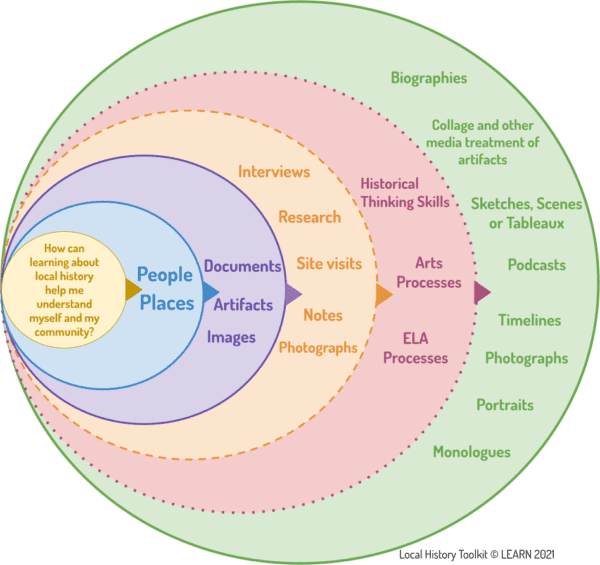

In the past couple of years we have been, for the most part, actively looking inward – first to our health and safety and then, by necessity, to reconciling with new routines. We are only recently beginning to look around us, first at our neighbours, then at the people in our communities, all of us struggling to find a way back into the ebb and flow of a larger world with its larger problems, challenges and opportunities. At the same time, we have been witness to what happens right here where we live during a global calamity, how we have been impacted, who the local heroes are, and the work that is being done on the ground. As a subject-area consultant, I have been working on making the History curriculum relevant in these contexts, and my colleagues have been reflecting on the French and English programs, on the Arts, on Outdoor Education, to name only a few of our starting points. Recently, we have come together as consultants from different fields to mount tools, strategies and project examples for teachers and students wishing to explore further the people and the history of the region where they live. A sort of learning in place. A fundamental question began our journey: How can learning about local history help me understand myself and my community?

Empathy is a good place to start a project – according to the design process – and also a good rule of thumb for life. It marks not just a place to begin but a way to discover who we are. Empathy also allows us to predict who is ready to learn more about our community’s present, past and distant past. Empathy is inclusive, because it considers as valuable everyone who lives or has lived in a place, which is to say: everyone who has been affected by changes over time in a particular place. We can start with the students we teach: Who are they? Who are their families? Then expand out from there. Who are the people who live around us, but also who are the people who moved in, and also who moved out?

Focusing on a historical period in history class can serve to narrow your field (See Timber reference in article here). Conversely, emphasizing an issue, such as immigration or land rights, helps to temporarily broaden the interval of the time you are studying (For example, when considering Origins and Migrations, consider who lives here now too). Once you choose a starting point, you might need to ask yourself more specific questions (See questions examples here). These types of strategies will help you establish what curriculum needs a local history project could fulfill, and vice versa.

One entry point to learning in place is to examine the people and places of your local community, both present and future, through a variety of traces. Sometimes those traces can be interviews with living people or site visits with accompanying photographs taken, and sometimes they can be documents, objects or artifacts from the past. We are in the process of creating different guides and tools that will allow students to explore and investigate people and places through a variety of means. Have you done similar things with your students? We hope you will share back your ideas, strategies and resources in the comments below!

People

Photo by David Ward, from “Experiences of Refugee Youth Image Gallery” a part of the Life Stories of Montrealers Project and the Project Spotlight | Mapping Memories: Stories of Refugee Youth In Montreal

Connecting and strengthening relations with people in your local community is an engaging and powerful way to further your understanding of past and present events and changes that have occurred over time. Interacting with others makes learning about the past more active and authentic. It also strengthens students’ communication and collaboration skills by promoting active citizenship.

As preparation for meeting with people, educators might wish to get students familiar with issues of cultural understanding, protocols to follow, and then maybe tools for project planning and interview guides. You might be able to talk with people you know, but in many cases the people who hold the knowledge are older, or hidden, their voices stifled by time and circumstance. In many cases, you might need to cross a river of misconception or misunderstandings to meet them. You might even have to be the one taught to listen first.

People also spring to life through the letters they wrote, the photographs taken of them, the portraits painted of them(or that they painted) and the decisions they made that shaped their lives and that of their communities. We will also be providing samples of tools that can help unpack documents, artifacts, and various other objects and situations while researching.

Places

As humans, each of us craves a sense of place. For some of us, it is to tie us more firmly to where we were born. For others, it is to grow roots into a new place where we have been transplanted. Connecting to places can have significant mental health benefits, as knowing our surroundings can help ground and center us. Additionally, connecting and building relationships to local places help us perceive continuity and changes and understand their importance – a direct tie-in to the history curriculum. Places can connect us to present and past events, people, and ourselves. Just observing and being present in certain places can make learning more authentic, cultivate one’s awareness of interconnectedness, and bring emotion and imaginativity into the curriculum. Finally, relationships to places can help develop an appreciation for our land and communities, promoting ecological awareness and feeling around protecting specific buildings, monuments, or sacred sites.

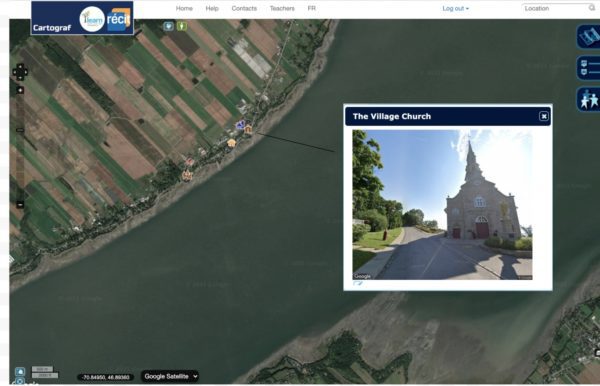

Researching, visiting, recording and documenting places involves research strategies, finding and contacting local partners, as well as ways of arranging class visits. It can also require strategies and tools for recording, photographing , ways to map or timeline or just note down findings. Where could you go? Which places can you learn about online? Once again, local contacts will be involved. Who could help point out key sites? In terms of physical structures long since gone, such as residences of prominent individuals, important government buildings, or even indigenous settlement locations and structures, what online sites and tools are available to try to find what once was a key location in your area?

Learn about People and Places

Source: Cartograf scenario The Seigneurial System

Documents, objects and other artifacts are sometimes all that remain of people and places. The mills of time are not always kind, and it may be that evidence of the people and places that made up the lived experience of an event have been lost, even as physical evidence was left behind. Museums are great places to examine objects and artefacts first hand, because usually museum guides there can help you make connections that are otherwise not obvious from the object alone. Public research sites like the BANQ or the National Archives also offer images, and some even provide 3D models of historically significant objects. In some cases, objects and documents have been transported elsewhere, outside of the community, but learning about them and discussing them with those around you will help shed light on their significance for the communities involved. But the greatest treasure trove of artifacts can come from the people themselves – photographs, ID cards, newspaper articles lovingly kept in envelopes, embroidered cloths, carved wooden spoons… the simple stuff of a life lived, revealed through meaningful connections with the people still alive to tell the important stories of a community. Students can examine the artifacts, listen to the stories passed down in families, and find ways of interpreting their historical significance.

Curriculum connections and the competencies we build

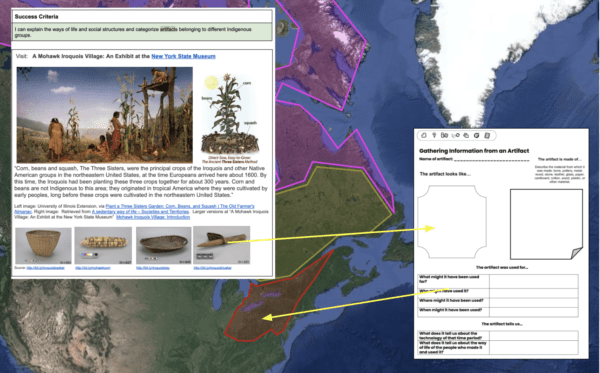

Artifacts used to help “explain the ways of life and social structures of different Indigenous groups” via Migrations, Indigenous Territories, Societies

The best projects are the ones that spark curiosity and engagement in students, allow them to build transferable skills, and also allow us to cover necessary curriculum. When engaging in a local history project, students use their real-world skills of planning and execution to find out about what happened, who was involved, and the specifics of how things change. They build and then demonstrate historical thinking skills, work with Arts and ELA processes and practice their French in the world outside the classroom. Additionally, when students use information, manage time and resources and communicate their findings effectively – they actively engage with the cross-curricular competencies. Not to mention that documenting, researching and communicating almost always involve digital competencies.

Projects Large or Small

Local history projects can be large or small, and be tailored to fit the time frame of your choosing. What exactly can you do in order to respond to your student’s curiosity about their community? What can you do in order to flesh out local truths based on the needs of those who are listening? The list we hope to build will hopefully inspire you to make a start. There are some great project ideas out there, that focus on a period of conflict, or document an experience of migration, or even that examine the experience of an original people, just to name a few. One of the intentions of this list is to show you some things that are possible, but also some things you may wish to avoid. And if it has made it to the stage of being broadcast at large, then likely it will show you how a project in your community can also be a reason to celebrate, an object of pride, or a means to reflect.

Where do you live? What do you know already about its history, and what would you like to find out? Who lives there, whose voices are loud or whose voices have fallen silent?

Got an idea for a local history project you have done or would like to do? Please let us know in the comments below, or via this form. And, if you want to take a peek at our Local History Kit section under development, drop on in!