Back in 2015, when history teacher Matt Russell (WQSB) piloted the new History of Quebec and Canada curriculum, he shared with us his insights on Planning for a new curriculum. On his LEARN blog post, Matt writes, “I began by unpacking the expectations of the two competencies – Characterizes a period in the history of Quebec and Canada, and Interprets a social phenomenon – and tried to develop a number of enduring understandings and essential questions that went along with them… My goal was to develop understandings and essential questions that could be universal, but also lead towards specific historical knowledge in our curriculum.” Essentially Matt prioritized higher learning goals, so-called essential questions, then he divided the entire curriculum up into more precise learning intentions, for which more precise sub-questions could be developed. Questions, Matt has often pointed out, can be “open and closed, overarching or topical” (Russell & Rombough, 2016). Here’s a variation on these different types of questions, in this case “open” vs. what is called “key”:

Open questions in history focus children’s attention, rouse curiosity and interest, drive and shape the investigation, elicit views and stimulate purposeful discussion. Open questions promote higher-order thinking and so help children to develop their thinking skills.

Key questions are overarching questions which give any lesson or topic unity and coherence, driving and focusing the investigation. A key question for a topic might be: Why do we learn about the Ancient Greeks? What was special about them? And for a lesson within the topic: Was there a Trojan War?

– Questions and Questioning

These structures – that is, essential, open and overarching questions combined with specific sub-questions, have been the backbone of the History resources we have been constructing at LEARN for the Secondary Cycle 2 History course for years. On our newly launched Secondary History site, has larger essential questions overarching through several sections, while the learning intentions contain more topical questions to help students focus in on the required knowledge for the course.

I have begun to rethink these questions and other uses for questions in general, not only as concerns their ability to direct learning, and their value as a practical tool, but also about their potential as a means for relevant student reflection.

Of Badges and Detectives

As alluded to above, questions can play a specific and practical role in our History and Geography courses. Students must know how to critically read and understand historical documents, but then our competency-based programs demand that students also focus more on how to use that knowledge. In our History classes that means characterizing a time period or interpreting social phenomena during those same times.

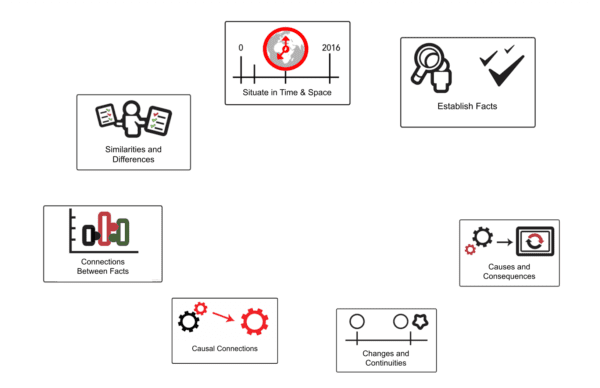

We call these specific processes the Intellectual Operations. Students establish facts (events, people, places), then they must also locate those same facts on maps, or place them chronologically on timelines. They must identify how things have changed (or not) as well as what key events cause what important and lasting consequences. Many guides and tools have been developed by LEARN and partners to describe and support these processes, and until recently I thought they were clear enough and sufficient.

We call these specific processes the Intellectual Operations. Students establish facts (events, people, places), then they must also locate those same facts on maps, or place them chronologically on timelines. They must identify how things have changed (or not) as well as what key events cause what important and lasting consequences. Many guides and tools have been developed by LEARN and partners to describe and support these processes, and until recently I thought they were clear enough and sufficient.

Recently however, I was showing some teachers the Elementary-level Intellectual Operations Badge Guides we had adapted for the English sector, and I stopped short and said out loud, “But wait, what is the question being asked? Where is the question actually written out?”

Even when I reworded the task from something that originally read, “Describe an economic activity in New France” to something with a key question word such as, “What was an economic activity in New France?”, it didn’t seem like I was asking the students anything key at all. More to the point, there was no opportunity to make a connection that was relevant, nor was there sufficient flexibility to allow for an answer to be made one’s own. What was needed were simpler types of questions and opportunities where students themselves get to say what they felt about the events, what they understood, and not just what we thought they should understand.

A resource series we developed recently made those older I.O. guides pale in comparison, precisely because this new approach also showcased a different way to formulate and use questions (plus, it was more fun!). The series is called Be a History Detective! and it asks students to identify and describe targeted characteristics of certain societies and their time periods. These tasks are prefaced by a variation of a simple personal goal such as, “Which one of these images best shows how the Iroquoian peoples adapted to their environment?”

A resource series we developed recently made those older I.O. guides pale in comparison, precisely because this new approach also showcased a different way to formulate and use questions (plus, it was more fun!). The series is called Be a History Detective! and it asks students to identify and describe targeted characteristics of certain societies and their time periods. These tasks are prefaced by a variation of a simple personal goal such as, “Which one of these images best shows how the Iroquoian peoples adapted to their environment?”

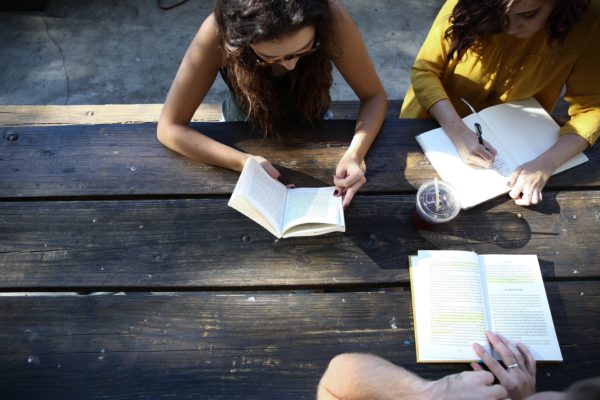

For many of these detective-style activities, there are several images that could work to solve the problem. Oftentimes, there are no wrong answers. Students are asked to demonstrate an idea or concept of their choosing in a way that they can explain for themselves. What is more, images are less threatening and more flexible for interpretation, and so, this kind of questioning works for many different kinds of learners.

Students can Write Questions too

Of course, I can hear some people saying, ‘What if learning to ask the right questions is in itself one of the learning goals?’ As Ronald Martinello writes, “one of the toughest skills a teacher can master is to effectively use questioning in the classroom. It really is a combination of skill and art. But if developing the skill to question is difficult for us, teaching that skill to students is even more challenging.” In a short post on Teaching Questioning Skills, Martinello, a history teacher himself, describes a process for getting students to brainstorm questions around a term or concept that they might know well, by offering up their own experiences and even any absurd ideas that come to mind. They eventually compile a list of questions they could use to help find answers to explain a topic. Then only after this organic and openly personal approach does he offer up a document (in this case an article) which students can use to find their answers to the questions.

I really liked this approach, not only because it reminded me of a design thinking process (that I explored when designing history-focused gaming ideas). This echoed my love for Wittgenstein’s emphasis on the use of language in what he termed a language-game (sprachspiel). “Wittgenstein argued that a word or even a sentence has meaning only as a result of the ‘rule’ of the ‘game’ being played. Depending on the context, for example, the utterance ‘Water!’ could be an order, the answer to a question, or some other form of communication.” That was the Wikipedia entry, which I used here with pleasure because it highlighted that part about “the game being played”. (Here’s a better source with more on his thoughts!)

I really liked this approach, not only because it reminded me of a design thinking process (that I explored when designing history-focused gaming ideas). This echoed my love for Wittgenstein’s emphasis on the use of language in what he termed a language-game (sprachspiel). “Wittgenstein argued that a word or even a sentence has meaning only as a result of the ‘rule’ of the ‘game’ being played. Depending on the context, for example, the utterance ‘Water!’ could be an order, the answer to a question, or some other form of communication.” That was the Wikipedia entry, which I used here with pleasure because it highlighted that part about “the game being played”. (Here’s a better source with more on his thoughts!)

Indeed, questioning skills for students are all part of the game they need to learn to play. We start off early in the year offering up key essential questions to be asked for different units, but the goal is for students to eventually learn to develop their own questions. If we are being honest, we also know they need to do it in such a way that they also cover the course material, learn the concepts prescribed on the exams, etc. It can be a fun, personal, and relevant game. But it’s still our game in some ways, isn’t it?

Questioning [and] the narrative itself

In a section of the new secondary student history site on Migrations-Territories-Societies, I worked through another approach based on a structured inquiry. In the Quebec & Canada program, the established narratives we follow insist on focusing on early migrations of peoples into North America as a point of historical origin. Okay, there are a lot of interesting things to know about those migrations. As one paragraph in the site’s curated resources points out, “many Indigenous cultures do not require the inclusion of this migration theory from the northwest to explain their existence in what is now Canada… they talk [instead] of their origins in oral histories, stories, and myths that link them intimately to the places they inhabit. The land, the stories commonly assert, was made for “the people,” and they were made to inhabit the land.” (2.3 The Aboriginal Americas). I wanted to ask, who is, who was, and who will be named (or not!) in the history books of the future?

For me, there were at least two threads of counter-narrative flowing through this topic. One has to do with Indigenous worldviews and experiences but the other has to do with the other has more to do with the specific way history plays out in a region or even a local community.

Consider the experience of the Iroquoians, who migrated from the far south to live in areas that were fertile, who are undoubtedly different from those of Cree and Inuit who had a more intimate relationship with northern climates and different northern routes. Every region, and even every local community, has its take on even that distant part of their history, i.e. how even the earliest migrations into their local territory occurred and panned out.

I included a Google slide document with the Sample Questions to ask about my own region. Through those slides I propose some specific questions (What is the land like there? What do I know about this area’s First Peoples? Were they nomadic? Etc.).

But then I thought it would be better for students to also come up with questions, so I looked back at those design thinking templates I had developed and came up with a large (i.e. placemat-sized) document called, Working with starter questions about … Who lives/lived here? It featured several helper categories and question types to help students get started with making their own questions that I hoped would apply specifically to their own community. This line of thinking (focused on local history) could work well in any time period or while studying any social phenomenon.

So that is the positive light in the sky, the ray of hope on the horizon that might lead students to a place they can call their own. Will it lead to answers, or just to more questions? I think you already know I am hoping for the latter. Counter-histories and local and cultural-focused opportunities abound, it’s a great thing that no two students will identify with these opportunities for exploring difference in the two same ways. To me that’s exactly how we can make things exciting and relevant in education.

So that is the positive light in the sky, the ray of hope on the horizon that might lead students to a place they can call their own. Will it lead to answers, or just to more questions? I think you already know I am hoping for the latter. Counter-histories and local and cultural-focused opportunities abound, it’s a great thing that no two students will identify with these opportunities for exploring difference in the two same ways. To me that’s exactly how we can make things exciting and relevant in education.

Language is a labyrinth of paths. You approach from one side and know your way about; you approach the same place from another side and no longer know your way about.

-Ludwig Wittgenstein

Doesn’t it seem like a better strategy to embrace that, and to offer and practise a variety of approaches, and even ones that do not expect exactly the same kinds of answers, nor the same kinds of questions!? Is the goal really to get through the labyrinth of language? Or is the goal to open as many entrances and exits as possible and let history be told by many voices?

References

Russell, M. & Rombough, P. (2016). Essential Questions to teaching using knowledge. Google Sheets Presentation.