Textbooks are one of the most common resources educators use to address Quebec’s Elementary Social Sciences Curriculum. This is no surprise since they’re always available, aligned with curriculum content, and contain straightforward teacher guides. Textbooks are not, however, synonymous with the curriculum. While they are good references, they should not be the only resource used. Students’ competencies are nurtured alongside their content knowledge when teachers expand on the material textbooks contain.

Publishing is a business; textbooks are designed to appeal to as many buyers as possible. Some contain more content than what can be covered in a typical school year which can overwhelm students and teachers. Others only provide quick overviews of topics that should be explored in-depth. Perhaps most concerning is that many textbooks are written from a Eurocentric or Western perspective and contain a limited number of voices. It is important to include multiple perspectives, particularly those of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Including the voices of local Indigenous Peoples in your practice is not only an important part of working towards reconciliation and the Calls to Action for Education, but it is also part of the professional competencies for educators in Quebec. Exclusively sticking to one book limits the diversity of perspectives students are exposed to in class.

While textbooks are an excellent resource, they should not be followed page by page. Alternative resources help connect the social sciences to today’s digital and physical world. Let’s incorporate a wider variety of resources to explore social phenomena with students. Providing students with multiple means of representation (i.e., different mediums like text, photos, and videos) will help meet their diverse needs and encourage inquisitive and empirical understanding. Also, it will simultaneously increase the number of marginalized voices. While many traditional resources for social sciences were text-based, our digital world makes it easier to access photos, videos, podcasts, and more. There are ample online resources for elementary social sciences, including LEARN’s Societies and Territories site.

While textbooks are an excellent resource, they should not be followed page by page. Alternative resources help connect the social sciences to today’s digital and physical world. Let’s incorporate a wider variety of resources to explore social phenomena with students. Providing students with multiple means of representation (i.e., different mediums like text, photos, and videos) will help meet their diverse needs and encourage inquisitive and empirical understanding. Also, it will simultaneously increase the number of marginalized voices. While many traditional resources for social sciences were text-based, our digital world makes it easier to access photos, videos, podcasts, and more. There are ample online resources for elementary social sciences, including LEARN’s Societies and Territories site.

Virtual Field Trips

One type of resource that has sprung up during the pandemic is virtual field trips or online tours. Many museums and historical sites now offer these free of charge. Students can use these visual virtual tours to establish facts and make connections between different periods and societies. It can be engaging to virtually ‘visit’ places that may have been too expensive or far away pre-pandemic. Here is a shortlist of Canadian Virtual Field Trips if you would like to explore using them.

While virtual field trips are good, one of the best ways to break from the textbook is to find local social sciences resources. I believe that the best educational resources are in one’s local community; people, places, and tangible artifacts bring the curriculum alive and promote active engagement. The LEARN Ped Team began exploring the relationship between local history, self-understanding, and belonging earlier this year (check our initial post here). I recently came across this beautiful series by Headspace on local history and ‘neighboring,’ which articulates the importance of local history and belonging. We are still adding to our local history toolkit, but I wanted to share two strategies that might help if you are beginning to ‘think local.’

Strategy #1

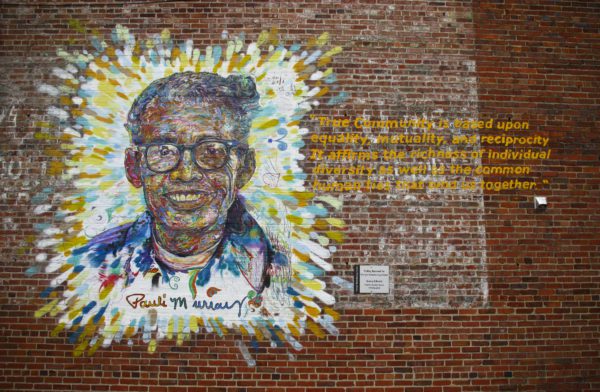

Community by Vanessa Marie Hernandez is licensed under CC BY-NC

The first strategy involves teaching about a broad period, society, or event from the curriculum and then exploring the same theme locally. Here is an example of how this strategy might play out for Quebec around 1905. A teacher could first present cycle 3 students with information about industries in Quebec in 1905. Afterward, students could research which industries were popular in their location in 1905 and 2021. By comparing what they learned provincially to what was going on in their town then and now, students would be nurturing competency 2 (‘To interpret change in a society and its territory’). They could also expand their knowledge and explore how local industries impacted local development, population, land use, etc.

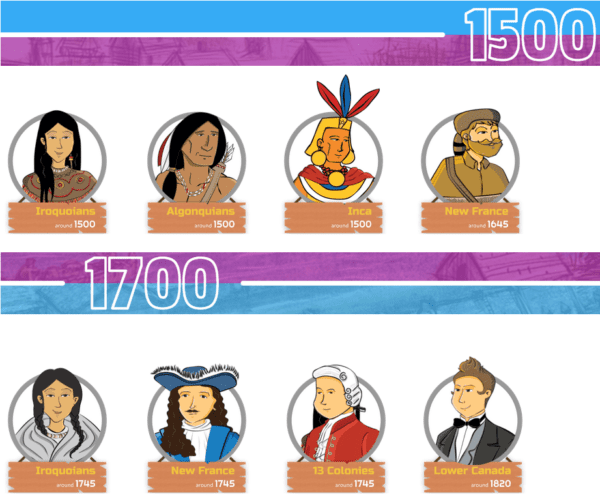

Unlike textbooks that are Eurocentric in design, the above approach supports Truth and Reconciliation because you can incorporate local Indigenous views and perspectives into your lesson plans. Students could learn about the Iroquois around 1500 using their textbooks. Then, they could research whether or not they live on land that was or is inhabited by Iroquois. Depending on the school’s location, students could then contact a local Iroquoian organization to learn more about how life for local Iroquois has changed over time. They may also learn more about the local community’s historical views and cultural practices. If possible, please build relationships with the local community to ensure the content is truthful and respectful.

Local history is an excellent opportunity to build mutually beneficial relationships and collaborate toward reconciliation. This strategy starts with curriculum outcomes and then turns locally to see how the broad themes are relevant to students’ communities. It is a good way to target competency 2 (‘To interpret change in a society and its territory’) and competency 3 (‘To be open to the diversity of societies and their territories’) as students can be prompted to examine how a society changes over time or how a different society or territory compares to their local community.

Ready for the second strategy?

You could explore your local community and then work outward toward broader curriculum themes. I am a particular fan of this strategy. As the weather warms up, it can be enjoyable to take long walks outside with your class. During these walks, you can take note of road signs, monuments, and gardens and use them to prompt social science inquiry. It can be a student-led inquiry where they are encouraged to ask questions about how their surroundings have changed over time. After an initial exploration, teachers can guide students toward the broader curriculum.

Community portraits by Sarah, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

While on a walk around my neighborhood, I discovered Ozias-Leduc street. When I got home, I did some research and discovered that the road was named after a Quebec painter who completed many religious works. If a student made this discovery, I might guide them toward curriculum topics like the role of the church and religious communities around 1905 or other eras. This approach is suitable for cycle 3 or above when students can do more independent research. The Community Profiles and Portraits Teacher’s Guide could be practical for people interested in using this strategy.

Local narratives or stories can also be expanded to broader curriculum themes. Inviting different individuals to tell stories to the class is a way to include alternative perspectives. Societies are collaborative so our approach to teaching about them should be too. Local narratives can be a powerful way to help students contextualize history and strengthen their relationships and feelings of belonging. They are also useful social science resources. Students can extrapolate their broader concepts and discover what was happening provincially, nationally, and internationally during a specific period.

Regardless of what resources you decided to pull from, students’ critical thinking, creativity, and digital competency should also be nurtured in social science class. Students and teachers should think critically about sources of information. It is important to consider whose voice is heard and whose is absent. I like to use a diversity wheel, like this one developed by Gardenswartz & Rowe, to help me. Tools like this can help teachers and students seek out alternative perspectives. Using websites created by museums or an organization affiliated with the particular territory or society that is being studied is a good strategy to ensure content is respectful and accurate.

Interactive Models

Social science classes don’t need to be limited to textbooks, pencils, and paper. Our society sure isn’t! Students can nurture their historical thinking skills and digital competency by creating documents that connect societies, territories, and time periods they are studying to one another. Scratch programming software by MIT is a fun and free way to break from routine. Here is a guide for students to create narratives about historical figures or prominent members of their local community.

Social science classes don’t need to be limited to textbooks, pencils, and paper. Our society sure isn’t! Students can nurture their historical thinking skills and digital competency by creating documents that connect societies, territories, and time periods they are studying to one another. Scratch programming software by MIT is a fun and free way to break from routine. Here is a guide for students to create narratives about historical figures or prominent members of their local community.

Before the end of the year, I challenge your students and you to branch out from the textbook to bridge the gap between today’s digital world and the past. Consider animating the curriculum by actively exploring and learning about your community and those in it; use a combination of textbook, online, and community resources. Listen and seek out the perspectives of local individuals on events and the past, build a true community of learners by building relationships, including different perspectives, and promoting active citizenship.