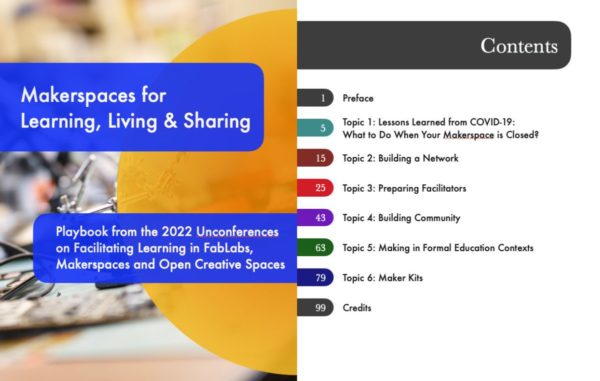

Last winter, 17 experts and leaders in the local maker movement and 80 maker practitioners from Quebec schools, CEGEPs, universities, community centers, libraries, and museums gathered online for The Unconference Events on Facilitating Learning in FabLabs, Makerspaces and Open Creative Spaces which led to the publication of a playbook titled: Makerspaces for Learning, Living and Sharing.

The unconference and the book are projects that began as a part of the graduate-level research with Concordia University’s Education Makers. Dr. Ann-Louise Davidson, a Professor of Education and Concordia University Research Chair in Maker Culture and Director of the Concordia University Innovation Lab, captained this effort with Université Laval professor Nadia Naffi and graduate students, to host these conversations and finalize the production of the playbook. Quebec educators who are recognized leaders in the maker movement were invited to lead some of the online discussions and co-author the playbook.

Recently, I spoke with Ann-Louise to discuss how her interests began with making and to gain some insight into the creation of a community of maker practitioners in Quebec.

What was your earliest memory of making?

When I was a kid, people who could make things were equivalent to God for me. I remember taking out my bicycle in the spring, and I had a flat tire. In my hometown it was hard to get to a bicycle repair shop, my family didn’t have the means for that anyway, so that meant I would have to wait for my father to fix it. But, I had an uncle who could fix anything and he said: ‘Oh, you know, let’s just take your wheel off and we’ll see where there’s an air leak.’

He put the bicycle tube in water and then I saw where the air was coming out and I was like ‘Wow!’ He took a pool repair kit and he took out an old tube of rubber cement glue and he patched it up. Then he put a brick on it and then I said ‘Okay, so how long?’… I remember staring at the cinder block waiting for the bicycle tube to get fixed. When we reassembled it I was in awe, it was like my uncle was a superhero. He fixed the tube! To me, anybody who had the capacity to fix [was godlike].

Why has making become so removed from human daily existence?

I’m looking at a lot of the problems people have nowadays. When they feel emptiness, it is very often because there’s nothing that’s a concrete project. Everything is digital. The relationships are on the screens, the kitchen is digital, and the car is more like operating an iPad so there’s no real contact with the rough external world.

Let’s bring this back to education, actually bring it back to that contact with objects where you’re learning is not just conceptual, the concepts you’re learning are things that actually exist. Maker education to me is really what brings back common sense in education.

Ann-Louise went on to describe how school and society need to work in collaboration rather than in isolation, as she further explains.

A very simple example…looking at your grandmother knitting a pair of socks gives you an understanding of where that object comes from and the effort that is necessary to make it. If a thread comes loose from it, rather than ignoring it you can bring it back to her and she can fix it.

When you buying objects that can just be replaced there’s no meaning to the object, the child has not participated in the fabrication or the conception or the creation of the object. So it’s a meaningless object, it’s just something you can buy. So everything becomes a little bit detached and there’s a definite alienation of the human being from its own natural environment.

Bringing maker education, maker culture inside schools is a way to get back some of that real stuff that you know human beings are…

Anybody who can have the capacity to think of how things work and then to reflect, to act, to exercise some agency whether it’s for creativity or for repair or for recycling or up-cycling or repurposing will find more relevance in what they are learning. I think that there’s a lot of value in this and it really defines us as human beings.

The introduction of maker culture into schools takes three elements according to Ann-Louise.

The Maker movement is a subculture of the DIY movement. For the movement to be alive, it needs spaces, makerspaces actually, and you need humans to be responsible for that space. It also needs on-ramps to bring novices into the spaces, allowing them to build, with experts giving them just enough assistance. The users and the culture actually have to define the mandate of the space and then you have to grow a community that is attached to that space.

If schools can bring in those three ingredients – school facilitators, novices to make, and community experts then the possibilities are endless because the community will grow with the space, and the space will grow with the community.

So what’s the bare minimal material wise that needs to be in the school to begin making?

This is very simple, you need some surfaces to work on, you need places to store projects and you need some tools and materials.

What defines tools and material is very simple, it’s anything that will allow you to create prototypes because in makerspaces we don’t do finished projects, you know it’s not products, that’s the difference between a makerspace and a factory.

Makerspaces are a place for creativity, collaboration, sharing, and iterating. So if you think that projects are not going to be completed in one period, you need a place to store projects and if you think about what tools are needed for prototyping well it could be as simple as cardboard and glue guns. [This act of prototyping allows students] to play with ideas, and externalize the concepts that you’re thinking about.

If you can have a variety of materials that’s great! You can have a bit of wood scraps, cardboard scraps, felt, some sewing material like a few needles and things like that… you can accumulate a collection of stuff to work with that doesn’t have to be expensive, it can all be stored in a few plastic containers and organized in a way that allows people to know what’s in those containers. That’s all you really need material-wise.

Then you need surfaces to work. Working on the floor is okay for kindergarten, but as you age and you want to do projects and if you want to have some safety you need to have tables or workbenches.

We need places where kids can be creative and learn the value of collaboration and learn to iterate so if something doesn’t work the first time you stick with it, you don’t give up, you can take risks, so spaces, where people are free to take risks, is what’s lacking in schools.

It’s like a catch-22 game, if everything is worth a mark then kids take no risks but when things are not worth marks kids don’t want to do it. So you have to find problems that will give them the motivation and enough curiosity and enough passion so that they will want to learn something, an activity or project in which they truly learn.

I’m not talking just about the kids who are good and motivated I’m talking about the kids who have lost their motivation to learn and very often I call that a learning depression. They don’t see the value in learning and why they should make an effort because they’ve had so many failures, so those are the kids that you have to target.

We are building a nation of innovators and we can’t deny the democratic aspects of giving everybody a chance to be an inventor. To dream of things, to be curious, to push their boundaries, to have a project and care for it, and struggle in order to solve problems and have pride, a story to tell around it, those are all things that can happen in a makerspace.

This led us to the playbook. Its intent is to help makers across Quebec get started with making in a variety of environments, from FabLabs, to museums. We focused on makerspaces in schools and facilitating these spaces was at the heart of the playbook.

Ann-Louise continues by telling the story of the original purpose of the project.

You know, Chris, I have four or five different drafts of maker books, and I always wanted to create a maker book that was a bit different than the others. They all seem to share the same kind of characteristics, like either how to create your makerspace or examples of maker projects, or a maker story, or how to make. I wanted something very distinct that would go back to the community. So the idea of the playbook was to create a book that could assist in creating a makerspace that people would really use in any kind of context, not just schools, but also libraries, community centres, or museums. And to me, any book like that, done by and for a community, it’s going to be much more relevant. So that was the idea of the playbook.

When we wanted to do the project originally, we had the great ambition to create a partnership between makerspaces and not just Montreal and Quebec, but also the other regions.

We wanted to create a network of maker facilitators that could share tips because very often people don’t know where to start. We wanted to share practices, projects, and stories. We also wanted to create unconference events that would happen physically. Then the pandemic hit. And by the time we got the money, we were not able to host the events. So we hosted the events online in the Winter of 2022. And that was the grand idea behind the unconference events. It was my ambition to write a collaborative playbook in which the answers came from the community of maker facilitators, not just from me.

Education Makers host the Winter 2022 unconference

It is a community that authored this playbook. I led the project and I used the resources I had, but the playbook is an indicator of what the ethos of making is, the sharing, the resourcefulness, the creativity, the collaboration. And I feel as though this playbook actually unified us, because now we know each other much more. So the concrete result of the playbook is the playbook itself, there’s a physical and a digital version, but the intangible is that so many people know each other now. And the next steps, I guess, would be to continue generating movement so that the community can continue moving together.

Community groups can actually bring a lot of meaning into people’s lives and help with mental health, help people bridge their anxiety of ‘What am I doing in my life?’, to “Oh, I have this community project. I have a purpose, a hobby, a project, a contribution.’

I’m not saying that it solves every problem, but having links to a community, having people that can help each other, rely on each other, share practices, share the good stuff, and connect at some events does a lot of good. It all ties back to this sense of being a human really, not only the making part, but that communal part, and that collaborative part. I mean it’s what makes us who we are. It can be that simple.

Ann-Louise came to an understanding of how making and community are entwined, “it changed me, because I was overseeing a lot of those conversations about makerspaces and I realized that the answer lies within the community, to get the answers to emerge, you need to find opportunities for the community to connect, that’s what you need.”

Makerspaces for Learning, Living and Sharing is a free digital resource, collectively created by maker communities across Quebec. It can be downloaded for free here: https://ecolebranchee.com/playbook-makerspaces/

Be sure to check out the Education Makers website which includes podcasts on the topics discussed at

The Unconference Events on Facilitating Learning in FabLabs, Makerspaces and Open Creative Spaces https://educationmakers.ca/project/unconference-on-facilitating-learning/

I want to send a huge shout-out to Ann-Louise Davidson for her leadership and for inspiring a community of makers. Thank you.

Photo credits:

Featured image: Teachers being makers at LEARN’s OCS Day

Bicycle wheel photo by Chepe Nicoli on Unsplash

Knit photo by Sophie Janotta from Pixabay

Workbench photo from the Makerspaces for Learning, Living and Sharing playbook

This interview was edited for clarity.