I was animating a short morning session on the practice of Action Research last week. It was Friday, to be exact, the kind of rainy morning you wished you were cocooned in a bathrobe somewhere or sipping a nice mug of tea.The attendees were all teachers participating in a formal research study conducted by Concordia University here in Montreal. I had long thought that one of the things that would round out this research in the eyes of practitioners was the voice of the participating teachers themselves. What was it like in the classroom when they introduced the new computer-based tools? What did they do about little Johnny who can’t sit still long enough to write his name, never mind do his Daily Five? And what about the noise? People love stories. Teachers love classroom stories.

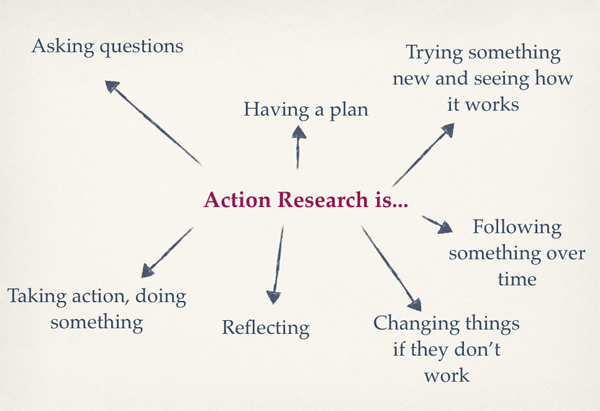

But is it enough to tell a good story? For a story to be compelling for educators, it has to answer a question or, perversely, to ask one. This is where qualitative approaches to educational research come in. I decided to go with Action Research because of its simplicity and straightforwardness. In fact, rather than providing my work-session teachers with a definition of the term action research, I asked them to brainstorm what it might be, based on the two words that comprise the term. I noted their responses on a slide in the Keynote presentation we were working from:

Intuitively, working with what they knew, the teachers were able to come up with the basic salient features of action research in about two minutes flat. Together, we found that

“Action Research is a fancy way of saying: let’s study what’s happening in our [classrooms] and decide how to make [them] a better place.” (Calhoun, 1994)

One of the main goals of Action Research is to lead to changes and improvements in teaching practices, and thus make schools (or online classrooms) better places to learn. More powerful than the most sophisticated workshop PD, action research is the cornerstone of reflective practice. Teachers who ask questions about their own practice and then decide on ways to take action are taking a mighty leap into self-driven learning (the kind we wish for all our students, no?). And if those same teachers follow up their planning with concrete action and the gathering of data about what they did, with reflection and sharing rounding off the cycle, they are engaging in the same kind of professional learning practiced by members of other professions, such as doctors. After all, why should they have all the fun 😉

The official Action Research cycle often looks something like this:

If you want to do some action research in your own practice, whether you are a classroom teacher, a consultant, a pre-service teacher or any other type of educator, you will probably want to begin by asking a question. A good question has the following attributes:

- It comes from your own practice

- It is in your sphere of influence (i.e. you can do something about it)

- It assumes that you are where you are

A question from your own practice

Often we are told what is important by others. Equally often, some issues become trendy and frequently discussed. But these might not be important to you at this time. So ask yourself: “What is important to me? What do I care about? What do I feel will make the most difference?” and choose a question that speaks to your teacher’s heart, no matter what the pundits tell you is important. Your school is different from other schools and your group of students is unique. You have the best insights as to where you need to put your energies and you will approach the issue with more zeal if it comes from you.

A question that is in your sphere of influence

Asking a question like: “I wonder if a shorter school day would be beneficial to my very active cohort of students” might be very interesting indeed, but might not be possible to explore. Your question needs to be something that you can answer by taking action. You could ask instead: “How can I use the very active nature of my students to help them learn math?”

A question that assumes that you are where you are

It’s no good asking a question whose scope is so far beyond you that just looking at it makes you break out into a cold sweat. A novice computer user should not, for instance, ask: “How can I integrate a variety of Web 2.0 tools into and across my curriculum?”. He or she might be better off with: “How can I set up and use a classroom blog?” which is more focused and manageable for a novice. (And speaking of classroom blogs, here is a great one from Mary Ellen Lynch’s Cycle 1 classroom).

The challenge

“Action research happens “in the swamp” where we live our day-to-day successes, frustrations, disappointments, and occasional miracles.” (Russell, 1997). I’ll be adding additional posts about action research between now and January. My challenge for you today is to ask a question from your practice and take the time this school year to engage in some action research of your own. Share your questions here! I would love to see them! We might discover some miracles along the way.

For more about Action Research:

Russell, Tom. (1997). Action Research: Who? Why? How? So What? An Introductory Guide for Teacher Candidates at Queen’s University. Found at http://resources.educ.queensu.ca/ar/guide.htm on October 7th, 2011

e-Lead: Leadership for Student Success – Action Research section. Found at http://www.e-lead.org/resources/resources.asp?ResourceID=9 on October 14th, 2011.

McNiff, J & Whitehead, J. (2005). Action Research for Teachers: A Practical Guide. London, David Fulton Publisher

Sylwia Bielec

LEARN

Interesting article. I liked the way you divided the types of questions to ask and suggested focussing what we need to ask yourselves. I have a question though, about the “cycle”, and I am wondering if the teachers you worked with had any ideas. While I think that Planning, Observing, Reflecting and Acting is what any good teacher does naturally, I have trouble with exactly how to Gather data or examples that would indicate something about my practice (i.e. the approach), that will tell me what is working. I mean, I can gather data about whether they are learning the subject matter, or improving their skills. But to know that it was because of the teaching strategy, or just because the content choice was just more interesting, or just because they just had more sleep that week… I am not sure. Did the teachers you worked with have any ideas as to “How to find out if “I” made a difference?”

Thanks for the feedback, Paul. Gathering data is one of the cornerstones of action research and probably its Achille’s heel as well! My answer to you has two parts:

1) I think that the kind of data you will gather depends on the question you ask, i.e. it is difficult to speculate as to what you might collect without a specific question from your practice.

2) One way to narrow down whether change stems specifically from what you did, is to do it more than once. You will quickly know what else is at play. And by having several instances of something to look at, you will be in a better position to judge.

Ah, the ultimate question… Is what I am doing making a real difference?

I was one of the teachers at the Action Research session on October 14th. I was really inspired by this approach.

I had proof of success by viewing the progress of my first grade students through ePEARL and by observing the ease at which they flew through the process of planning, doing and reflecting.

At the beginning of the year students struggled with the process of setting goals, giving feedback and reflecting. They needed a lot of scaffolding and often chose the same goals as the class stated on our class portfolio (I kept it on the Smart Board for students to refer to while working). At the end of the year students were deciding their own goals, they were giving feedback to each other about each others work, and they were independently reflecting on their work. I even had some students who used their portfolios through the summer to read stories. One also wrote when he did special activities over the vacation and he uploaded pictures to match.

This year I started out as the I.C.T. specialist and the classes were mixed. We had students who came from different schools. The students who were in my class last year rapidly jumped into their portfolios. They were able to set goals for an assignment right away without even seeming to think about it. The students that I had never taught, stared blankly. They had no idea what a goal was or how to go about deciding one. They were at the same point my students were at at the beginning of the previous year.

Now, I have a new group of grade ones and I am looking forward to observing their growth through ePEARL again.

It’s really incredible how quickly students can learn things like reflection and goal setting when you show them how to do it and help them with it at first through modelling and scaffolding. I hope that you are able to document (track) your students’ progress in goal setting. It would be really interesting to see samples of the same student over time and to know how (specifically what you did) you helped your students get from point A to point B.

Dear Sylwia,

Thanks for introducing “Action Research” to us last week. I was one of the teachers at that morning session. I am excited to be part of this group and very interested to learn more about “action research”. I am thinking of a few questions. 1. How can I best guide and support my students to develop self reflection in their learning. One plan I have is to verbalize my own self reflection more often after lessons – what worked /didn’t work. I could even ask them what worked and didn’t work. 2. My other question is management. I am implementing the Daily Five so that I can have stations in which I can integrate the computer laptops. I am full of hope that it will all work smoothly but am still worried. Will there be too much noise? Will I be able to work with small reading groups or will my attention always be distracted to help individuals. Wish I had more volunteer help. I do have some savy computer smart students that I will identify as experts. Are either of these questions good ones to identify? I’m not sure what to do next Sylwia. How would I track, assess or guage the impact of my actions. Thanks.

Mary Ellen

Hi Mary Ellen! Thank you for your comments. I’ll be writing about data collection next week so maybe there will be something helpful for you there. What I am getting from you is that one of your questions is something like: How do I integrate ABRA and ePEARL with the Daily Five early literacy structure? Then you have your subquestions or issues: How will I make sure that the noise level allows the students to concentrate on their tasks? How will I avoid becoming the computer bottleneck?

I think that if you do one thing at a time you will not become overwhelmed. Why not try to introduce the computer station outside of the Daily Five at first, at a time when other students do not need you to work with them. Then, as the students get more comfortable over the course of a few weeks, put it in as a ‘station’ or activity choice within the Daily Five structure. I think that the students need to be comfortable with the Daily Five on the one had and with ePEARL on the other hand before the two are merged, but I could be wrong!

Stay tuned for more about data collection!

Hi Mary Ellen,

You have raised some excellent questions and made great suggestions! Your strategies are great, and I am sure you will have some amazing results.

The next step is to implement, observe and make notes. Write a journal if you can, but sometimes it’s hard during the day to find time to write, so you can even keep some sticky notes next to each station, and write your different observations as you walk by. Use different colours for each group, and try to use time stamps, so that way you know how often you have to intervene.

Hope this helps!

Vanitha

Thank you for this great article Sylwia! Last year was my first year as a full time consultant. I found myself trying to help teachers as much as I could. But “did I really help?” I asked myself at the end of the year. Many teachers were pleased with my work but was it because I had helped them improve on their teaching practices or because I had done a little to much for them?

Am I really helping and how may I more effectively help teachers improve on their teaching practices? I think that this is one right question that I can explore to engage in some action research of my own.