“Because it’s 2015.” This Justin Trudeau quote went viral when asked why his new cabinet is half women. And yet, women in STEM careers (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics), have been on a steady decline since 1987 – with the lowest numbers being in the applied fields of engineering and computer science. While women have been underrepresented in scientific fields for decades, Forbes reports that “women have seen no employment growth in STEM jobs since 2000.” Meanwhile, Statistics Canada data shows that women accounted for only 39 percent of university graduates aged 25 to 34 with a STEM degree in 2011. How can we as educators encourage girls and young women to pursue careers in science and technology? What are some factors in our control when it comes to making STEM a more welcoming avenue of study? A scant few days after the 26th anniversary of the École Polytechnique massacre, these questions are more than pertinent.

The 2015 STEM Index, which measures the amount of people graduating in STEM programs, hasn’t really budged for decades with regards to women and certain minorities. In fact, “early biases, discrimination and social expectations still play a significant role, diverting students from the STEM pipeline.” The wind vane points to two compelling explanations of this phenomenon: the environment in which women grow up, in other words, home and school, both of which reflect long-held societal views on gender.

“Science, technology, engineering and mathematics become the tools with which to explore curiosity and to create change.” Haiyan Zhang, Innovation Director at Lift London, Microsoft Studios

Dr. Jenna Carpenter at a TEDx conference Engineering: where are the girls?

At Home

The American Association of University Women explains that girls begin feeling disconnected from STEM fields as early as grade one, and by the seventh grade, “many girls are ambivalent about these fields, and by the end of high school, fewer girls than boys plan to pursue STEM,” in higher education. What can parents do at home to open as many doors as possible for their daughters?

Limit media that promotes stereotypical images of women. Media and social support for gender bias against women in STEM activities must be cut off at the root. From games and toys to television and movies, our expectations and ill-informed nurturing of girls support, and even create, the imbalance of girls in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics.

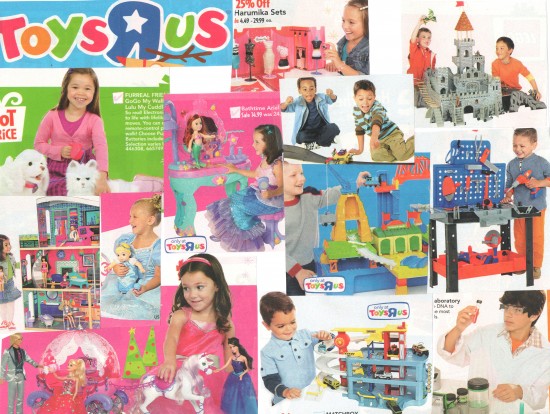

Become aware of your own unconscious biases. Studies show that parents, especially fathers, play a huge role in keeping girls out of STEM careers. Their biases are often unconscious. Harvard created an implicit bias test illustrating this fact, in hopes of preventing us from uprooting STEM potential and aspirations in our daughters. Families can begin to address these biases today by vetting the toys and games girls play. As the UK-based organization Let Toys be Toys states, “Stop limiting children’s interests by promoting some toys and books as being only for girls, and others as only for boys.” No more statements like, “Legos are for boys and Barbies are for girls.”

Retailer ToysRUs recently eliminated “Toys for Girls” and “Toys for Boys” sections in their stores – here’s hoping their advertising will follow suit. (Photo from the ToysRUs flyer)

“Extensive research shows that certain toys and games can help young children develop spatial logic and other analytical skills critical to science, technology, engineering and math… toys and games help to mold educational and career interests” says Andrea Guendelman, co-founder of Developer. This growth mindset can limit girls by putting Barbies in their hands instead of a power drills and chemistry sets.

Model STEM values. Ask questions about how things work. Take stuff apart. Go ahead, dads and moms, and get your daughter that robot she can program, or the science kit that makes elephant toothpaste. Build and create together. Encourage girls to play with power tools, and get their hands dirty. Code a website, build a circuit.

“If parents want to give their children a gift, the best thing they can do is to teach their children to love challenges, be intrigued by mistakes, enjoy effort, and keep on learning.” – Carol Dweck

Blog dedicated to women from science history @ http://sciencechicks.tumblr.com

And At School

Check your teacher bias. The Youth in Transition Survey by Statistics Canada shows that boys often have a better opinion of their abilities in STEM than do girls. “Fifty per cent of young men perceive their ability in math as “very good” or “excellent” compared with 37 per cent of young women, and those who perceived their mathematical skills more positively were more likely to choose a STEM program at university.” An alarming study out of Tel Aviv University released in 2015 found biases in the way elementary school teachers graded male and female students, suggesting that teachers have a role to play in the encouragement, or discouragement, they provide to girls in the early grades when it comes to math and science. The study gave teachers math tests taken by students known to them. Those same tests were also scored by teachers who did not know the identity or gender of the students. Consistently, across large numbers, teachers who knew the students’ gender graded the female students lower than the male students. And yet it’s 2015.

Include role models. There are no shortages of famous women in science for our young students to aspire to; programmer Ada Lovelace, French mathematician Émilie du Châtelet, American astronomer Vera Rubin, American software engineer Marissa Ann Mayer to name simply a few. Are we exposing our students to these female champions of STEM enough? After all, school is another crucial place to cultivate our girls’ STEM interests. It can be as simple as having a female guest speaker come into class and talk about how they became that engineer or that programmer; with the right exposure to female role models a significant change can happen in girls’ perception of what they think they can achieve.

Provide STEM activities that girls will find relevant. When looking at cognitive abilities in a school setting, research reveals in the area of spatial skills, boys consistently outperform girls. These spatial skills are needed in STEM fields such as engineering. However, this ability can stem from lack of practice in activities that develop these skills, which include hands-on manipulation and seeing STEM relevancy in their lives. Often positive STEM opportunities for girls happen outside of the classroom: at science museums, zoos, makerspaces, art hives and STEM clubs held during afterschool hours, weekends and summer breaks. These programs often give girls access to female mentors who help them believe they can and must participate.

“Girls want to make a difference, so give them hands-on, real-world problem-solving activities to show STEM is relevant and fun… Expose girls to the different areas of STEM and provide women mentors for girls and young women, so they, in turn, will mentor other girls.” Patty L. Fagin, PhD

Unspoken and unconscious misogyny is an effective silencer of women’s voices. Without the equal participation of women, we are only getting half of STEM’s potential to weed out the social and political problems that require scientific solutions.

I once was told “science is in everything” as it creates and maximizes tools to improve society as a whole: it grows best when fertilised by BOTH women and men sharing abilities, creativity, curiosity and hard work in the STEM field.

And, “Because it is 2015.”

************

Read more

Coe, Dr. Imogen. “How Gender Stereotyping Impacts Women in STEM.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 24 May 2015. Web. 1 Dec. 2015.

Gregory, J., Popolizio, R., & Carl, B. (2020, October 7). The empowering guide for women in tech in 2023. Website Planet. Retrieved January 19, 2023, from https://www.websiteplanet.com/blog/the-empowering-guide-for-women-in-tech/

Hango, Darcy. “Gender Differences in Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science (STEM) Programs at University.” Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. Government of Canada, 18 Dec. 2013. Web. 7 Dec. 2015.

“Why So Few? Women in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics.” PDF – Http://www.aauw.org/research/why-so-few/. AAUW, 1 Feb. 2010. Web. 1 Dec. 2015.

Huhman, Heather R. “STEM Fields And The Gender Gap: Where Are The Women?” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 20 June 2012. Web. 7 Dec. 2015.

Parke, Phoebe. “How to Get Girls into STEM — The Experts Speak – CNN.com.” CNN. Cable News Network, 14 Oct. 2014. Web. 1 Dec. 2015.

Taylor, Melissa. “5 Parenting Strategies to Develop a Growth Mindset | Imagination Soup.” Imagination Soup. Imagination Soup & Melissa Taylor, 17 Sept. 2014. Web. 7 Dec. 2015.

Tel Aviv University. “TAU study finds teacher prejudices put girls off math”. March 1, 2015. Web Dec 7, 2015.