This post was co-written by Julie Paré, Heather Scott, and Monic Farrell

How did you learn to read? What is literacy? How do we teach children how to read and write? What do we do when students struggle with reading and writing? What instructional practices have been disfavored and what should we be doing in the place of these?

It’s these types of questions that got Julie, Heather and myself thinking. We realized that we all had the same types of questions, but never had an opportunity to talk about them. We realized that if we had these questions, maybe others did too. So, why not create a space for literacy educators across Quebec to come together to explore the latest research on reading and writing? A space to talk about the questions they have, explore myths and misconceptions, receive and offer suggestions to problems, network, troubleshoot and connect. From these ideas, the LEARN and ALDI Literacy Networking Sessions were born.

What is Literacy?

The term literacy can mean different things to different people. So, to begin the professional development portion of the first Literacy Networking Session that took place on September 29th, we asked the participants to reflect on the term “literacy”.

Here is what they came up with:

Literacy has traditionally been thought of as reading and writing and although these are essential components of literacy, today our understanding of literacy encompasses much more.

Terms such as: meaning, communication and understanding were prominent in the participants’ ideas of literacy which aligns very nicely to the UNESCO definition:

Literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society (UNESCO, 2004; 2017, emphasis added).

We see that literacy serves as a gateway to great personal power for students as it enables them “…to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society” (UNESCO, 2004; 2017). However, there are many myths and misconceptions about literacy instruction which can have negative consequences on student literacy learning.

Jan Burkins and Kari Yates address many of these in their book Shifting the Balance by exploring practical solutions to incorporate the science of reading into the balanced literacy classroom. The book, which explores common misunderstandings in literacy instruction, inspired the structure of our first literacy networking session.

| Key Terms and Definitions Terms separated by a slash are interchangeable in our blog oral language / foundational language skills: includes speaking and listening abilities listening comprehension / language comprehension: the ability to derive meaning from spoken language word recognition / word reading: the ability to decode printed words |

Misconception #1

“Reading comprehension begins with print.”

-Burkins & Yates (2021)

This misconception assumes that a child’s ability to understand written texts only begins when they are able to read words on a page. Due to this misconception, many teachers wait until a child is able to decode before teaching them to comprehend texts.

In contrast to this misconception, Hogan, Adlof and Alonzo’s 2014 research study confirmed that the language comprehension skills required for reading comprehension begin to develop as soon as children learn to understand and use spoken language. This happens LONG before they start to decode words on a page.

From Shifting the Balance by Jan Burkins and Kari Yates, copyright © 2021, reproduced with permission of Stenhouse Publishers. www.stenhouse.com

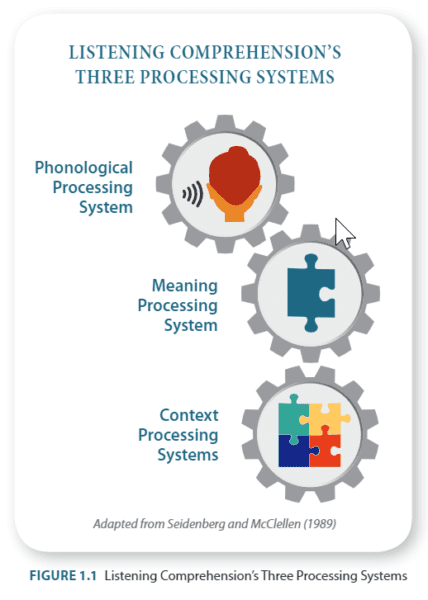

In their book Shifting the Balance, Burkins and Yates (2021) describe how language comprehension works, based on Seidenberg and McClelland’s Distributed, Developmental Model of Word Recognition and Naming (1989). They describe how three processing systems work together to produce listening comprehension.

How language comprehension works:

The 3 processing systems: Phonological, Meaning and Context

1. When working through the phonological processing system, a student will listen for speech sounds.

2. This links to the meaning processing system that does two things: it retrieves previously stored vocabulary and it organizes new words for later use.

3. Finally, the context processing system relies on the meaning processing system. This system uses the context, acquired background knowledge, and language structure to decide which meaning fits in the chosen context.

Let’s walk through this process with an example:

Click here to listen to a sample sentence.

Once you’ve heard this sentence, you have used your meaning processing system to retrieve definitions from your stored vocabulary. Your response could have been to think of scents such as smells, perfume, or scented candles.

After context is added (i‧e., ‘She collects vintage pennies and stores them in a photo album.’), you accessed information from your context processing system, returned to the meaning processing system, confirmed the new meaning with the context and finally, aligned your definition with a more meaningful interpretation of the word. This caused a rapid back and forth between the systems until you settled on the meaning of coins or pennies.

In the end, you were most likely successful in using your listening comprehension skills, notably your stored vocabulary and the context, to understand the recorded sentence.

The richness of a student’s vocabulary will determine the variety of meanings that they can access, allowing them to work flexibly as they add context, deepening their language comprehension (Burkins and Yates, 2021).

Imagine the impact on the student that has limited vocabulary. What if they only had one meaning for the word?

Since the listening comprehension abilities of young children predict later reading comprehension skills, as teachers, we must stretch the limits of our students’ language skills (Burkins and Yates, 2021). Opportunities to grow oral language – including vocabulary, background knowledge, sentence structure, and more – actually develop the comprehension mechanisms of reading (Quinn et al. 2015; Lervag, Hulme and Melby-Levag, 2017).

|

We need to support students by explicitly teaching oral language skills. |

How can we do this? Daily routines that include the following are a great way to start:

– Building background knowledge

– Interactive read alouds

– Storytelling

– Using complex vocabulary

– Dialogic reading & conversation

Reading aloud to students should continue throughout the grades. It has been identified as the most important activity for building the knowledge required to become a successful reader.

– Literacy Today

Misconception #2

“If children have strong oral language, they have most of what they need to learn to read.”

(Burkins & Yates, 2021).

This misconception assumes that as long as students have strong oral language skills, then they will effortlessly learn to read. Yes, as discussed above, oral language skills are extremely important, but even with strong oral language skills, if students don’t have adequate word reading skills, they will not be able to comprehend the spoken language represented in the print. As teachers, we need to support both word reading AND language comprehension.

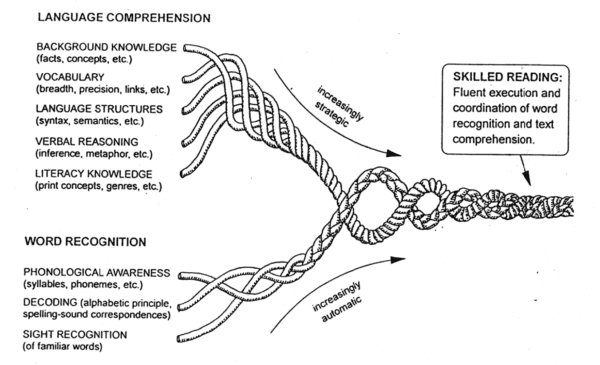

From Shifting the Balance by Jan Burkins and Kari Yates, copyright © 2021, reproduced with permission of Stenhouse Publishers. www.stenhouse.com

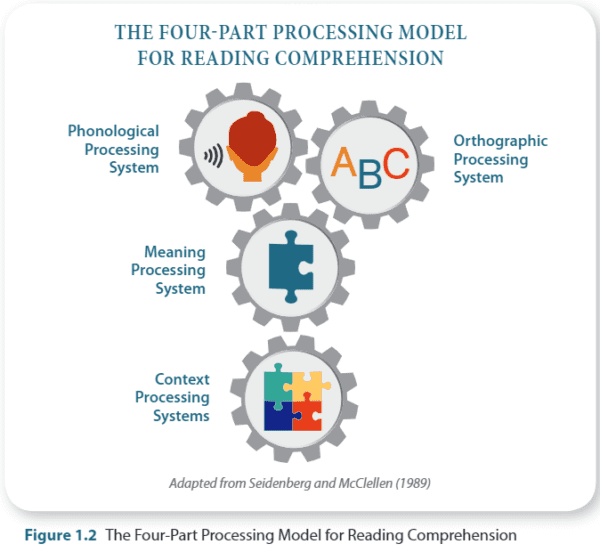

In this Four Part Processing Model for Reading Comprehension (1989), we see that the orthographic processing system has been included in Seidenberg and McClelland’s model as a crucial component of reading comprehension. To develop this system, children need to be taught how to make sense of print; they need to be explicitly taught to decode and to practice this to develop fluent word recognition.

Some models that highlight the importance of both word recognition and language comprehension skills include Gough & Tunmer’s ‘The Simple View of Reading’ (1986) and Scarborough’s ‘Reading Rope’ (2001).

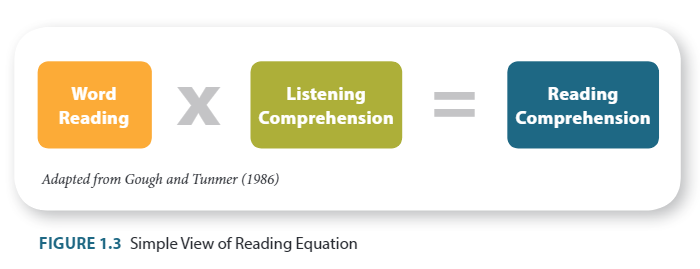

The Simple View of Reading (SVR) provides a framework for understanding the way word reading and listening comprehension both factor into the ultimate goal of reading comprehension.

From Shifting the Balance by Jan Burkins and Kari Yates, copyright © 2021, reproduced with permission of Stenhouse Publishers. www.stenhouse.com

As educators, we can think of students who have experienced difficulties with reading comprehension because either their listening comprehension or decoding was weak. Here are two examples:

– The student who reads a text fluently and accurately, but when asked what the text is about, is not able to articulate their comprehension of the text.

– The student for whom decoding is a great struggle and because they have to expend so much mental energy to decode the words, they do not form a clear understanding of the texts they read. If the same text were read to the child, they would understand it without hesitation, but because decoding gets in their way, their reading comprehension is lost.

The Simple View of Reading represents reading comprehension as the product of two separate but equally important skills. As we see in the examples above, if either of these skills is limited or missing altogether, the whole system—reading comprehension—breaks down.

See Reading Rocket’s Portraits of Struggling Readers for further examples.

The Reading Rope is a metaphor that elaborates on The Simple View’s two categories of essential reading skills: word recognition and language comprehension. The rope is further broken down, offering substrands of word recognition and language comprehension that make the rope strong (Scarborough, 2001).

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy. New York: Guilford Press.

This model can be very helpful to us literacy teachers because:

– It can help us to understand what skills might be breaking down for a child who is struggling with reading and;

– It can provide us with a guide for all the skills that need to be explicitly taught in order for us to nurture developing readers.

|

We need to support all components of students’ word recognition AND language comprehension. |

The first Literacy Networking Session focused on highlighting the distinct and important roles that both word recognition and language comprehension play in our students’ literacy development. In developing our ability to explicitly teach all the subskills in both of these areas, we take a very important step towards creating literacy success for all of our students. We can enable them “to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society (UNESCO, 2004; 2017).”

In our next session, we will dive deeper into the language comprehension strand when we focus on vocabulary instruction.

Register to join us via Zoom on November 24, from 4-5 PM

Refer to the Wakelet below for the resources from the Sept. 29, Literacy Networking Session and feel free to contact the session organizers, Heather Scott, Julie Paré and Monic Farrell, with questions.

References:

Burkins, J. & Yates, K. (2021). Shifting the Balance: 6 Ways to Bring the Science of Reading Into the Balanced Literacy Classroom. New Hampshire: Stenhouse Publishers. https://thesixshifts.com/

Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258600700104

Hogan, T. P., Adlof, S. M., & Alonzo, C. N. (2014). On the importance of listening comprehension. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(3), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2014.904441

Lervåg A, Hulme, C., & Melby-Lervåg M. (2018). Unpicking the developmental relationship between oral language skills and reading comprehension: it’s simple, but complex. Child Development, 89(5), 1821–1838. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12861

Quinn, J. M., Wagner, R. K., Petscher, Y., & Lopez, D. (2015). Developmental relations between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension: a latent change score modeling study. Child Development, 86(1), 159–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12292

Rayner, K., Foorman, B. R., Perfetti, C. A., Pesetsky, D., & Seidenberg, M. S. (2001). How psychological science informs the teaching of reading. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 2(2), 31–74.

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy. New York: Guilford Press.

Seidenberg, M. S., & McClelland, J. L. (1989). A distributed, developmental model of word recognition and naming. Psychological Review, 96(4), 523–568. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295X.96.4.523