Like most of you, I am aware of all the talk, the hype, the experiments, and even the long lists of how to actually use ChatGPT and other manifestations of AI in the classroom. But to be honest, for the most part, I have mostly been trying, with great effort, to avoid the endless Twitter feeds from my favourite educational gurus that offer solutions and ways to use these incredible tools. It is not because I doubt they could provide me with useful ideas or perspectives. It is, rather, because my first instinct is to imagine how I personally – as a teacher and not a consultant – would arrange my classes in such a way as to be sure I am evaluating real student work, knowledge acquisition, and most importantly competency development.

I know I am not alone. Many of you do not have the specific technical know-how to quickly take the risk of using AI in the classroom, much less to be able to monitor its use. Some of you don’t have up-to-date computers, good internet, or accounts set up in such a way for your students to safely and regularly access these services. And maybe the best reason of all: Most of you simply do not have the time to spare, to effectively adjust to using tech like this on a dime. Many of you are probably in panic mode, and one reason for writing this article was to put myself in your shoes.

“How can we know what students are doing for themselves?” Well, when I first heard this fear expressed I immediately imagined that the easiest solution was to get students to do everything right there in the classroom. That’s right, where you could watch them! Or, if you like, where you could restrict their access to certain online tools. But in my case, my gut feeling wasn’t wholly reactionary. What students are supposed to be developing anyway are the historical competencies (Sec. 3 & 4 example here), and they are supposed to be demonstrating those skills using what we call the appropriate “Intellectual Operations” (See Student Toolkit here). So, I figure if we can somehow get students to think and act historically, while we are all together and in the same room (and if we can find a way to then evaluate that thinking), then we might have avoided the problem of whether they used AI or not.

But there is another reason I wanted to initially write against this potential trend towards automation: for the last few years I have also been regularly struggling with how to get students actively involved in “doing History” rather than just recycling textbook information and practising for exams. Partly this is because when I was teaching I was not much of a disciplinarian. My solution to classroom management was always to keep students active. Individually or in groups, or even when the whole class was working silently, there was always a graphic organiser in hand, a quickly achievable goal in sight, and often even a timer clicking away. But another reason is that every day I see the potential of active history experiences as I research and design resources as a consultant for LEARN. And I believe that students could use these many available resources in more active ways.

Documents are key

Teachers often come to me with questions about how to help students succeed in our programs, and yes, to prepare for our provincial exams! One of the first things I say is to have students work regularly with a variety of different historical documents. History is not simply something that can be understood and explained in a linear fashion, from the first to the last chapter. History is scattered through myriad types of evidence that are available to historians at the time of studying it.

And much like the working historian, students can and should be actively developing their understanding of historical events and phenomena “for themselves” when they are dealing with the primary and secondary sources available to them. And ideally, in personal ways that no AI could ever do for them.

Teachers then need to develop tools to track how students essentially do what we call “Document Analysis”. Are students identifying things like the author, the style and time period of painting, etc.? Are they able to focus on key elements in the document, or use the document to support facts or conclusions? This is precisely what is required of our students when demonstrating all of our prescribed history competencies, whether involved in characterising a society or interpreting social phenomena over time.

Normally part of a larger learning process, like during a Learning & Evaluation Situation, or a Learning Unit or Project, working with documents can occur at various stages. So, LEARN provides specific tools for how to use documents that can be adjusted for various needs. They take the form of Intellectual Operation Guides and Worksheets (Secondary area | Elementary area), and they can help students to both choose documents correctly and to use the knowledge within them to answer complex questions.

I expect that AI tools will eventually allow students to just input all kinds of documents, for selection, to sift out what is appropriate, and even for interpretation (expanding on already-existing facial and object recognition features maybe). But for now, let’s concentrate on more tangible things, to help us think about how we could be doing this in our classrooms now!

First off, it can be a ton of work for a teacher alone to gather together these kinds of sources. Part of the work is already being done by myself and colleagues (LEARN) and by our various partners (School Boards, RECITUS, museums, etc.). But I say “part of the work” for a reason. Our web-based resources (see the new Secondary ¾ History site, or our English adaptation of the Societies and Territories site) should always be seen more as the tip of an iceberg, the edge of a larger historical process. Seemingly offering turnkey textbook-like solutions that provide content, documents and even strategies for using them, students still need to critically use these resources in class. First off, teachers and students should always engage in a process of rigorously checking even our sources. Then one should always follow all available links, to track and understand those sources but also to find even more related content. By doing this students find opportunities for profoundly individual understandings of facts, events, concepts and historical connections.

Image from Pixabay by Jarmoluk

The question is, can these kinds of opportunities be couched deep within a classroom experience now, so that they remain personal and unique to students, and to the moment, and thus divorced from the possibility of using an AI? I am still convinced they can.

With that question in mind, here are a few other sample trajectories you might take with your students, based on some of the current resources and strategies I am working on. They also reflect some of the experiences I am presently truly enjoying, as a researcher and curriculum designer. Some I have mentioned in other articles in different contexts (especially in Beginners No More: Social Sciences Online in a Digital Age), but some are new even to me, and are thus actively part of my own developing responses to the two primary concerns of this article (i.e. to AI or not, and active learning):

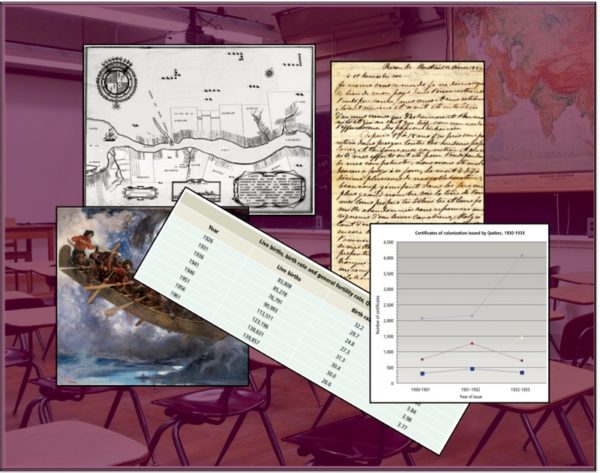

Image Analysis – In the moment

Considering and discussing the first impressions of an image can ignite and inform a learning experience. And a more complex and critical image analysis can also be a great way to learn more, and to show evidence of that learning. Thus, working with images individually, or during an in-class collaboration or discussion situation, students can acquire new knowledge and develop new opinions “in class” and “in that moment”, i.e. without referring to online aid. And again, whenever there is an opportunity for students to present and share their findings or connections to others, that is another way to avoid the urge to borrow unoriginal ideas from other sources.

There are several examples of this sort of strategy in our resources, and though originally designed for online work, the sizes and definitions of images that I always use ensure that they could also easily be printed out. Examples for Secondary-levels include asking students to Imagine War Experiences in WW1 and also where they Explore Immigrant Realities of French Canadians in 19th Century U.S. For Elementary, you can also see how our History Detective strategies offer a way for students to identify and explain (and personally identify with!) images that they must select amongst a larger group of images.

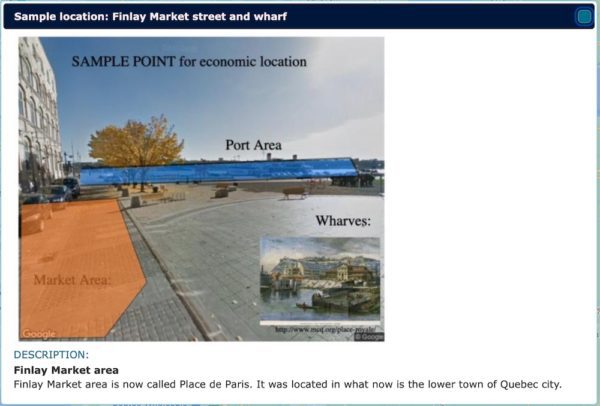

Another fantastic way to use images is to place and explain them on a Cartograf map! No two students will place images in the same way, at the same location. (E.g., Where would you place an image of a Roman coin on a map!) Make sure you have them explain why they chose that location. Another less well-known feature of Cartograf is its ability to edit images such that you can mark them up in order to interpret and explain them. This is demonstrated in the Quebec Heritage site scenario here and in the Geographic Sketch tutorial video that is available here.

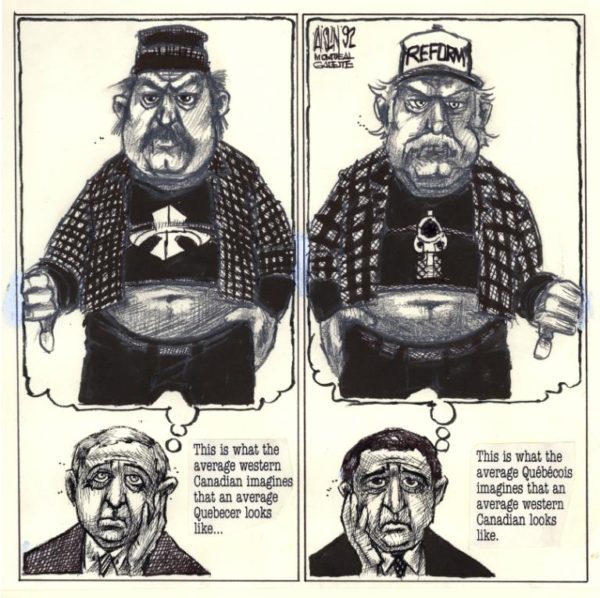

Cartoon and Caricature Analysis – Active Comparisons

Here I am not just thinking about cartoon imagery as a simple representation of an idea or event, but rather as a visual example of a historical document that demonstrates a viewpoint, on a controversial issue, for example, or a character in time.

East and Western Canadians, Aislin, 1992. musee-mccord-stewart.ca “In Copyright – Non-commercial Use Permitted”

As with images like paintings or photographs, students still need to examine editorial cartoons carefully first, as concerns the time period and other contexts. But what is great about these, and many historical documents really, is that since they take a position there are usually counter-position documents one can find and juxtapose. Added to these points of view, each student’s opinion can be also be included in the mix. And while students can actively characterise and interpret these kinds of documents, comparing them and judging them too, they can also be involved in finding and organising them in the first place. Any active and authentic research process is also a personalised one, and the results (i.e. the collections they come up with) can usually be verified as being their own and unique to them, especially when at some point the students must justify their choices and ideas in front of the class, for example, or in response to questions posed by other students. (I recently had a ball finding cartoons on the McCord site for our section on various Constitutional Crises in the 1980s)

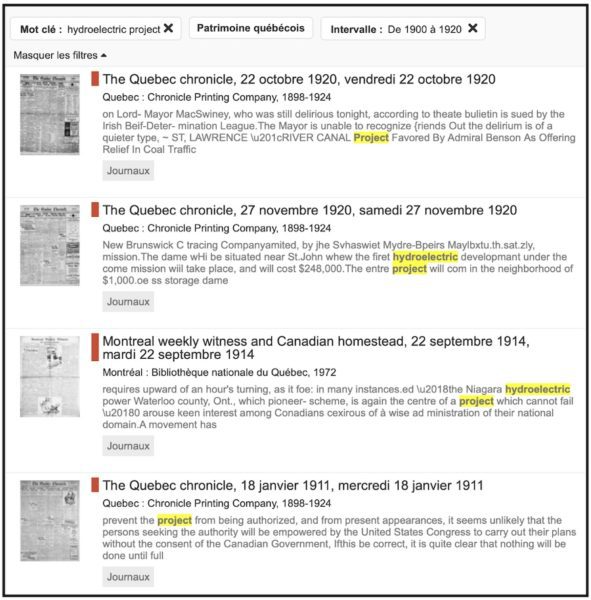

Newspaper Research – Revealing and Remarkable!

Recently I have also been having great fun sifting through old newspapers! Seriously, I can’t get enough of it, and what I am finding is both highly revealing about the society I am examining (i.e. Competency 1 – Characterization) and often covers truly “remarkable” events, which help to explain changes, and consequences, etc. (Competency 2 – Interpretation). Sites like BaNQ numerique are a real treat and fairly easy to use, since just searching for English words quickly narrows your search down to a few key newspapers available in Québec at the time.

Screenshot of BaNQ search for Hydroelectricity projects, then narrowing it down to dates from 1900-1920.

To help illustrate a process, when you search for information about early hydroelectric projects in Québec, you not only find images and articles about specific electricity projects at the time, but you can also browse the various other articles and ads that demonstrate how people lived and use that electricity, the political and international contexts for those developments, and many personal stories of the people living through those events and changes. Students doing this kind of research would discover very individual and potentially meaningful echoes of each time period. Again, providing them with the opportunity to then explain and interpret their findings (in the context of a guiding question or a specific task) would pretty much guarantee a sufficient degree of original thought, as well as provide evidence of knowledge acquisition and skill development, for a teacher to evaluate.

Games – Creation and Play

I don’t want to forget two key notions, and ways to potentially avoid some worries about unoriginal student work. One is the idea of creating something completely new, in groups, and in class. And the other is the idea that by playing a historical game students are actively demonstrating historical knowledge and abilities.

Feature image from my blog entry entitled How to Carry Forward Collaborative Online Practices

Games I and other educators have posted on LEARN help to review the course content and also practise specific historical skills. (Consider games like “Inca, Iroquoian and Algonquian: Connect the Facts Card Game” for example.) And when students are actually the ones who create these games, they get additional chances to understand and organise their learning, into concentrated, playable pieces. The targeted knowledge elements from their particular program could be, for example, represented on playing cards (here’s Explora!, another example card game.) Or, perhaps they could be hidden somewhere in a larger canvas as in our i-Spy game idea. Then, those elements could be incorporated into a gaming strategy where players must practise specific intellectual operations to help answer assigned questions or to characterise or compare societies in their times. In other words, get students to create and then play their and other students’ games. And even if some students resort to using an AI tool at certain points in the build process, they will still be acquiring, remembering and using knowledge in ways that are expected of them, and that are visible.

So, what will you do?

Throughout this article, I expect you have been rethinking many projects you, as an educator (or learner!), have experienced in your history class. You are already devising ways they can be more active, more physical, and more competency-based during actual class time.

Some of you are even struggling with making your evaluation practices more active as well, while maybe keeping them shorter and more contained and in the moment: i.e. maybe less like the traditional essay assignments sent home with students to complete on their own! Yes, organising for in-class experiences can be more work to set things up. But I remain convinced that the payback of having a well-managed and active classroom, not to mention not having to worry all the time about whether the intelligence is artificial or not, will be well worth it in the end.

Feature image credit:

Automatically generated at Cyberpunk Generator API | DeepAI, using the phrase: “Historical Documents using A.I.” 😉