Collaboration spéciale de Marla Williams, Coordonnatrice CPF – Québec

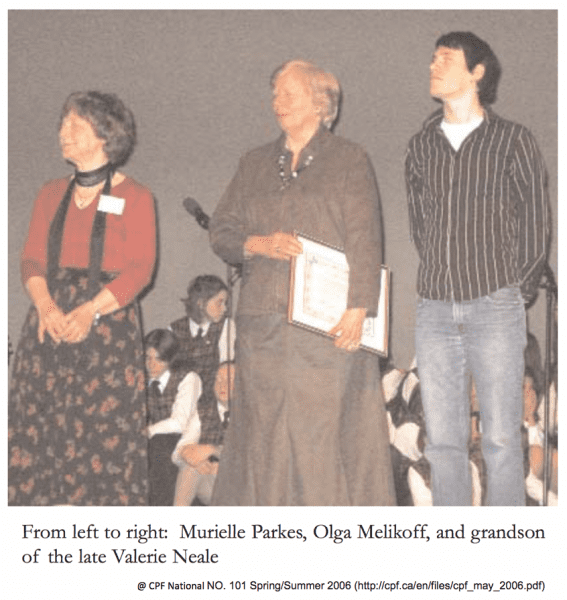

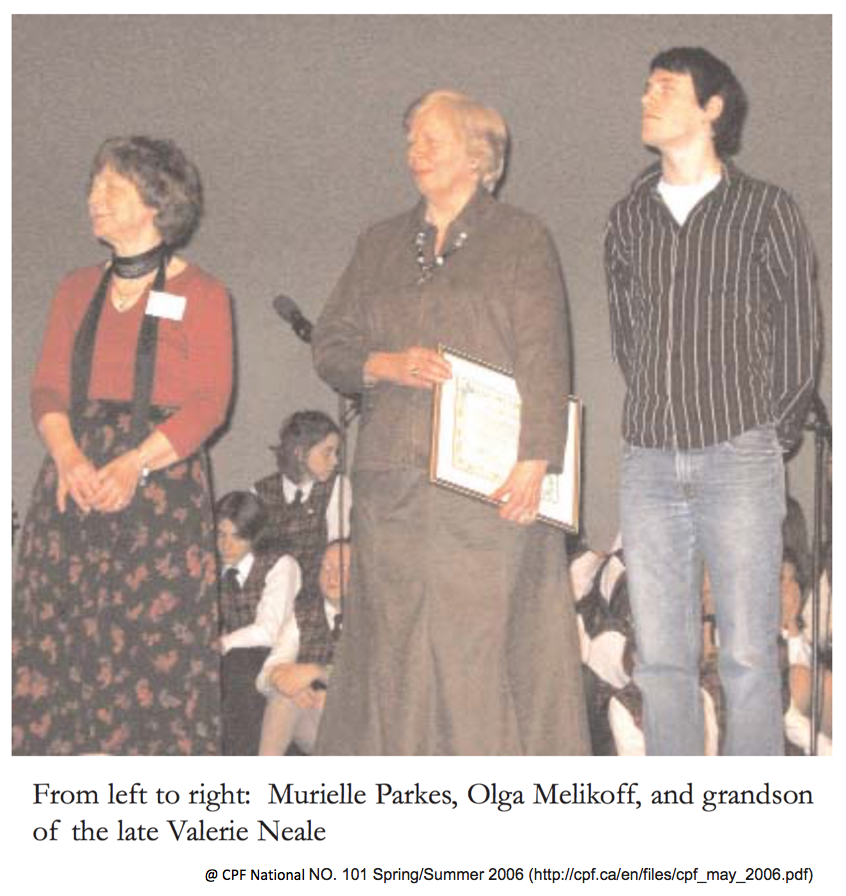

Murielle Parkes, Olga Melikoff, Valerie Neale.

Although these names are unfamiliar to most Canadian households, these three anglophone mothers from Montreal’s South Shore profoundly influenced Canada’s educational system through their perseverance and dedication to bringing about a now familiar program in which English-speaking children are fully instructed in the French language in the classroom: French Immersion.

Ces femmes incroyables, ces « mères fondatrices » de l’immersion française, méritent une attention toute particulière puisque l’année scolaire 2015-2016 marque un jalon important dans l’histoire du Canada : le 50e anniversaire de la création du premier programme d’immersion française au pays.

Retournons aux années 1960s…

Canada in the 1960s. Change was in the air. The Francophone population in Quebec was clamouring for greater protection of its culture and for a stronger voice in the political decision-making of the country. The landscape was also rapidly shifting in the province in favour of the primacy of the French language, where previously one had to learn English to succeed even though the majority spoke French. Issues surrounding languages and minority communities had taken the country by storm and as a result, the 1963 Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism was created to examine “the extent of bilingualism in the federal government, the role of public and private organizations in promoting better cultural relations, and the opportunities for Canadians to become bilingual in English and French” (The Canadian Encyclopedia).

C’est dans ce contexte que Mmes Parkes, Melikoff et Neale, se sont réunies avec une dizaine de parents de la Rive-Sud de Montréal afin de déterminer comment leurs enfants pourraient apprendre à maîtriser la langue française à l’intérieur du système scolaire. Ensemble, ces parents ont donc formé le St. Lambert Bilingual School Study Group. Désirant appuyer leurs idées sur des recherches solides, le groupe a contacté le professeur Wallace Lambert, un éminent psychologue et chercheur à l’Université McGill, ainsi que le docteur Wilder Penfield, un neurologue à l’Institut neurologique de Montréal, pour les aider à élaborer un plan d’action.

As Graham Fraser, Canada’s Commissioner of Official Languages, noted, “for a dozen parents in a South Shore suburb to seek out academic experts like Wallace Lambert and Wilder Penfield to figure out a way to make sure that their children would learn to speak French better than they could was an act of citizenship of the highest order. In its own way, it was a statement of their commitment to living in Quebec as a minority.” (Fraser, 11) They wanted their children to thrive in the province, and they embraced the transformations that were rapidly taking hold there.

Muni d’une détermination inébranlable, ce groupe de parents a essayé, tout au long de deux années éprouvantes, à convaincre le Chambly County Protestant School Board – dont le territoire aujourd’hui est sous le mandat de la commission scolaire Riverside– à accepter leur plan pour l’enseignement de la langue française dans la salle de classe. Enfin, en 1965, suite à une longue bataille ardue, ils ont reçu le feu vert pour mettre en œuvre l’immersion française dans une classe de maternelle à la Margaret Pendlebury Elementary School, école située à Saint-Lambert. Le jour de l’inscription, les portes se sont ouvertes à 13h et en seulement cinq minutes, 26 élèves, soit le maximum d’inscriptions possibles, ont été inscrits par leurs parents. Les autres parents intéressés par le programme ont dû être refusés.

Their efforts bore fruit. The teachers and parents involved in this novel pilot project were satisfied with how things were progressing and the young learners were feeling confident in their ability to speak their second language. Still facing resistance from the School Board, however, the mothers asked McGill researchers to study the effect the program was having on the young learners. In 1969, the results were published and they were promising: the program was working.

Ces résultats positifs, soutenus par la recherche, ont motivé des centaines d’autres parents à travers le pays, qui exigeaient également un changement, à établir des programmes similaires ailleurs au Canada. En tant que tels, des programmes éparpillés d’immersion française ont commencé à surgir à Ottawa, Toronto, Coquitlam et Sackville pendant les années 60s et 70s. Voulant étendre ces programmes encore plus loin, des parents ont rencontré le commissaire aux langues officielles, Keith Spicer, à Ottawa en 1977. De cette rencontre est né le projet Canadian Parents for French (CPF), un groupe qui revendique depuis plus de 38 ans pour plus de programmes de français langue seconde dans le système scolaire à l’échelle nationale. Leurs efforts concertés ont permis de nombreuses réussites et une montée en flèche des statistiques sur l’immersion française au Canada. Effectivement, les inscriptions en immersion française ont augmenté d’environ 650% dans les décennies qui ont suivi la création du CPF et aujourd’hui, plus de 300,000 étudiants sont inscrits dans ces programmes à travers le Canada.

French Immersion, also known as the “great Canadian experiment that worked”. A program that has been emulated worldwide, in countries as far away as Japan and New Zealand. Although French Immersion still has its many critics and flaws, such as enrolment caps and a lack of support for students with learning disabilities, committed parents from around the country are working hard to ameliorate access to French second language programs and to respond to all its students’ needs.

Grâce à leur détermination, Murielle Parkes, Olga Melikoff, and Valerie Neale ont donné le courage et la conviction aux milliers de parents qui se mobilisent encore aujourd’hui pour l’amélioration du programme. Tant qu’ils continueront à se battre, et nous savons qu’ils le feront, nous pouvons être assurés que de plus en plus d’élèves apprendront et prospéreront dans leur deuxième langue officielle.

On a final note, the Riverside School Board – now a firm supporter of French Immersion – gave the women a plaque on the 40th Anniversary of French Immersion, exactly 10 years ago. On it was engraved an inspiring quote from the anthropologist Margaret Meade: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

Sources:

CPF National News. “40th Anniversary of first French immersion model in Canada celebrated.” ISSN 1202-7384 NO. 101 Spring/Summer 2006. Online reference: http://cpf.ca/en/files/cpf_may_2006.pdf

Fraser, Graham. “Immersion Schools: Wallace Lambert’s Legacy,” In CPF Magazine Fall/Winter 2015: 9-14. Online reference: http://cpf.ca/en/files/CPFMagazine_Fall2015_Vol3Issue1_v8_E-VERSION.pdf

“French Immersion Changed Canada.” The Gazette. March 20, 2006. Online Reference: http://www.canada.com/story.html?id=ace0d2e8-4cc1-44b7-b73b-4b3f53dd6c5b

Government of Alberta. Department of Education. “How did French immersion start?” Online reference: https://education.alberta.ca/parents/resources/youcanhelp/solution/start/

Laing, G. “Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada, 2015. Online reference: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/royal-commission-on-bilingualism-and-biculturalism/

I was in the first (or one of the first) cohorts of French immersion in the old Lakeshore School Board in the early 70’s. I remember that I wasn’t happy about being placed in a french immersion program at the time. I was entering Grade 4 and probably about 1/2 of my peers remained in the regular English language program.

When I reached high school I realized what a valuable gift I had been given – the ability to speak a second language and converse with my neighbours in their own language.

My only regret is that I didn’t enter French immersion earlier. My daughter is in an intensive French immersion program (85-90% until Grade 4) and I can already see that her mastery of the language will soon exceed my own skills.

That is so true – a second (or third, or fourth) language is truly a gift.