This post was a collaboration between Craig Bullett, Michael Clarke & Emma Legault

We have passed through a portal into another world, one forever changed by the pandemic, as Homa Tavangar and Will Richardson observe in their book: 9 BIG Questions Schools Must Answer to Avoid Going “Back to Normal”. A shifted reality casts current educational practices in a new light and so, it is easier to question what is taken for granted and what we consider to be ‘normal’. The BIG Questions Institute that they run is invested in helping educators across the world navigate an increasingly unpredictable future by posing incisive questions and facilitating conversations about what learning looks like, or could look like, in a world reshaped by systemic issues.

There is a Crack in Everything, That’s How the Light Gets in.

– Leonard Cohen

Recently, a research project was submitted to the Ministry titled: What Does the English-speaking Educational Community in Québec Envisage Beyond the Pandemic? The research question emerged during previous LCEEQ meetings to look into common elements affecting various constituent groups (i.e. school board, teachers, administrators, union representatives, etc.) in the English sector. The two-year project is being led by Dr. Alain Breuleux of McGill University. He is supported by an advisory group composed of members of the Universities at the LCEEQ Table (Bishop’s, Concordia, and McGill).

The LEARN team had the opportunity to openly discuss the BIG questions (featured below) with Will and Homa as part of this research project. We have recorded the interesting nuggets from our discussion in this post but you may find it impactful or useful to ask (and re-ask) the questions in your own context:

- What is Sacred?

- What is Learning?

- Where is the Power?

- Why do we ______?

- Who is Unheard?

- Are we Literate?

- Are we OK?

- Are we Connected?

- What’s Next?

By the end of our group discussion, we found that some issues are simply beyond the capacity of any singular individual to address. In fact, many of the problems we face, such as climate change, racial inequity in the justice system, COVID-19, or gender pay inequity, can only be answered by a sustained community response at the local, provincial, and national levels.

Our struggles and successes in addressing systemic inequities also helps to clarify our vision. Although we have inherited flawed systems, we can still reject the ‘myth of the average’, design to the edges, and include every learner on a path to a more sustainable future. We hope that this post sparks similar conversations within your communities as we all find our footing in this new reality.

We have to remember that what we observe is not nature in itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.

– Werner Heisenberg

Preface: Not all questions are created equal

How does a teacher educate students so that they are knowledgeable and skillful in industries that have not yet been invented? What type of questions can we imagine these students asking in the future? Does it matter how those questions are posed and to whom? Like a candy necklace, questions can string us along towards interesting discussions but they may also result in circular reasoning as we wonder aloud but decide upon nothing. Not all questions are created equal.

How does a teacher educate students so that they are knowledgeable and skillful in industries that have not yet been invented? What type of questions can we imagine these students asking in the future? Does it matter how those questions are posed and to whom? Like a candy necklace, questions can string us along towards interesting discussions but they may also result in circular reasoning as we wonder aloud but decide upon nothing. Not all questions are created equal.

No one may be able to predict the future but within our learning communities lies a deep expertise and a shared understanding of the institutions that we seek to change from within. Like the parable of blind men collectively describing an elephant, we will end up lost and confused if we do not work together. Our institutions will not save us. We must save our institutions.

BIG Q: What is Sacred?

What is considered sacred in education will vary depending on who you ask. This is a crucial reminder of the importance to include the perspectives of all stakeholders. For instance, some items which emerged as sacred in our conversations included the social aspect of learning such as friendships and relationship-building. The reciprocity of learning was identified as integral to building trust, whether it’s between a student and a teacher, or among students or teachers themselves. It takes a village to raise a child.

One particular question struck a chord during our brainstorming session: What might our most vulnerable students consider sacred? Have we considered safety in all its forms? Physical, emotional, and psychological safety are increasingly subjects of interest. However, there is no quick and fast solution for these challenges. It is vital to support students in the authentic expression of their needs and to ensure that they have access to trusted adults (i.e. parents, school teams, and/or social service providers) who can meaningfully address their concerns. Every time a need is understood and met, trust is built. Reliable understanding will become vital in an increasingly uncertain and chaotic world.

Recent research shows that Quebec students are increasingly reporting symptoms of generalized anxiety as well as “higher levels of test anxiety, fear of judgment and perfectionism” than before the pandemic (Lane et al., 2021). A new normal may be emerging that could prove detrimental to the long-term educational goals of many learners today. Is this a new normal we are willing to accept?

BIG Q: What is Learning?

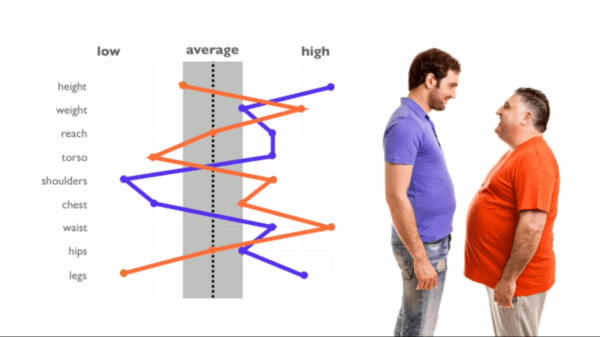

Our conversation about this BIG question was heavily influenced by a TEDxSonomaCounty talk delivered by Todd Rose. He challenged the “myth of average”, arguing that the desire to average out individual differences within a system or institution by catering to the lowest common denominator merely results in a mismatch between the needs of the stakeholders and the constraints imposed on them by the system. In other words, by focusing on what is ‘normal’, or ‘common’, or easiest to accommodate for, we neglect the wide diversity that naturally emerges when lots of people are grouped together.

Todd spoke about the history of how engineers had to design new pilot seats for jet planes. He described how they had learned that if the seats were going to fit the wide variety of body shapes exhibited by pilots then they had to ‘ban the average’ and instead ‘design to the edges’. It turned out that there were no ‘average pilots’ to design for in the first place! Rather, people exhibited ‘jagged body profiles’, or an uneven distribution of exceptional traits (i.e. height, shoulder width, hips, etc.).

Similar to the various body shapes of pilots, learners have similar variations within their individual learning capabilities. Someone with weak reading skills may understand the story better if they listen to it as they read along. For example, a screen reader can vocalize the text as the reader follows along in the text. On the other hand, a strong reader may have weak comprehension skills and hearing the story would not help their understanding or increase their ability to understand. Just like having options to adjust the pilot’s seat in a jet, similar options to adjust the learning task or environment can benefit a wider range of learners. Making the text suit an ‘average’ reader creates limitations and would not benefit either of the learners mentioned above. These barriers to learning may help explain lower levels of engagement in learners.

BIG Q: Who is Unheard?

There is a deep inflexibility in our education system because our ‘one-size-fits-all’ model is tuned to an industrial economic model that simply no longer exists in a global economy. Our evaluation practices incentivize top grades which result in schools competing against each other instead of fostering collaborative learning practices. This is often referred to as ‘teaching to the test’ and handcuffs the educator from being able to adopt or maintain effective pedagogical practices with consistency. This expectation of pedagogical consistency is precisely why teachers are a professional class. Nevertheless, students are encouraged to care about the finished product instead of the learning process itself. Long-term knowledge transfer suffers as a result and the curriculum is forgotten as soon as the test is over.

There is a deep inflexibility in our education system because our ‘one-size-fits-all’ model is tuned to an industrial economic model that simply no longer exists in a global economy. Our evaluation practices incentivize top grades which result in schools competing against each other instead of fostering collaborative learning practices. This is often referred to as ‘teaching to the test’ and handcuffs the educator from being able to adopt or maintain effective pedagogical practices with consistency. This expectation of pedagogical consistency is precisely why teachers are a professional class. Nevertheless, students are encouraged to care about the finished product instead of the learning process itself. Long-term knowledge transfer suffers as a result and the curriculum is forgotten as soon as the test is over.

The inflexibility baked into the system also means that everyone was forced to confront gaps in digital literacy and access to digital devices as we were launched into remote learning situations. Schools have the technology and we seem comfortable with it in personal social applications. However, some advancement needs to occur as we master optimal technology use in learning.

BIG Q: Are we Connected?

A new challenge to digital literacy lies in the difficulty of telling true information apart from falsehoods. Increasingly, social media platforms manipulate our emotions in order to engage our attention – in what is widely described as the ‘attention economy’ – with reckless abandon for the truth and the mental health of its younger users. How have pedagogical practices adapted to this new phenomenon? When a technology becomes rapidly normalized, questions about its long-term effects are rarely asked by its users. The potential harms of Instagram, for instance, may never reach the ears of its users. It is easy to see the benefits of connecting with a community that shares your values. However, as digital technologies and social media govern more of our time, we want to be intentional about the vocabulary we adopt and how we use these platforms. Something as simple as building-in mental or physical health breaks can improve our relationship with each other and with the technology that we use on a regular basis.

The role of parents and guardians was also an important factor in these new remote learning situations as they often had to directly support their child’s education. While some community school models had already integrated parental input into their educational programs, others may not have had such visibility into the home lives of their students. The shift to remote learning multiplied stressors on academic performance, from limited access to devices and internet, to food scarcity, to the inability of well-meaning working parents to be physically present to support remote learning environments, especially in single-parent households. These stressors have always existed, to one degree or another, but now they cannot be ignored.

Many students who were previously difficult to reach in a classroom were left to their own devices (pun intended). We were struck by a metaphor used by Shelley Moore to describe what can happen in a learning environment when a teacher is faced with a wide range of student needs and abilities. She described the urge to “aim for the middle” when bowling but cautioned that this approach often leads to a ‘7-10 split’. In bowling, this is the hardest shot in the game and no professional is likely to succeed when faced with it.

In teaching, a ‘7-10 split’ is like a lesson plan where all the students who need support and all those who need a challenge are left by the wayside of the lesson, creating an impossible situation for the educator. The moral of Shelley’s story is that you are more likely to help out all students by ‘designing for the edges’ rather than the most receptive or conspicuous students. The more inclusive your lesson, the more students it will affect and the more it will ripple through the class as a whole.

BIG Q: What’s Next?

Structures, practices, and expectations can stand in the way of physical, mental, or emotional well-being. We looked at obstacles that may hinder the well-being of students and teachers alike. All these areas impact each other which can make it difficult to distinguish them separately. Still, categorization can help clarify an issue by giving us neat ‘boxes’ to organize our perspectives. When we see what stands in the way of a healthy learning environment, it is easier to tackle the issues one by one.

Here are a few stressors:

-

- Physical:

- Lack of mobility for students and teachers.

- Tethered to technology means too much sitting.

- Activity is an afterthought and is sporadic.

- Emotional:

- Stressful evaluation procedures and expectations.

- Lack of equity & representation.

- Psychological:

- Lack of individual quiet spaces.

- Lack of time to explore, wander, or be curious.

- ‘Play’ is confined to recess.

- Physical:

We won’t suggest particular solutions to these challenges. What’s next depends on you, your colleagues, your students, and other affected stakeholders.

By the end of our discussion with Homa & Will, the BIG questions they posed to stimulate discussion encouraged us to dream of a better future for education together. We also look forward to the results of the research project led by Dr. Alain Breuleux. In the meantime, we hope you can also explore these questions within your learning environment. While we may be off the beaten path, together we can find our footing.

If you want to go fast, go alone; If you want to go far, go together.

– Unknown author

References

Lane, J., Therriault, D., Dupuis, A., Gosselin, P., Smith, J., Saliha, Z., Roy, M., Roberge, P., Drapeau, M., Morin, P., Berrigan, F., Thibault, I. & Dufour, M. (2021). The impact of the covid-19 pandemic on the anxiety of adolescents in Québec. Child Youth Care Forum. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09655-9.

Tavangar, H. & Richardson, W. (2021). 9 big questions schools must answer to avoid going “back to normal”. BigQuestions.Institute. https://bigquestions.institute.

Theodorus, A. (2019). The jagged edge of education. Binus University. https://student-activity.binus.ac.id/tfi/2019/08/the-jagged-edge-of-education/.

Interesting blog. Well done. My only comment is that you do not address the question of “what is learning?”. This is a question I have asked many times to countless educators who struggle to provide a cogent reply. Here is the definition I like best but which is rarely used or understood by many educators as it moves beyond knowledge acquisition (and testing) and focuses on learning assimilation. “Learning is “a process that leads to change, which occurs as a result of experience and increases the potential for improved performance and future learning” (Ambrose et al, 2010, p.3). The change in the learner may happen at the level of knowledge, attitude or behaviour. As a result of learning, learners come to see concepts, ideas, and/or the world differently.”